This page provides guidance to support all SLTs in their roles as practice educators, placement co-ordinators, service managers and staff at HEIs to provide high quality practice-based learning experiences.

Find out more about this guidance and view the glossary and acronym page.

Please contact us if you have any suggestions or feedback on these pages.

Last updated: October 2025

Back to practice based learning

Key messages

Provision of practice placements

- A commitment to practice-based learning should be included in all job descriptions and demonstrated by all SLTs at annual appraisal and through reflection and supervision processes.

- No speech and language therapy setting is considered too specialist to support practice-based learning.

- SLTs at all bands of the profession (or equivalent), including leadership and managerial roles, should be involved in practice-based learning. Band 5 SLTs may be involved in practice placements but should not take full responsibility for learner assessment until they have after gained their NQP competencies. SLT Assistants can support practice placements as part of a wider team.

- Peer placements should be provided where possible.

- Learners on apprenticeship programmes need access to the same practice placement opportunities (clinically based and non-clinically based) as those on traditional HEI based SLT programmes. This needs to be accounted for outside of work with their current employer.

Practice-based learning hours

Time on practice placements is counted in hours, rather than the previously used sessions, and will be operationalised in days (7.5 hours)/half days (3.75 hours) as fits with HEI timetables.

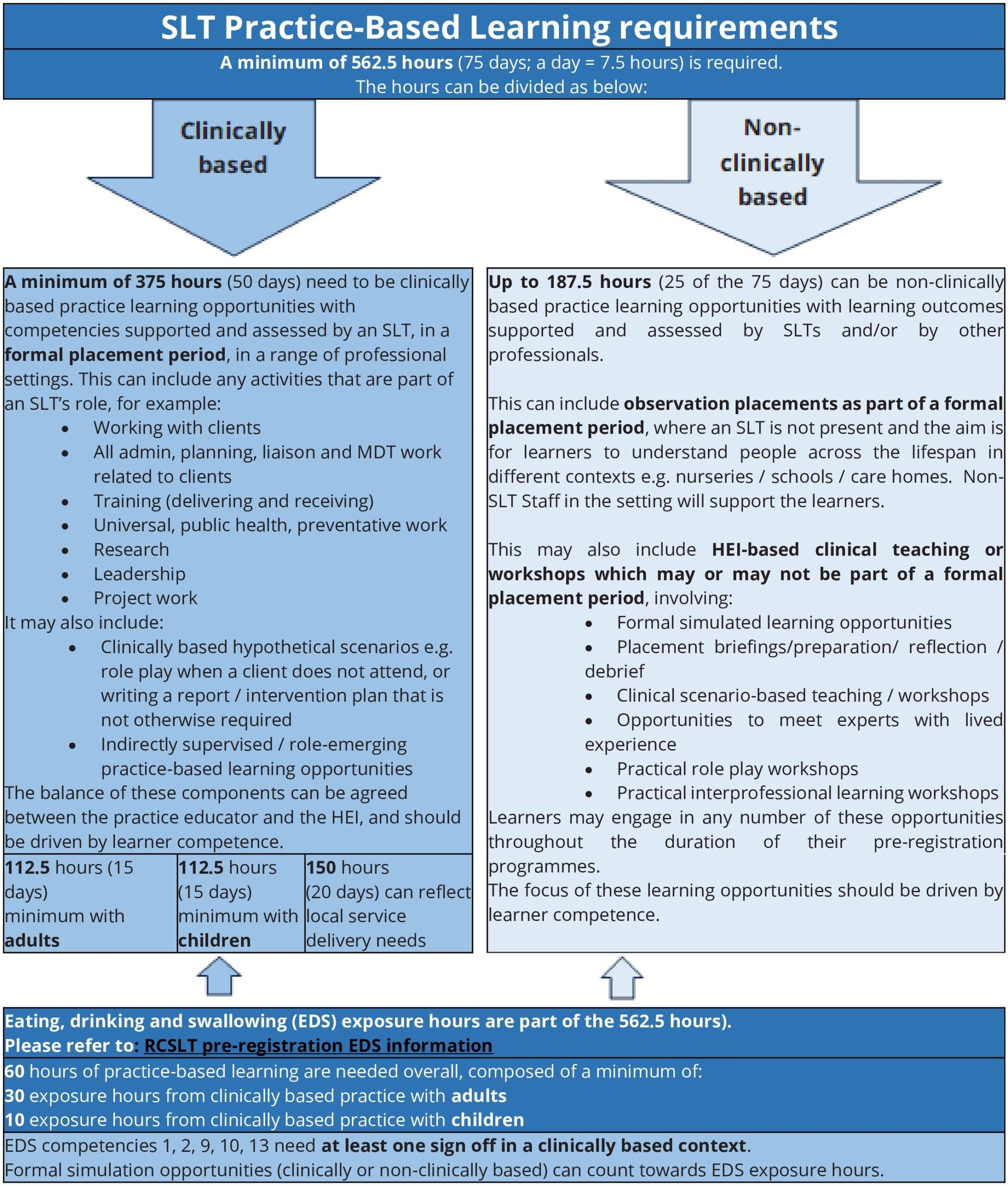

Learners need to complete a minimum of 562.5 hours (75 days) of practice placement opportunities across the duration of their pre-registration training.

The hours are split into the following components (as listed in the practice-based learning requirements infographic):

- 375 hours (50 days) of clinically based practice placement with competencies supported and assessed by SLTs as part of a formal placement period; the SLT does not need to be present with the learner at all times.

- 187.5 hours (25 days) of non-clinically based practice placement with competencies which can be supported and assessed by SLTS and/or by other professionals. These may be as observation days as part of a formal placement period in settings where an SLT is not present, or may be part of HEI based learning, not in a formal placement period.

- Of the 375 hours (50 days) of clinically based training:

- – a minimum of 112.5 hours (15 days) should be with children

- – a minimum of 112.5 hours (15 days) should be with adults

- – the remaining 150 hours (20 days) can reflect local service delivery needs.

Eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) practice-based learning hours are recommended by RCSLT and can draw from clinically or non-clinically based training. For apprentices, this is recommended outside of work with their current employer.

- 60 hours of practice-based learning in EDS is recommended in total for each learner

- 30 hours are recommended relating to clinically based EDS work with adults

- 10 hours are recommended relating to clinically based EDS work with children

- The remaining 20 hours can be acquired in HEI based workshops

- Non-clinically based formal simulation opportunities can count towards EDS recommended hours

Learners need to provide evidence of 16/20 EDS competencies, with double verification by the practice educator or the HEI. Some EDS competencies need at least one verification in clinically based sessions.

Quality practice placements

Equality, diversity, inclusion and belonging must be at the forefront of all of work with learners on practice placements, and this should be an integral component of practice educator training.

Practice placements should always be in supportive contexts for SLT learners. Practice-based learning provision evolves through a collaborative partnership between the practice education setting and the HEI. Practice educators need to demonstrate, teach and coach learners to develop clinical skills. Practice educators’ role in teaching clinical skills sits alongside assessing learner competence.

Processes to raise concerns, where learners do not feel supported, must be made explicit by HEIs and practice placement providers.

HEIs should provide link lecturers to each NHS trust/service that supports practice placements; this will facilitate the development and sustainability of practice placements.

Practice educators should attend educator training every 3 years.

Practice placements should be quality assured through transparent evaluation processes and practice placement settings should be audited every 2 years.

This guidance should be read in conjunction with the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework 2025 which sets out the roles and responsibilities of those involved in practice-based learning, including the learners themselves.

SLT Practice-based learning requirements infographic (jpg)

Background to SLT practice-based learning

Purpose of practice-based learning

Practice-based learning is a fundamental and indispensable element of training to become an SLT. It is the application of knowledge and skills, with service users and carers, in clinical learning environments. Practice-based learning provides the opportunity for learners to:

- apply theoretical knowledge in client-centred contexts

- develop clinical awareness and understanding

- learn and practice interpersonal and therapeutic skills

- embed the critical skills of reflection and self-evaluation in their learning and future practice, to enable them to work effectively with both service users and colleagues.

Breadth of practice-based learning

Practice placements provide experience of related health, social and educational provision for people with communication and eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties, as well as consideration of wider organisational and management perspectives. The provision of a range of practice placement opportunities, during speech and language therapy training, is therefore a crucial element in the development of competent clinicians, who are prepared for the workplace.

Regulation of practice-based learning

The Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) is the regulatory body which approves speech and language therapy pre-registration courses, and as part of this, assesses HEI systems and processes for acquiring and quality assuring practice-based learning opportunities. HCPC scrutinise the timing, length and assessment of practice-based learning, as well as the level of training and support for practice educators, against the HCPC Standards of Education and Training (2017) and the HCPC Standards of Proficiency (2023). Practice placement providers should adhere to these guidelines to meet the HCPC requirements.

Removal of the direct/indirect parameter for practice-based learning

Some measures were introduced to support practice-based learning provision during the COVID-19 pandemic e.g. a requirement for placements to consist of a minimum of 25% of direct client-facing work. As services have returned to more regular patterns of provision, this parameter has been removed, and it is recognised that practice placements can include any elements that are part of an SLT’s role. Practice placements should reflect the level of client work undertaken by SLTs in practice and can include a range of activities as illustrated in the infographic. The balance of these activities can be agreed between the practice educator and the HEI and should be driven by learner competence.

The removal of reference to direct and indirect practice-based learning opportunities is currently preferred, as this reflects the value of all clinical activities that are part of an SLT’s role. There is recognition that learners need time with clients on practice placements to develop their clinical skills, and it is the responsibility of the HEI to ensure that learners have this opportunity across the variety of practice placements that they access as part of their pre-registration programme.

The benefits of practice-based learning

There are clearly evidenced benefits of practice-based learning, other than to the learner and the HEI (Sokkar et al., 2019):

For the service user:

- Learners can share new ideas and up-to-date evidence-informed approaches that improve patient care

- Practice placements can support increased dosage of intervention for clients (both in NHS and in independent practice) leading to better outcomes and attainment of client goals

- Service users frequently report that they want to ‘give something back’, and value their role in the education of learners.

For the practice educator:

- Supporting learners is an important way for SLTs to demonstrate their continuing professional development (CPD)

- SLTs develop their leadership skills through working with learners, increasing opportunities for their own progression

- SLTs develop their clinical teaching skills

- SLTs develop their reflective practice skills, alongside learners

- SLTs can access cutting edge research and teaching via learners, and stay up to date in their own practice

- Supporting practice placements can enhance service delivery e.g. a learner can engage in information gathering with one client whilst the SLT works with another client

- Engaging in practice-based learning enhances workforce capacity to support additional and different service delivery models e.g. groups, increased therapy sessions, training programmes

- Learners can be given time to complete projects e.g. literature reviews, making resources, developing podcasts, completing audits, supporting waiting list initiatives; these are all activities which enhance service delivery and provide valuable learning

- Learners may be able to support some of the speech and language therapy work that cannot always be prioritised by SLTs; this can be factored into workforce planning.

For the speech and language therapy service:

- Engaging in practice-based learning can support recruitment; learners value practice placement experience highly and there is evidence to show that it influences their career choices regarding both the clinical practice area, geographical location and the organisation in which they choose to work (Jones-Berry, 2018). The national picture highlights some difficulty in recruitment to band 5 posts in certain areas; increasing learner practice placements in these areas will support this.

- Learners can support service improvement initiatives; can increase service delivery and can be an additional resource to develop new areas of practice.

- Regularly involving learners in client care aligns with the clinical governance agenda – providing practice placements is a way to support quality and enhance client care in a compassionate way.

- Demonstrating a regular and sustained commitment to practice-based learning promotes an ethos of dynamic service development and organisational learning.

- Learners may offer to volunteer for the service following a positive practice placement opportunity. This is not part of practice-based learning and would not attract tariff. Volunteers would not be supervised by the HEI.

Practice placement national organisation and allocation

The approach to practice placement organisation and allocation is currently different across the 4 nations of the UK.

All UK nations

- The expectation of the RCSLT is that every SLT should provide a minimum of 25 days per year per wte (pro rata), unless an explanation with a clear rationale can be provided. This recommendation applies across the UK, except in Northern Ireland, where specific central arrangements for placement allocation are in place. Learners are our current workplace colleagues and will form the future speech and language therapy workforce. Every practicing SLT has a duty to engage in providing clinical learning opportunities to support, inspire and enable learners to serve our clients in the best way they can, and to future-proof our profession.

- The issue of securing sufficient practice-based learning opportunities for all speech and language therapy learners is longstanding, and ongoing innovation in the development of practice placement opportunities is still required. A commitment to practice-based learning should be included in all job descriptions and demonstrated by all SLTs at annual appraisal and through reflection and supervision processes. This aligns with the Facilitation of Learning domain of the RCSLT Professional development framework.

- No speech and language therapy setting is considered too specialist to support practice-based learning. Practice placements can include any elements that are part of an SLT’s role, including all client focussed work, training, research, leadership and project work. The balance of these components can be agreed between the practice educator and the HEI and should be driven by learner competence development; there is no minimum requirement for any element, and a mixture is encouraged.

- SLTs at all bands (or equivalent) of the profession including leadership and managerial roles, should be involved in practice-based learning. This aligns with the Facilitation of Learning domain of the RCSLT Professional development framework. Band 5 SLTs may be involved in practice placements but should not take full responsibility for learner assessment until they have after gained their NQP competencies. SLT Assistants can support practice placements as part of a wider team but should not be responsible for learner assessment.

- Learners should not source their own practice placements, unless recommended by the HEI, as this can reduce parity and objectivity.

- Learners should not normally have practice-based learning opportunities in clinical environments where they are currently working e.g. as an SLT assistant, or where they have secured future employment, as this can cause potential conflicts of interest. Where this is unavoidable, any conflicts of interest will be addressed between practice educators, service managers and the HEI. If a learner gains employment in an organisation whilst they are on a practice placement in the setting, this will not usually cause any difficulties; any potential conflicts of interest need to be discussed between the practice educator, service manager and the HEI. There are other potentially conflicting situations e.g. where a learner has previously worked in a setting, in a non-SLT capacity i.e. as a teacher, or where they currently hold positions of responsibility or that may warrant a conflict of interest i.e. school governor, parent of children in a setting; these will need to be considered on an individual basis between the setting and the HEI, and an agreeable solution for all parties needs to be reached.

- Practice placement providers will deliver on all allocations/offers, and provide alternatives when allocations/offers are retracted, where possible.

- Practice placement allocations/offers in an area should be overt and transparent. They may be discussed at HEI meetings, local managers groups and ASLTIP forums.

- The geographical areas from which HEIs will seek practice placements are broadly defined by NHS Integrated Care Board/NHS Trust boundaries. The footprint for this is agreed between all of the HEIS and is available from any of the HEIs to share if requested. Even though the opportunity for telehealth placements does not restrict geographical distance for placements, HEIs will maintain the principle of seeking practice placements from their own area/locality.

- Placement providers should link with and prioritise their closest HEIs before offering capacity to other (out of area) programmes. Where an SLT practices (NHS or independent) working remotely, seek to link with an HEI that is not their closest geographically, there should be discussion and collaboration between the relevant HEIs.

- Where HEIs seek practice placements (onsite or via telehealth) outside their own area, they should contact the HEI in the area of the provider to discuss this collaboratively.

- Where there is a collection of HEIs offering speech and language therapy programmes in a neighbouring geographical area, a collaborative working model is encouraged to:

- prevent unhelpful competition in securing practice placements in the same geographical area

- share systems of planning, allocation and placement documentation where possible

- share clinical educator training for educators from both/all HEIs

- promote innovative practice in clinical education.

- Where HEIs are setting up new speech and language therapy courses, the expectation of the RCSLT is that they will demonstrate increased practice placement capacity.

England

- Speech and language therapy education in England is provided by a range of universities (HEIs) at undergraduate and postgraduate level. There is no direct commissioning of places from the Department of Health.

- HEIs currently work in collaboration with NHS England (NHSE) at a national and regional level. This may change with the Government abolition of NHSE across 2025 – 2027.

- The NHS Education Contract (2021) is an agreement between NHS service providers and the relevant local higher education establishments. It offers a framework for the delivery of practice-based learning and teaching to support workforce development. It clarifies responsibilities between the HEIs and all local service providers (including NHS, independent, voluntary and social care sectors).

- HEIs work in partnership with practice placement providers within their area to support and secure sufficient practice placement capacity. A variety of models between HEIs and placement providers are used e.g. allocation models based on SLT workforce capacity data, models requesting practice placement offers from local SLT services.

- It is recommended that services and HEIs use electronic platforms for offers and allocations e.g. Placement Management Programme (PMP), InPlace, PARE, ARC.

- Offers/allocations from practice placement providers are requested/shared on an annual basis (generally).

- Confirmations of practice placements should be done in a timely way; ideally one month in advance of the practice placement starting, where possible.

Scotland

- Since 2010, there have been AHP Practice-based learning Partnership Agreements in place between each Scottish university that runs pre-registration AHP programmes and each NHS Board. These were previously known as Practice Placement Agreements (PPA). These clarify an on-going commitment from each Scottish health board to provide a certain minimum amount of practice-based learning provision per profession each year. Each health board has an AHP Practice Placement group led by a Practice Education Lead.

- Each Practice-based learning Partnership Agreement has a stakeholder partnership statement, a generic agreement for all AHP groups and all organisations, and a schedule with profession specific details including the number of practice-based learning weeks that should be provided annually. NES facilitates the review of the Practice-based learning Partnership Agreements between the HEIs and practice placement providers, at regular intervals to incorporate any policy changes and to consider changes to numbers of practice placements required.

- The agreement contains details of agreed mandatory training prior to practice placements and a robust cancellation policy.

- Each HEI has links with SLTs practising in the independent and voluntary sector and these are arranged on an individual basis each year. The vast majority of clinical practice placements are provided in the NHS.

Wales

- Health Education and Information Wales (HEIW) currently commissions health funded training and bursary places for Speech and Language Therapy learners at Cardiff Metropolitan University and Wrexham Glyndwr University.

- A tripartite agreement re practice placement provision exists between HEIW, Welsh Health Boards and the HEI.

- Practice placements are commissioned across seven health boards. Each Health Board has a local level agreement with the HEI, which agrees the provision and support of clinical practice placements in their region.

- A profession specific practice education facilitator (PEFs) is employed in each board. These posts are held by SLTs. They are based within Health Boards and are funded by HEIW. The PEFs are employed by the NHS for a small portion of the working week to support quality assurance of practice placements. SLT training in Wales is fees funded, with agreement to work in Wales for 2 years post qualification. Practice placements are mostly provided by the NHS SLT Teams and are sourced and supported by the PEFs. Additional non-NHS practice placements may also be used for practice-based learning, with a clinical practice placement agreement in place.

- Commissioners fund travel and accommodation for learners on practice placement (means tested). Some practice placements require Welsh speaking learners to meet the needs of the specific population.

- Practice placements are organised and allocated centrally by the Clinical Director at the HEI, in collaboration with the PEFs, and the Health Board/non-NHS practice placement provider.

Northern Ireland

- Five Health and Social Care (HSC) trusts establish the parameters for practice placement provision for learners at Ulster University.

- Tuition fees are paid. The fees are paid by the Department of Health for all Northern Ireland learners that have been resident in the country for 3 years prior to the course commencing and students from the Republic of Ireland (excluding England, Scotland, Wales and the EU).

- A tripartite agreement exists between trusts, the HEI and the Department of Health. A practice education partnership committee safeguards best take up of practice placements. Practice placements are requested on a yearly basis and trust offers are guided by the number of learners needing to be placed and the relative size of each trust.

- It is expected that all practice-based settings should provide placements. All practice placements are based in the HSC trusts.

Practice placement provision as CPD

RCSLT supports a culture of continuous learning and improvement in the profession. This is enabled through continuing professional development (CPD) for all practising SLTs, and in the provision, planning and support for the future workforce. This aligns with the Facilitation of Learning domain of the RCSLT Professional development framework.

The education of future members of the speech and language therapy workforce is a joint responsibility, shared between speech and language therapy service providers and HEIs. Support for practice placements is required to ensure the sustainability and growth of the profession. As qualified SLTs, we all benefited from practice placement experiences as learners, and it is essential that all SLTs now support practice placement opportunities for current learners, where viable, to ensure the survival of our profession.

Commitment to practice placements and support for the future workforce should be written into job descriptions, and accounted for at annual appraisal, through reflection and supervision processes. Time to support the future workforce should be ring-fenced both for placement co-ordinators and practice educators.

RCSLT expectations of all SLTs

The expectation of the RCSLT is that all practising SLTs have a responsibility to engage in practice-based learning, irrespective of setting or banding. It is an integral part of the role of an SLT and is paramount to the future of our profession. The presence of learner SLTs in all clinical settings needs to be considered the norm, not the exception (Gascoigne & Parker, 2010). All new services, service initiatives and independent practices being developed should include plans as standard, with consideration of how learner-delivered services will extend or enhance the offering. Speech and language therapy services should view learners as assets, creating successful learning opportunities and enhancing service delivery for clients, for instance:

- enabling SLTs to offer group therapy

- providing additional therapy practice for clients

- preparing resources

- consulting the evidence base

A learner can be an integral member of any team, adding value, bringing new skills and sharing knowledge from cutting-edge teaching.

RCSLT calls on all SLTs to share the responsibility for our future colleagues and to provide a minimum of 25 days of practice-based learning, per year, per whole time equivalent (pro rata). This recommendation applies across the UK, except in Northern Ireland, where specific central arrangements for practice placement allocation are in place. The figure of 25 days placement provision per wte SLT was agreed, following national public consultation in 2021. This figure is broadly based on calculations derived from the number of practice placement hours required (375 clinically based), the number of learners in an HEI and the number of SLTs eligible to provide practice placements in the locality. If the provision of 25 days is not required by an HEI, they will inform local providers of their target figure.

Exceptions to the provision of practice-based learning

Situations which are exceptions to the provision of 25 days of practice-based learning might include:

- where an SLT is new in post (i.e. for the first 6-12 months)

- where services are managing significant numbers of vacancies or maternity/sick leaves and are on a risk register

- where clients do not consent to being seen by a learner

- where it is not financially viable; although RCSLT expects demonstration of a commitment to SLT learners in other ways, if the full 25 day provision is not possible.

Which SLT bands should support practice placements?

SLTs at all bands (or equivalent) of the profession including leadership and managerial roles, and band 5 SLTs should be involved in practice-based learning. This aligns with the Facilitation of Learning domain of the RCSLT Professional development framework. SLT Assistants can support practice placements as part of a wider team.

Band 5 (or equivalent) SLTs working towards NQP competencies are encouraged and are ideally placed to contribute to learner practice-based learning through supporting learner’s learning through:

- observations

- placement induction

- engaging in presentations and tutorials with learners

alongside more experienced SLT colleagues; they should not take full responsibility for assessing and monitoring a learner on practice placement. They are asked to focus on their own development until they have gained their competencies and can then engage fully with learner practice placements and provide 25 days (pro rata).

SLT leaders and managers (Band 7 and 8) may not hold clinical caseloads but are also expected to support SLT learners. Healthcare providers and educators need to facilitate leadership development in learners from the very beginning of their healthcare careers. RCSLT headquarters are now hosting practice placements to give learners insight into the working of the professional body.

To gain varied experience, as part of their practice placement, learners can also spend time with:

- SLT Assistants (SLTAs)

- colleagues from other health, education and care professions.

SLTAs can attend practice educator training and can support learners in skill development and practice. They can contribute to discussions about learner development and support observation placement days but should not have responsibility for verification of learner competence.

Which clinical settings should support practice placements?

No speech and language therapy setting is considered too specialist to support practice-based learning. Practice placements can include any elements that are part of an SLT’s role and can reflect the four pillars of practice: professional clinical practice, facilitation of learning, leadership and evidence, research and development.

The balance of these components can be agreed between the practice educator and the HEI and should be driven by learner competence development; there is no minimum requirement for any element and a mixture is encouraged. All areas of speech and language therapy practice should provide practice placements to all years of learners. Discussion may take place between HEIs and practice educators to match learner cohorts with practice placement provision. There are no SLT roles that are considered too specialist, too complex, or too confidential, to support learner learning. There is no gradation in the requirements for client confidentiality. For highly specialist areas of speech and language therapy practice, such as medico-legal work, SLTs can break down tasks and learners can complete specific elements of client-centred care e.g. completing a literature review to support the effectiveness and dosage of a recommended intervention, for a medico-legal report. Practice settings can work with HEIs to discuss how competencies can be addressed in certain specialist settings.

Expectations of practice placement supervision

Practice placement supervision needs to be structured so that learners feel supported, trained and coached to develop their clinical skills. Supervision should be tailored to the individual student, accounting for their learning preference. There should be clear aims for the placement and agreed learning outcomes that reflect learner development across the placement. Practice educators should provide regular and supportive feedback to learners. There should be opportunities to observe the educator, and the educator should provide overt explanation of their own clinical skills and application of theoretical knowledge. Learners should be scaffolded, coached and gradually supported in their clinical skill development. There should be clear pre-brief and de-briefs to give learners confidence in their clinical skill development. There should be opportunities for practice educators to observe learners too, and supportive feedback should be provided with strengths and areas for development clearly identified. Practice educators need to indicate learner competence in a context of a supportive teaching and learning environment.

Indirect supervision on practice placements

The SLT commitment to providing 25 days of practice education sits within the clinically based, formal placement period (See SLT practice-based learning requirements infographic in section 2). The practice educator does not need to be present with the learner at all times; where appropriate, learners can work independently with clients or on projects or tasks. This will usually be supported by planning with their practice educator and with opportunity to debrief afterwards.

Learners on some practice placements may be indirectly supervised by SLTs who are not based or working in the clinical setting where the practice placement is hosted. The supervising practice educator will support the learner as needed to plan and prepare for the activities and will regularly debrief with the learner and monitor their progress. This may reflect the format of a role emerging placement, where a business case may be supported by the evidenced outcomes of having SLT learners in the clinical setting.

Learners on SLT apprenticeship programmes

Learners on apprenticeship programmes need the same access to practice placement opportunities (clinically based and non-clinically based) as those on traditional HEI based SLT programmes. This needs to be accounted for outside of work with their current employer.

Practice educator training

Frequency of practice educator training

Practice educator training is required before SLT educators take responsibility for a learner’s practice-based learning. HCPC Standards of Education and Training state that educators must be appropriately trained, and must have the relevant knowledge, skills and experience to support learners of practice placements (HCPC SETs).

All practice educators can attend free practice educator training. This should take the form of:

- initial training as new practice educators

- follow up training for all educators should be 3 yearly

Band 5 NQP SLTs are encouraged to support SLT learners via observation but should not have responsibility for formal supervision or assessment of the learner. They may wish to engage in practice educator training if they are supporting a practice placement but should not have responsibility for assessing other learners until they have gained all of their competencies.

SLT assistants can also complete practice educator training to enable them to best support SLT learners on practice placements and to develop their own skills in modelling, breaking down tasks and giving feedback. SLT support workers should not take full responsibility for an SLT learner on a practice placement, but can be an integral part of the team supporting practice placements.

Practice education and CPD

Time to attend training should be protected and prioritised by practice educators and the service and should be recognised as CPD. SLTs should commit to providing practice placements within a year after having attended training.

All trained practice educators should evidence yearly progression of practice education skills in annual appraisals, or through CPD, reflection and supervision. These may be evidenced by attendance at courses, e.g. Professional Development practice education resources

Practice educators can participate in self and peer evaluation to facilitate their personal development as clinical teachers. Being a practice educator requires the same skill set as being an SLT: goal setting with learners, planning how to achieve the goal, teaching the various components that lead to the goal, evaluating the steps towards the goal, giving feedback to the learner on their development. This mirrors our work with clients: breaking down complex tasks into component parts and supporting learners to achieve them.

Format of practice educator training

Practice educator training may take the form of AHP training (with and run by AHP colleagues) for some elements and should be speech and language therapy specific for others. Training may be delivered face to face or via distance learning.

Neighbouring HEIs may provide and share practice educator training for local clinicians supporting placements for learners from more than one HEI. Training may be HEI led or placement co-ordinator led with HEI Involvement.

Other sources to support practice educator training include National Clinical Education groups and conferences e.g. National Association of Educators in Practice (NAEP), or Clinical Education Research Journals e.g. Journal of Workplace Learning, Journal of Interprofessional Care.

Practice educator training in Scotland

In Scotland, NHS Education for Scotland (NES) have developed an online module on the TURAS platform, regarding AHP student supervision and this is supplemented by the HEI-specific training. HEIs provide AHP practice educator preparation and update sessions and co-ordinate these across Scotland. The universities work closely together to provide similar content at their practice educator sessions. Practice placement quality is monitored using the Quality Standards for Practice Placements (QSPP) (NES, 2008). The QSPP audit tool details a set of standards for all AHPs to monitor and improve their practice placements. There are separate sections for completion by the learner, Practice Educator, Placement Coordinator and Organisations – both HEI and NHS. Details of all practice education initiatives can be found on the NES website.

Content of practice educator training

Practice educator training should include:

- setting up a practice placement

- preparing to host a practice placement

- providing learning opportunities

- learning approaches

- giving feedback

- theory to practice

- equity, diversity and belonging on practice placements

- making reasonable adjustments on practice placements

- grading learners

This list is not exhaustive and individual HEIs may include other elements relevant to their course and context.

HEIs should include in-practice educator training where educators are encouraged to factor in time within the placement day for learners to write up notes, undertake reflections and complete planning, to support the wellbeing and work/life balance of all learners (not just where this is specified as part of a reasonable adjustment plan).

Supporting learners from under-represented groups

Training must include how to support learners from under-represented groups, and should highlight dealing with discrimination, racism and micro-aggressions. Training should promote inclusion and diversity and raise awareness with respect to unconscious bias. Training should also cover transparent and supportive processes for learners to raise concerns about micro-aggressions and bullying from practice educators, please see RCSLT bullying guidance.

Practice-based learning models

Practice–based learning models need to align with the HCPC Standards of Education and Training HCPC SETs.

Evolving practice-based learning models

As dynamic practitioners, members of RCSLT encourage and support practice-based learning opportunities that are aligned with changing models of care and speech and language therapy service delivery, role configuration and developments in practice. Opportunities for practice education should contribute to the profession’s responsiveness to the changing population, client and service delivery needs e.g. as transgender services develop, further opportunities for practice placements in this clinical area should also develop. Practice placements need to be available across the employment sector (public, independent and voluntary) to reflect new and emerging practice settings.

A range of practice placement models are available. HEIs and placement providers should consider the appropriacy of the placement type to the learner stage.

Practice placement types

Practice placements will take a variety of forms depending on the HEI, the structure of the programme and their timetabling. Practice placement types may include:

- Observation days – These may fit the non-clinically based component of practice-based learning, as they may be in settings such as nurseries, schools, care homes. Learners have the opportunity to meet people across the lifespan and experience typical development and typical ageing. Learners in these settings may not be supported by an SLT, but will have a non-SLT educator in the setting.

- Once or twice a week placement days for several weeks – Learners attend the same setting for regular days for a set number of weeks. This happens alongside teaching days at university.

- Block placements – Learners attend the placement setting for 4 or 5 days per week and are not attending university teaching alongside. Learners are immersed in the practice placement setting for several weeks.

Practice placement formats

- Practice education may involve ‘in person’ or remote/telehealth placements or a hybrid. Telehealth placements may be provided where both the client, the practice educator and the learner(s) are working from different places, including from home, and link remotely for practice-based learning placements. Please see RCSLT Telehealth placements guidance for specific information.

- Shared placements where a learner is supported by educators in different teams or services for different parts of the practice placement e.g. 2 days per week in one setting and 2 further days in a different setting. A lead educator should be selected to provide the main feedback to the learner.

- Client pathway placements where the learner follows a client journey e.g. from acute ward to rehabilitation centre or community setting and spends part of the practice placement in both settings.

- Interprofessional practice placements e.g. contexts where learners are with other AHP students and are supported by AHP practice educators e.g. SLT and OT learners shared between SLT and OT mentors in a special school. The literature supports models like this e.g. where learners are able to explain the rationale for their plans to other learners, this helps them to refine their own understanding and clinical thinking (Baxter, 2004).

Learner numbers

The need to support increasing numbers of learners on practice placement and to equip learners with a broader range of employability skills e.g. collaboration, teamwork, leadership endorses the development of multiple learner supervision models of practice education (Walker et al., 2013).

- RCSLT encourages all practice educators to provide paired (or peer) practice placements, where possible. This can be counted as double, in terms of educator provision, i.e. working with 2 learners for 2 full weeks equates to 20 days of an SLTs practice-based learning contribution.

- Group practice placements with 3 or more learners with one educator; the effectiveness of multiple learners to one educator is well documented (Martin et al., 2004, Lloyd et al., 2014) e.g. HEI clinics where practice educators can focus on the learners due to having small caseloads and reduced operational pressures.

- Multiple learner placements e.g. 4:1, 6:1, 8:1 are also encouraged i.e. 4 learners with one educator for part of the placement e.g. to complete a project or join group tutorials by the practice educator and/or the HEI.

Supervision models

- Face to face: traditional placement where the educator is in the same setting as the learner and can offer face to face regular coaching, modelling, feedback and advice.

- Remote supervision: where the practice placement is provided digitally or online. The educator, learner and client are not in the same setting at the same time. The educator offers a clear supervision framework with support for planning and debriefing via technology.

- Indirect supervision: where the practice educator does not work in the setting where the practice placement is provided. There is a non-SLT mentor in the setting. The practice educator will regularly plan and debrief with the learner(s) to support their learning and skill development. The learner will carry out sessions and activities independently. Learners value the autonomy of these placements (Sheepway et al., 2011) and they can demonstrate the positive outcomes of enhanced SLT provision e.g. by providing more regular therapy than is currently available.

- Role emerging placements: the practice educator does not work in the setting but supports the learners and the placement experience provides outcomes for a business case to seek funding for the SLT role in that setting.

- Peer mentoring i.e. final year learners supporting first year learners on observation practice placements.

Roles and responsibilities in relation to practice-based learning

Practice-based learning roles and responsibilities framework

Please see the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025) which indicates the key information about roles and responsibilities of learners (including apprentices), practice educators, placement co-ordinators, service managers, practice learning facilitators and HEIs in relation to practice-based learning.

Responsibilities of learners

In addition to the roles and responsibilities indicated in the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025):

- When the practice educator and the learner are both confident that the learner is competent to work with clients autonomously, learners should take opportunities to plan and deliver client-facing sessions independently. A graded approach towards this is key: supported by structured observation, modelling and coaching by the practice educator, and involving thorough planning and debrief sessions.

- Learners with reasonable adjustment plans are strongly encouraged to share plans to support their learning on practice placements with practice educators, so that they may benefit from additional support on practice placement.

- Learners on peer or group practice placements need to recognise their responsibility towards their peer(s), work co-operatively and collaboratively, and take shared responsibility for the activities in which they are jointly engaged.

Responsibilities of practice educators

In addition to the roles and responsibilities indicated in the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025):

- All UK practice educators will be HCPC registered SLTs.

- Where a learner has more than one educator in a practice placement setting, there should be a lead practice educator, identified to the HEI and the learner. This educator has the responsibility to co-ordinate feedback from other educators and to share the feedback and placement outcome with the learner.

- Additional liaison from the HEI may be required if educators span different services i.e. NHS and independent practice; there should be a lead educator in each service. Learner assessments may be completed separately but may complement each other and collaboration between educators is recommended. If a skill is not achieved in one setting by a learner, but is achieved in another, a discussion between educators and the HEI is recommended and a decision made re whether the learner can pass that competence.

- Practice educators should provide clear, supportive feedback for learners; ideally this should be written. Feedback should focus on strengths and areas for development. This is best practice throughout the placement and is essential at key points during the practice placement e.g. at mid–point, and at the end of the placement. Some HEIs have specific guidance as to the regularity of written feedback.

- On a peer or group practice placement (where there is more than one learner with one practice educator), practice educators should provide individual feedback to the learners.

- Learners on indirectly supervised or role emerging practice placements need educators to observe some of their clinical sessions to give clear and specific feedback to support the development of their clinical competence.

Responsibilities of placement co-ordinators

In addition to the roles and responsibilities indicated in the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025):

NB: This relates to settings where an SLT is allocated the role of placement co-ordinator within a service; for independent sole practitioners this will not be a differentiated role.

- Placement co-ordinators need protected time for this role as part of their job plans and have a key role in supporting staff to provide practice placements.

- They should ensure that all staff are aware of their roles and responsibilities in relation to learner education.

- They should have the opportunity to host a learner slot at staff meetings and have a pivotal role in liaising between the HEI and the clinical staff team, keeping information updated in both directions.

- In Wales, the profession specific Practice Education Facilitators (PEFS) undertake the role of placement coordinator.

- In Northern Ireland this role is not formalised.

Responsibilities of service managers

In addition to the roles and responsibilities indicated in the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025):

NB: For independent sole practitioners, this will not be a separate role.

- Service managers (public and private sector) have a responsibility to ensure all eligible SLTs provide 25 days of learner practice placements (pro rata), unless a rationale to opt out has been discussed with the HEI.

- Service managers are best placed to explore with teams who feel unable to provide their quota of learner practice placements, how they might support practice-based learning in other ways, to contribute to the development of the future workforce.

- Service managers, as part of their workforce planning, can ensure that learners are included and can support service delivery.

- Service managers in the NHS should ensure that Learning Development Agreements are in place at Trust level with the HEIs (in England).

Responsibilities of Practice Education Facilitators (PEF)/Practice Learning Facilitators (PLF)/Practice Education Leads (PEL)

This is an additional role related to practice-based learning which is aimed at practice placement quality monitoring for non-medical professionals.

- In England, PEFs are funded through NHS. The number of these posts in an organisation is determined by the Learning Development Agreement (LDA) and the number of learners. PEFs aim to lead on the development of practice learning opportunities in the service and work with the HEIs to co-design and review practice placements and support the development of practice educators.

- In Wales, there are a number of profession specific PEFs who support practice-based learning within Wales. They are based within health boards and are funded by Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW). They are employed by the NHS for a small portion of the working week to support with quality assurance and management of practice placements.

- In Scotland, a similar role is undertaken by Practice Education Leads in each health board funded by NHS Education Scotland (NES).

- In Northern Ireland each Trust has a practice education lead who works closely with the HEI and supports the management of practice placements. This role is funded non-recurrently in some Trusts and not funded at all in other Trusts.

Responsibilities of HEIs

In addition to the roles and responsibilities indicated in the RCSLT Practice-based learning Roles and Responsibilities Framework (2025):

- There should be transparency from the HEI re learner numbers recruited each year.

- HEI tutors and practice educators should liaise throughout the practice placement. The style of contact (email or onsite/remote visit) and timing will vary depending on the length of the practice placement.

- HEIs should contact practice educators at the midpoint of the practice placement to discuss the learner’s progress.

- There must be an agreed process in place between the HEI, the practice educator and the learner, where there are concerns about the learner’s progress. The aim is always to enable the learner to successfully complete the practice placement. The support will include a 3-way collaborative discussion between the HEI tutor, the learner and the practice educator, with clear written actions for all to take forwards, to work towards a positive outcome.

Requirements of practice-based learning

Practice placement hours requirements

RCSLT specifies that SLT learners need to complete 562.5 hours (75 days) of practice-based learning (RCSLT Curriculum Guidance 2025) over the duration (2, 3 or 4 years) of their pre-registration programme. This is the same for undergraduate and postgraduate routes, and for learners on apprenticeship programmes.

Practice-based learning requirements can be divided into two components to support competence development in clinically based formal placement periods and in non-clinically based activities. Please see the SLT practice-based learning requirements infographic in section 2 for an overview.

Rationale for current practice placement hours

Following in-depth consultation and discussion, RCSLT supports the view that 562.5 hours is sufficient to equip most current graduates to gain the competence required to meet the demands of band 5 NQP roles. Many HEIs include more than the minimum of 75 days of practice-based learning across the duration of their programmes.

Whilst it is noted that other AHP colleagues complete more practice placement sessions than SLTs, currently there is no clear evidence nor compelling argument that an increase in hours is needed for SLT placements. In SLT placements, the focus is on learner competence development and the quality of practice placements, rather than on quantity in terms of practice placement hours.

SLT pre-registration training needs to encompass both the speech, language and communication content as well as the eating, drinking and swallowing strand. Theoretical underpinnings in SLT include extensive components of linguistics, phonetics, behavioural sciences and psychological theory which are important to grasp, to be effective evidence-based clinicians. The diverse scope of SLT practice demands in-depth understanding of these theoretical domains to support skilled clinical reasoning. The SLT curriculum is heavily aligned to psychology, and the balance of HEI and practice placement learning aligns with the requirements of the SLT profession.

If RCSLT were to review the practice-based learning hours again in the future, there would need to be consideration towards extending the length of pre-registration programmes as there is so much content included in the curriculum. It would not be possible to extend placement hours within the current course timeframes without compromising learner well-being or academic integrity.

The 2024 informal survey comments from SLT services (managers, employers, SLTs, NQPs and placement co-ordinators) indicated that current practice placements are sufficient to enable NQP SLTs to join the workforce as long as regular, substantial and specific support to NQPs is provided, as per RCSLT NQP guidance in the first year of practice. This is further endorsed by the recently published Eating, Drinking and Swallowing guidance.

HEIs and practice placements need to offer support and preparation for the workplace to final year students, in terms of the practicalities of diary organisation, time management, making phone calls, writing case notes and reports. This can be supported through active meaningful learning using a range of different learning approaches, rather than reliance solely on placement hours.

Recording of practice placement hours

Practice placement requirements should be recorded in hours (rather than the previously used sessions). Conversion of these hours to days (based on a 7.5 hour full working day, as per most professional work environments) can be used by HEIs and settings to enable placement allocation and planning.

The rationale for this change is that hours are a consistent way to track practice-based learning time, they are less confusing than sessions (everyone knows what an hour is), and they are more accurate and objective. Recording practice placement activity in this format provides more flexibility for practice educators who work part time, and more equity for learners across different practice placements. Other AHPs use hours to record practice placements and the NHSE return for placement tariff (England only) requires recording in this way. The use of hours will allow easier alignment with the RCSLT EDS hours requirement. It was also considered that the use of hours will increase the responsibility of learners to be accountable for their practice-based learning hours.

The 375 hours of clinically based practice-based learning are equivalent to 50 days on the basis of a 7.5 hour working day (e.g. 9-5pm with a half hour lunch break). It is acknowledged that some educators do not work 7.5 hour days. If an educator works a 5 hour day, they can agree with the HEI that the learner completes an additional 2.5 hours of placement related work (with tangible agreed outputs) which then allows the learner to be signed off as having completed a full clinical day (7.5 hours). If an educator works longer than a 7.5 hour day, an agreement between the learner, the educator and the HEI is needed to decide on the length of the day for the learner. It is noted that NHS Scotland are moving to a 37 hour working week, before further reducing to a 36 hour working week.

The balance of clinical experiences must be provided for all learners over the duration of the programme and should be monitored by the HEI. For part time training routes, practice-based learning opportunities needs to match full time routes. Ideally, there will be a period of clinical practice close to the end of the degree programme so that learners have recent experience of practice placements when graduating.

HCPC guidance (2015) states that: “It is important to realise that learners do not need to be able to do all types of practice placement to be able to show they meet all of the standards of proficiency needed before they can register with us”. HEIs can operationalise this guidance, taking into account knowledge of the learner, and the possible practice placement opportunities. It can be appropriate to recognise that some clinical settings may challenge certain learners, and HEIs need to support learners accordingly. This may include the accommodation of reasonable adjustments in the setting in question, or the acquisition of competencies on other clinical settings if appropriate and available.

Where learners miss practice placement days, these should be made up in line with HEI requirements for attendance in practice placement.

Clinically based practice learning contexts

Of the 562.5 (75 days) of practice-based learning, learners need to complete a minimum of 375 hours (50 days) in clinically based practice-based learning contexts, as part of formal placement periods, and 187.5 hours (25 days) in non-clinically based practice-based learning activities.

The 375 hours (50 days) of clinically based practice-based learning will be supported and assessed by an SLT. This support can be face to face, remote or indirect (See Practice-based learning models, Supervision models section)

The 375 hours (50 days) will support learner competence development to meet the HCPC Standards of Proficiency (2023). They can include any elements that are part of an SLTs role, for example:

- working with clients

- all admin, planning, liaison and MDT work related to clients

- training (delivering and receiving)

- universal, public health and preventative work

- research

- leadership

- project work

And may also include:

- clinically based hypothetical scenarios e.g. role play when a client does not attend, or writing a report/intervention plan that is not otherwise required

- indirectly supervised/role-emerging practice-based learning opportunities

A proportion of the placement may be configured as dedicated study time (e.g. for preparation and planning) and this may count as clinically-based hours where there is an agreed tangible output to meet a specific learning outcome, at the discretion of the practice educator and the HEI.

The previous differentiation between direct and indirect clinical work has been removed from this guidance, as all elements of an SLT’s role can support learner competence development. The balance of these components can be agreed between the practice educator and the HEI and should be driven by learner competence development.

Practice placements need to cover the breadth of clinical areas, as below:

- 112.5 hours / 15 days with adults

- 112.5 hours / 15 days with children

- 150 hours / 20 days can reflect local service delivery needs

HEIs can use their discretion for recording placements in colleges that might span the 16-25 year age group, or for placements with adults with learning disabilities, as adult or paediatric hours, as they might be recorded from a chronological or a developmental perspective.

Non-clinically based practice learning contexts

Up to 187.5 hours (25 of the 75 days) of non-clinically based practice-based learning can include:

Observation placements as part of a formal placement period, where an SLT is not present and the aim is for learners to understand people across the lifespan in different contexts e.g. nurseries / schools / care homes. Non-SLT staff in the setting will support the learners.

This may also include HEI-based clinical teaching or workshops which may or may not be part of a formal placement period, involving:

- formal simulation learning opportunities

- placement briefings/preparation/reflection/debrief

- clinical scenario-based teaching/workshops

- opportunities to meet experts with lived experience

- practical role play workshops

- practical interprofessional learning workshops.

The focus of these sessions should be driven by learner competence development.

Detail and examples of some these sessions is below:

Clinical scenario-based teaching/workshops

Clinical scenarios could involve requests for assistance/triage decisions, end of episode of care decisions, or breaking bad news. Professional scenarios could involve caseload prioritisation, MDT working or legal and ethical issues. Clinical videos may be part of these sessions to enable learners to follow the service user journey from request for assistance to end of episode of care, engage in case history and information gathering discussions, complete assessments, plan and discuss interventions, and thus develop clinical decision-making skills.

Opportunities to meet experts with lived experience

These will involve real service users and carers who volunteer their time to support learner learning; e.g. share and discuss their experiences, provide repeat case history opportunities, repeat assessment experiences, repeat intervention practice, and are an additional source of feedback.

Practical role-play workshops

This will involve learners practising and developing clinical skills with educators/peers.

Practical interprofessional learning workshops

This will involve learners engaging in practical sessions with peers from other relevant professional courses e.g. nursing, other AHPs, social work, teacher training where they will learn about other professions and consider elements such as role boundaries, strategies to work in a joined up way to support client outcomes.

Eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) recommended exposure hours

EDS practice-based learning recommended hours should be embedded within the 562.5 practice-based learning hours. Please see the RCSLT pre-registration eating, drinking and swallowing competencies for more detail about the EDS competencies and verification on practice placements.

The EDS requirements involve 60 recommended exposure hours of EDS practice-based learning, composed of a minimum of:

- 30 hours recommended from clinically based practice with adults

- 10 hours recommended from clinically based practice with children

- the remaining 20 hours can be from HEI based workshops.

Non-clinically based formal simulation opportunities can count towards EDS practice-based learning hours.

There are 20 EDS competencies, of which 16 need to have double verification of evidence by the practice educator or the HEI. The evidence should be recorded by the student and should reflect experience of or exposure to the knowledge and skills covered in the 20 competencies. Five of the EDS competencies require at least one verification from an educator in clinically based sessions. There is no expectation of learner competence from these EDS exposure hours and all NQPS required to work with people with EDS, will need to complete the new RCSLT EDS competency framework (2025) with mandatory verification at Foundation level, before they commence any autonomous practice with clients with EDS.

Service user consent

Practice educators need to ensure that clients have consented to working with learners on practice placements.

Insurance for learners on practice placements

Learners on practice placements are covered under the RCSLT professional indemnity insurance policy, provided they are RCSLT student members. If the student is not a member, insurance must be provided by the HEI.

For SLTs in independent practice, the RCSLT policy includes employer’s liability cover for the duration of the placement, enabling qualified SLTs (including sole traders) to supervise students.

Failing practice placements

There are some learners who may not reach the required level of competence to pass each specific placement within the designated timeframe and therefore will need more than the minimum required 562.5 hours to successfully complete the pre-registration programme. Where a learner is not meeting the parameters to pass the placement, practice educators should contact HEIs and work together to support the learner as indicated. Where a learner fails a specific placement, they should be offered one (and only one) further practice placement opportunity for that specific placement period. It is hoped that with more time and experience, the learner will successfully complete the resit placement. Learners can have the opportunity for one resit practice placement for each specific failed placement.

Simulation as part of practice-based learning

Definition of simulation

Simulation is an immersive teaching methodology providing experiential learning opportunities, which is well established in healthcare education (Irvine & Martin, 2014). It offers the opportunity for learners to practice specific clinical skills and to focus on their own learning, with no impact on clients, in a safe learning environment (Alinier, 2007; Penman et al., 2020; Hewat et al., 2020). Simulation involves a structured framework with clearly intended learning outcomes, and formal pre-brief and de-brief elements to give clarity to the learning. Simulation should be facilitated by a trained clinical educator (Hill et al., 2020).

Types of simulated learning

There are a range of different ways to use simulation as part of practice-based learning. There are various levels of immersion in simulated placement environments such as:

- replica hospital wards

- replica clinics

- communication suites

- general university classrooms.

There is also a variety of simulated learning experiences (Hill et al., 2020) e.g.

- simulated patients where actors present as typical clients

- standardised learning opportunity where trained experts by experience are available for repeated learning opportunities

- learner role play opportunities

- video scenarios

- extended reality: virtual reality e.g. HoloLens and avatars, augmented reality and mixed reality

- and paper-based case scenarios.

Inter-professional learning opportunities lend themselves well to simulated practice-based learning scenarios too (Mills et al., 2019).

The advantages of simulated learning

In a climate with continual pressure on practice placements, simulation offers an equitable learning experience for all learners as part of their pre-registration speech and language therapy programmes. There are well documented advantages of simulated learning including:

- opportunity for skill repetition

- parity of experience for learners

- wider variety of clinical opportunities

- guaranteed exposure to experiences that might not be available on practice placements

- can offer more complex clinical contexts that learner might be shielded from on placement

- improved learner confidence via a safe learning opportunity

- offers a more overt learning experience

- feedback from a range of sources (facilitator, peer, simulated client)

- cost effectiveness.

(Alanazi et al., 2017; Hamada et al., 2020; Hill et al., 2020; Ker & Bradley, 2014; Ormerod & Mitchell, 2023)

Evidence of the effectiveness of simulated learning

Experiential learning through simulated clinical experience has a robust evidence base (Hamada et al., 2020); it has been demonstrated across nursing (Guimond & Salas, 2009), medicine (Irvine & Martin, 2014), and AHP practice education (Hill et al., 2020). Hayden et al. (2014) found that there were no significant differences in knowledge, clinical competency, critical thinking and readiness for practice in nursing learners where simulation substituted 25% and 50% of clinical placement time. Watson et al. (2012) also investigated learner outcomes when 25% of placement was replaced by simulation and noted no significant differences.

Through a randomised control trial carried out across six university speech pathology programmes in Australia, Hill et al. (2020) reported that speech pathology learners achieved a statistically equivalent level of competency when an average of 20% of their practice placement time was replaced with simulation-based learning, compared with learners without a simulation component.

In terms of the impact on clients when learners are trained via this methodology, Seaton et al. (2019) demonstrated that outcomes for patients are positively impacted by simulated learning experiences, and specific to Speech and Language Therapy, Penman et al. (2020) evidenced the effectiveness of a simulation approach which supported learner’s skill development in clinical practice with clients who stutter.

Recommended framework for best practice simulated learning experiences

It is recommended that a clear framework is used to support quality simulated learning experiences and that HEIs purchase simulation software to support this teaching methodology. RCSLT recommends adherence to the Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) Standards guiding simulation-based practice in health and care (2023).

The simulation-based learning program developed by Dr Anne Hill at the University of Queensland is one available resource. This programme includes learner workbooks, clinical educator workbooks, clinical educator training workbook, simulated patient training workbooks, simulation set up guides, and a series of simulated patient case studies.

Decker et al. (2008) state that the ideal ratio to support focussed learning is 6-8 learners in a group with one trained clinical educator. The complexity of the simulation experience should be tailored to the stage of learning of the learners.

The specific simulation framework needs to include:

- clearly differentiated pre-brief,

- simulated activities with feedback embedded from tutor, peers and simulated client

- formal de-brief where learner measures progress against learning outcomes

- self-reflection elements.

Pre-brief

This is a formal start to the simulation experience where intended learning outcomes are agreed with learners. It is important to clearly define the intended learning outcomes for each simulation to ensure the appropriate type of simulation is selected and aligns to the learner’s level of learning (Alinier, 2007).

Feedback as part of the simulation activity

There are two main methods of giving feedback during the simulation experience:

- In-session feedback

This does not interrupt the interaction with the simulated client, it is a form of offering brief support to the learner, from the educator or peer. It reflects what might happen in any practice-based learning session, with the learner leading an activity and the educator prompting or steering the interaction.

- Pause – discuss feedback

This does interrupt the learner-patient interaction. The simulated patient stays in role, the learner or educator may request a pause in the session. The learners and educator discuss what they have observed. This is useful to support clinical reasoning and skill development (Ward et al., 2015). This model can follow two formats:

- The learner requests a pause to seek assistance. The simulated patient may be involved in the discussion.

- Time in / Time out technique: here the pause is requested by the educator (Edwards & Rose, 2008). A ‘time out’ may be used to discuss what was observed, clinical reasoning and the learner’s performance. The opportunity is then provided to enable the learner to repeat the interaction, or try a different approach. ‘Time in’ is then called when the learner repeats the interaction. The cycle of pause and discuss can repeat.

Guidelines to learners for giving and receiving feedback are important, to support specificity, skill development, and to focus on strengths as well as areas that may change (Hill et al., 2020).

Debrief

There are a range of debriefing models that are important to apply; the debrief is where the learning takes place. Speech Pathology Australia (2024) include some of these models in their clinical educator training workbook. The framework includes a range of approaches including Stop, Keep, Start (Hoon, 2015), and appreciative enquiry (Hammond, 1998).

This approach to feedback is based on the assumption that in every situation something works and the following questions might be discussed in the debrief e.g. ‘what worked well?’, ‘what did you do that made it work well?’, ‘what contributed to this working well?’.

Reflection

Formal reflection needs to be embedded in the simulation process, this might be verbal or written, individual or in a group, and may be prompted by questions such as ‘what happened?’, ‘what did I do well?’, ‘what should I change for next time?’, ‘how do I feel about that situation?’, ‘why did I feel that?’, ‘how can I build on what learned?’. A formal reflective cycle e.g. Gibbs, Driscoll, Kolb may be used.

Table 1: An example framework (after Speech Pathology Australia, 2024)

| Process | Time | Activity | Resources |

| Pre-brief | 30 mins | Agree intended learning outcomes

Introduce learners to case Review documentation Workbook activities completed in groups Agree tasks |

Learner workbook

Documentation related to cased |

| Simulation | 60 mins | Learners work in pairs or individually

Feedback method agreed e.g. pause and discuss |

Resources for session e.g. assessment, therapy, goal setting discussion |

| Learner debrief with peers and practice educator | 60 mins | Debrief method

Learners complete activities in workbook |

|

| Learner reflection | Individual reflection | Reflective cycle |

Table 2: Example framework for a clinical simulation session based on aphasia therapy (after Speech Pathology Australia, 2024)

| Process | Time | Activity | Resources |

| Pre-brief | 30 mins | Agree intended learning outcomes: Implementing aphasia therapy

Introduce learners to case: Mr T Review documentation: previous case notes for Mr T Workbooks activities completed in groups: complete session plan Agree tasks: between learners

|

Learner workbook

Documentation related to case |

| Simulation | 60 mins | Learners work in pair or individually

Learners role play client (Mr T) and SLT Learners explain task to Mr T Adapt during session to reflect client’s needs Communicate next steps to client Feedback method agreed: ‘in session feedback’ method Pause and discuss options |

Resources for session e.g. assessment, therapy, goal setting discussion |

| Learner debrief with peers and practice educator | 60 mins | Debrief method: Stop-keep-start Appreciative enquiryLearners complete activities in workbook |

|

| Learner reflection | Learners write up own reflection following debrief | Reflective cycle |

Use of simulation as part of practice-based learning hours

Simulation is currently mostly used in the UK as a teaching methodology. It is often adopted as placement preparation experience. Formal simulation that meets ASPiH standards can be used as part of the 187.5 hours (25 days) non-clinically based practice-based learning opportunities. There is a growing evidence base that supports the use of formally developed simulated learning experiences (using a structured framework) as equivalent to practice-based learning (Hayden et al., 2014; Hill et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2012), and in time this may be agreed as a replacement for clinically based practice-based learning opportunities.

EDS simulation needs to be a key part of HEI based learning to ensure that learners can achieve their competencies and hours, so that they will be able to complete their EDS training, graduate and join the workforce.

There is also opportunity to use hypothetical learning opportunities as part of clinically based practice-based learning in formal placement periods, on an ad hoc basis e.g. if a client does not attend a clinical appointment and there is the opportunity to role play the session with the educator. These opportunities are part of the informal and multifaceted ways that practice educators support learners on practice placements. In England, the tariff (funded by NHS England and available only in England) will apply to simulation which replaces clinically based practice-based learning opportunities but will not be paid if simulation activity is delivered as part of the education provider’s teaching requirements.

Recording learner progress on practice placements

Passing placements

Practice placement grading can be PASS/FAIL or include a numerical grade, dependent upon the HEI requirements. Practice placement assessments are not standardised across HEIs and it is the responsibility of the HEI to quality assure practice placements, and to train practice educators in assessing student competence.

Practice educators should be familiar with the documentation of the HEI. Where HEIs are geographically close and regularly share practice areas, there should be collaboration between HEIs with respect to shared practice placement documentation to support efficiency and clarity for the educators.

Competency based assessments are welcomed and can identify exactly what competence the learner has achieved i.e. ‘gathers information, records accurate observations, and can assimilate and discuss information’ is preferable to a task list e.g. ‘can take a case history’ (McAllister et al., 2010).

Practice placement documentation should include: