RCSLT and speech and language therapy history

In 2020, the RCSLT celebrated its 75th anniversary. Jois Stansfield, emeritus professor at Manchester Metropolitan University, traces the development of the RCSLT from its founding in 1945 to the present day and explores key figures and moments in the profession’s history.

75 years of speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapy in the UK became organised under a single professional body in 1945 as the College of Speech Therapists, now the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, which is planning celebrations for its 75th anniversary in 2020.

Exploring the history of speech and language therapy gives us the opportunity to understand where we have come from and recognise how this influences our current and future professional lives.

I am currently conducting an oral history project, which has involved interviewing SLTs who qualified between 1945 and 1969. This has been eye-opening in terms of how the profession has changed in numbers (from just over 200 members in 1945 to the most recent figure of 17,422 members, indicated in the RCSLT’s 2018-19 Impact Report), but also in terms of the methods, challenges and opportunities reported by the participants.

Full analysis is at an early stage, but during the conversations, participants provided all sorts of pictures and artefacts that reflected their experiences of work across the years.

Professional identity

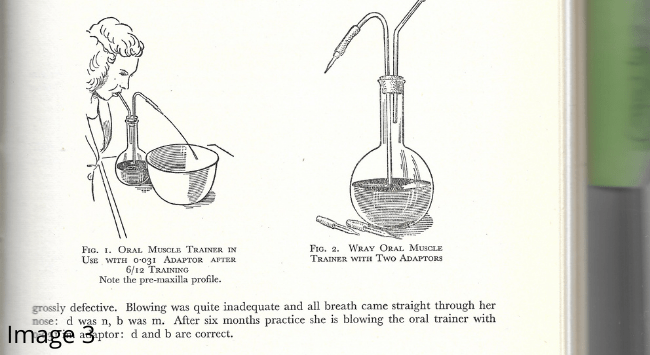

Speech and language therapy thrives on both real and stereotyped professional identity. In my interviews, ‘twinset and pearls’ were mentioned on numerous occasions, and one participant said that, while studying at college, student SLTs “had to wear blazers with the colours round it, and the proper scarf”.

There were many references to the professional and statutory bodies; logos and publications produced by these organisations were seen as defining the profession.

Other items included qualification ‘parchments’, Licentiateship of the College of Speech Therapist (LCST) badges (the original LCST badge had the member’s number on the back) and Communicating Quality (1991, 1996 and 2006). Academic life was represented by examination papers, journals, key text books and photographs of fellow students.

Innovation

In the 1950s there were no British standardised speech and language therapy assessments, and necessity was the mother of invention. One participant mentioned, for example, Joan van Thal’s invention of “a piece of apparatus which was a sort of jam jar for detecting nasal escape”.

The first standardised test to be published was probably the Coral Richards language test in the late 1960s, followed by the Renfrew Scales and the Reynell tests for children (which are still in use) and the Edinburgh Articulation Test.

Assessment of grammar was enhanced by the Language Assessment, Remediation and Screening Procedure (LARSP) in 1978, although many participants struggled with this at first because, as one said of their course in the 1950s, “we did phonetics, but linguistics wasn’t part of our curriculum”.

Adult assessment continued to use American materials, including the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination, with the ‘cookie theft’ picture being one element of the more detailed assessment.

People listed a range of therapy essentials. In the words of one participant, who qualified in the early 1950s, she had only “one of these little wicker baskets… and in it, a set of small hand mirrors and a package of straws”. Others mentioned “a bunch of keys to entertain kids” (or, more soberingly, “a bunch of keys to a locked hospital ward”), as well as ping pong balls for blowing exercises, popular games, reward stickers and specifically designed therapy tools.

There are still firm favourites that make a regular appearance in many clinics (Pop-up Pirate, anyone?), but technology has changed the way speech and language therapy is delivered, and people mentioned both old and new approaches.

Older members of the profession recalled recording devices that were too heavy to carry, and ‘eye pointing picture charts’.

In stammering work, the electronic metronome and Edinburgh Masker have given way to altered auditory feedback (AAF) phone apps, while tools such as electro-palatography now support articulation therapy, and augmentative and alternative communication has become increasingly sophisticated.

On the move

Many people noted the difficulty they had moving materials, therapists and patients around. Early qualified therapists spoke of a range of transport necessities:

- “We used to walk everywhere, because we didn’t have a lot of money… we would walk from Buccleugh Place [in Edinburgh] over to the Royal Infirmary, and not always in ‘sensible’ shoes.”

- “I couldn’t have afforded a car. When it was quite far away, like Kincardine, which was about the furthest point out from Dumfermline, I would go on my bike.”

- “Half past seven in the morning I would catch a bus into Canterbury to catch another bus out of Canterbury to go to Folkestone or… the Margate area.”

- “I travelled the length and breadth of Argyll, and I had to work out things like boat and ferry timetables.”

Many therapists worked across a wide range of clinics and spoke of their cars being their offices, complete with case notes and therapy materials.

One participant reported that a school “hadn’t got a room for me to treat anybody in, so I packed two boys into the car, took them to [the next village] for the morning and treated them there. I did check the car insurance first.”

Another recalled gaining a mobile clinic thanks to a Blue Peter television appeal.

In November’s Bulletin Jois Stansfield dipped into the IJLCD: a history of innovation, science and research in the profession.

Speech and language therapy practice has come a long way in the past 75 years, thanks to the work of clinical innovators, researchers and academics. Much of the change can be traced through articles in the International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders (IJLCD) and its predecessors.

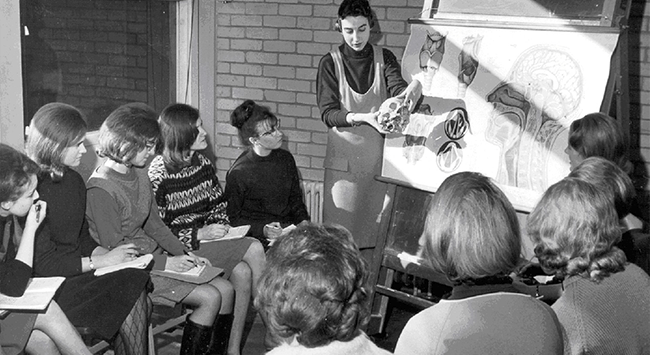

With regard to innovation, I found a very early example in the form of a model speech clinic featured in the 1946 issue of the journal, from two final-year students who won a College of Speech Therapists competition (image 1).

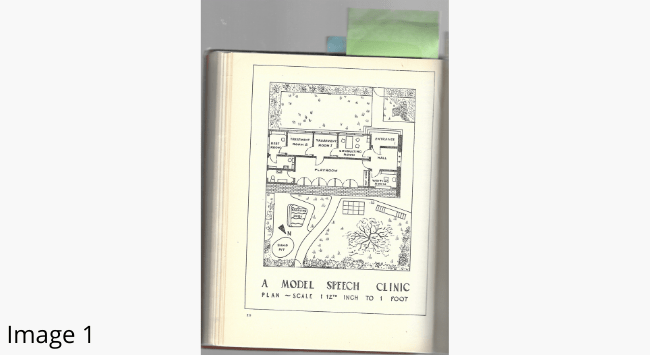

The following year there were instructions on how to construct a test to assess the mental level of children with delayed speech (image 2), no small feat when the usual speech therapy kit comprised little more than a set of hand mirrors, tongue depressors and some straws.

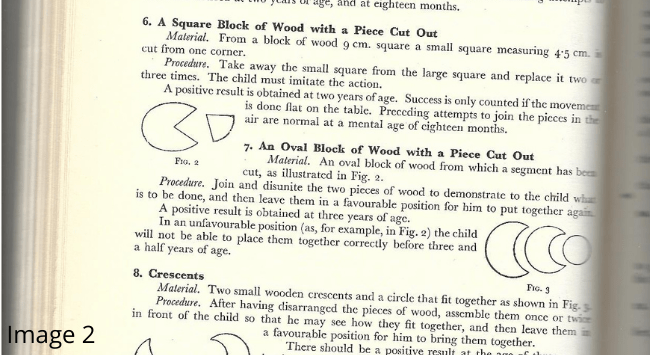

By 1950, a paper described ‘a new aid to speech therapy’, which was a blowing bottle used to displace water (image 3).

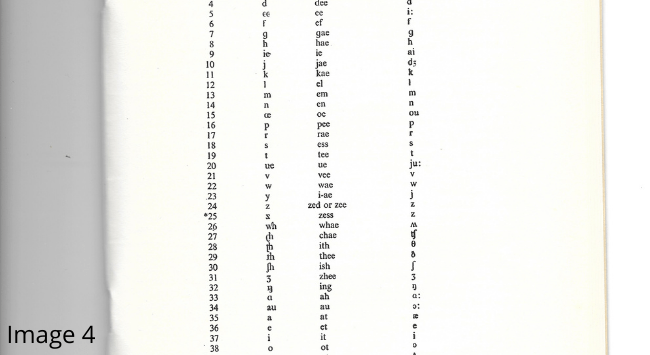

In 1965 an article appeared debating the (short-lived) initial teaching alphabet (ITA) (image 4) as a medium for speech therapy, concluding, unsurprisingly that ‘it depends’ but may be of value.

Over the years SLTs showed themselves to be a resourceful lot. One paper, for example, reported getting permission directly from the Bank of England to take an increased dollar allowance to the USA, when there was a £50 cap on what could be taken out of the UK (1964). While there were fewer personal stories in later years, the various editorials continued to demonstrate this resourcefulness across the profession.

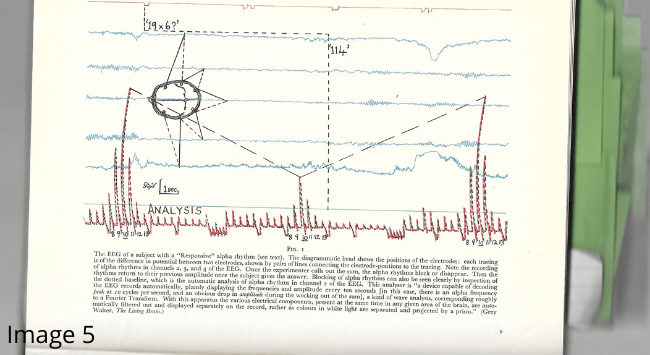

Scientific advances were traced in some papers. 1954 saw the journal’s first colour image, demonstrating the use of the electroencephalogram (EEG) with speech disorders (image 5).

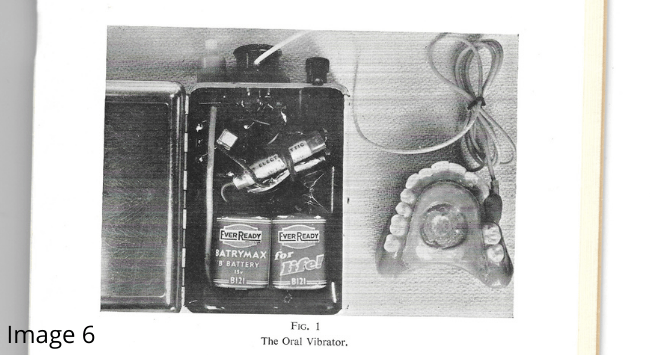

Some other technology appears very strange looking indeed to the modern eye – an item in the 1959 journal resembles a makeshift bomb, but is in fact an early laryngeal vibrator for laryngectomy patients (image 6).

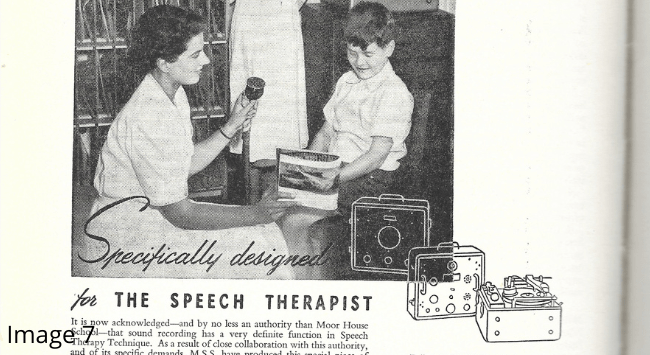

Between 1945 and 65 there were 11 papers on instrumental technology, with a further 35 between 1966 and 2010. In 1950 the first advertisement for speech recording appeared (image 7).

The ability to record is one area where major change has taken place, moving from machines which required almost a whole room to function, through to reel-to-reel recorders, cassette recorders, mini-discs, CDs and present-day miniature digital technology.

Research came to the fore in the journal very gradually, however successive editors have continued to raise the research standing of the journal. Early research papers from medics, psychologists, and audiologists have gradually been superseded by those from SLTs, both from the UK and abroad.

Across the years, developmental speech and language disorders, aphasia and dysfluency appeared most often. Increasing rigour in researching and in reviewing has led to both quantitative and qualitative reports which contribute considerably to the knowledge base of the profession.

Going forward, I hope to see a journal that is inclusive, supporting good quality research across the profession, whether it be basic science, technological developments or clinical practice, so that it continues to reflect the best our profession can achieve.

Jois reflects on some of the figures who inspired her passion for speech and language therapy history.

Denyse Rockey

Denyse Rockey, a life member of the RCSLT, published the only full-length book on the speech therapy of 19th-century Britain (Rockey, 1980). The book focuses on stuttering, at the time seen as closely related to natural speaking and oratory, while being an exemplar of other disabling speech difficulties.

Rockey considers the people who stuttered, the professional responses to the condition, and the many and various approaches attempting to cure or alleviate the condition.

Her comment that stuttering was “open to numerous interpretations and antidotes yet strangely elusive to all” (1980: 253) could still be said to be the case in the 21st century.

It is the first and, to date – despite being 40 years old – the only, comprehensive academic study of British speech therapy in the 19th century.

Margaret Eldridge

Margaret Eldridge, a founder member of both the UK and Australian professional bodies, gives an erudite overview of speech therapy history internationally, considering parallel developments in the UK, eastern and western Europe, Australia and the US (Eldridge, 1968).

She traces the profession moving from trial and error, to increasing professionalism in the 1930s, becoming part of wider established health systems during and after the Second World War. What is striking from Eldridge’s book is the similarity in direction across almost all the countries considered (despite the interruptions of war).

Unfortunately Rockey’s and Eldridge’s books are out of print, but both can be found on the second-hand market.

George Sykes

In 1962, George Sykes produced a dissertation on the history of British speech therapy over the first half of the 20th century (featured in Bulletin in May 1971 and again in August 2015 when he was finally reunited with a copy).

His work included interviews with the heads of every school of speech therapy then in existence and an index of the CST journals (logged, he said, on “an Olivetti Letera 32 typewriter, a double drawer of handwritten index cards, and a shoe box of Hollerith punched cards for the statistics”). The dissertation, part of the RCSLT archive, comes highly recommended as an in-depth view of the profession’s history by an outsider.

So why are these people inspirational? For me, their work opened the door to completely new perspectives on our profession. They demonstrated attention to detail, amazing tenacity in the days before easy access to data via the internet, and a passion that enables those of us interested in professional history today to locate obscure and often forgotten material that enriches our understanding of where we have come from.

Speech and language therapy in the UK owes a lot to our international predecessors.

Europe in particular produced people who formed the knowledge base upon which we built our practice. In the 19th century, these were predominantly men, reflecting the structure of society at the time.

Paul Broca (1824-1880) from France, and Carl Wernicke (1848-1905) from Germany both identified areas of the brain vital for language.

Manuel Garcia (1805-1906), a Spanish baritone and subsequently voice teacher and innovator, worked in France, inventing the laryngoscope in 1854 to observe the vocal cords directly.

Theodor Billroth carried out the first laryngectomy in 1873, with Carl Gussenbauer creating artificial larynxes for his patients.

Adolf Kussamaul published Die Storungen Die Sprache (Disorders of Speech) in 1877.

Hermann Gutzmann (1865-1922) had a speech and language therapy service in Berlin by the beginning of the 1900s and published a number of books on ‘dysphemia’, or stuttering.

The final name of note in this small selection is Emil Froeschells (1884 -1972) from Austro-Hungary. Following his medical qualification in 1907 he worked with children with speech problems and his Viennese clinic became world famous, offering informal education to interested people from around the world until, as a Jew, he and many others found it necessary to escape from Europe in the 1930s.

In the 20th century the USA became increasingly influential, leading the way on children’s speech disorders through the work of Edward Scripture (1864-1945) and Sara Stinchfield (1885-1977), and in stammering therapy through Charles van Riper (1905-95, who also wrote fiction as Cully Gage).

Judy Duchan hosts a website on US (and wider) speech and language therapy history for those interested.

The early British speech therapy registers indicate that a small number of therapists moved abroad, mainly (although not exclusively) to English-speaking countries, contributing to the development of the profession in Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Meanwhile Bulletin and Journal indicated an interest in international developments over the years, with articles on Fiji, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Nicaragua, Russia, Pakistan, Paraguay, St Lucia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Uganda, as well as (other) English-speaking and European countries.

The profession formed national and international bodies to offer professional support.

The International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatics (IALP), whose current President is Professor Pam Enderby, was formed in 1924, with early membership from Austria, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands. Today it represents national associations almost from A to Z: Australia to the USA (although disappointingly not Zambia or Zimbabwe) by way of Brazil, Egypt, the Philippines and Taiwan.

More recently (1988), European colleagues formed the Comité Permanent de Liason des Orthophonists-Logopèdes de l’UE, more easily known by its acronym CPLOL (recently renamed ESLA – the European Speech and Language Therapy Association). Both of these organisations run conferences bringing together a multitude of colleagues, languages and ideas.

Cultural competence is essential in any speech and language therapy service, and there is a growing body of literature from across the world on what works where.

International communication, whether face to face or virtually (more necessary in recent times), can benefit our services by opening our eyes to different approaches and beliefs.

The Bulletin legacy

Charting the history of the RCSLT’s professional magazine.

The College of Speech Therapists (CST) had a difficult gestation and birth, drawing together two competing organisations: the Society of Speech Therapists and the Association of Speech Therapists, which were both established in the 1930s.

The journal Speech, founded in 1935, had taken the role of both academic journal and news bulletin for the Society of Speech Therapists, and as the Association of Speech Therapists had no similar publication, the CST agreed to adopt Speech as the professional journal. Following several name changes, Speech became known as the International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders.

At the time, a need for a less formal publication was recognised, and this resulted in the CST News Bulletin, first published in March 1945.

Formality is a relative concept, and by today’s standards the first editions of the News Bulletin are very formal indeed. Meetings and votes of thanks are reported in earnest and tedious detail. No first names were seen, unless someone had recently married, with married women being known by their husbands’ names (eg Mrs John Smith).

The first edition of Bulletin was characterised by exhortations to members to be collegiate, and to contribute to the CST and Bulletin alike.

Due to the wartime restriction on paper, this first edition was published on four sides of foolscap paper, with dense text, no illustrations and, of course, no colour. Each of the 1945 editions were edited by a different person, but themes rapidly emerged.

Editorials requested contributions and bemoaned poor responses, reports of Area (formal, prestigious) and District meetings (still formal but apparently less important), seem to reflect the divisions of the CST’s predecessors, and there was a how-to-do-therapy article from a senior contributor in each issue.

The editor of the third edition was from Glasgow and this was reflected in the emphasis on Scotland, the ordering of the Area news (Scotland first) and two articles by Dr Anne McAllister, the founder of the Glasgow School of Speech Therapy, written to ensure her contribution to the profession was recognised.

The fourth edition listed membership of all the CST committees, appearing to include a good half of the registered therapists. It was also the first to publish letters to the editor, with one taking exception to the contents of an earlier therapy article, while another thanked members for their entry to a competition to design a model speech therapy clinic. A ‘personal’ column was also suggested and established from 1946 – something that has continued in the magazine in the decades following.

Over the decades Bulletin has had many facelifts, and today the range of material would be unrecognisable to the founders of the CST. Nevertheless, Bulletin then, as now, reflected members’ interests. Tracing the changes made to the magazine helps us to see how the profession has viewed itself during the past 75 years.

Download a timeline of speech and language therapy ‘firsts’ (PDF)

Covers through time

|

|

|

| January 2001

Jumping forward to 2001, the once text dense pages of Bulletin have moved to a slightly more modern layout that we might recognise today. This issue features a letter from the editor, news of the New Standards ten million pound grant for English education authorities towards speech and language therapy, as well as features on hearing impairments and treating vocal nodules. Read the January 2021 issue (PDF). |

June 1945

Only the second issue of Bulletin (then known as The Bulletin) ever printed, the June issue of 1945 reported on a ‘successful annual conference and dinner’, member news, and even outlines structure of Bulletin as we know it today. The then editor, Mary Topping, requested members to submit their letters to the editor, book reviews and many other features you will find in today’s Bulletin. Read the 1945 issue (PDF). |

October 2005

In 2005 the RCSLT celebrated it’s 60 year anniversary, the issue walks members through the ages, from World War II to 2005, passing through the swinging ‘60s and the Millennium. In 2005, the profession welcomed 200 members to its conference in Birmingham, announced the launch of an online CPD diary, and looked forward to another year. Read the October 2005 issue (PDF). |

Shining a light on some of the strong women who helped to build the speech and language therapy profession as we know it today.

Many of the pioneers of the speech and language therapy profession, including all 18 of the RCSLT founder fellows, were women. International Women’s Day, recognised on 8 March, provides a great opportunity to celebrate our place as a strong, female-led profession, and the women who helped to make it that way.

Elsie Fogerty

Elsie Fogerty (1865-1945) established what is now the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama at the Albert Hall in London in 1906. She came from a privileged background, but had to find a way to earn a living when her father became ill and unable to support the family.

By 1912 she was teaching about elocution, voice production and ‘speech defects’, and began working as a speech therapist in St Thomas’s Hospital. She was involved with the school until her retirement in 1942.

Winifred Kingdon Ward

The Great War decimated the male population in the UK, and between the wars around a fifth of women of ‘marriageable age’ remained single throughout their lives. Many of these women turned their energy to forging careers for themselves, including many early speech therapists.

Winifred Kingdon Ward (1884-1979) was one such SLT. She studied singing and speech and worked with injured servicemen during the Great War, subsequently establishing not one, but two schools of speech therapy. The first, in 1929, was at the West End Hospital (now University College London).

She left in 1935, ostensibly to travel, but also following a disagreement with one of the senior staff, of whom she disapproved because of his ‘irregular’ (ie adulterous) relationship with a woman described as either his laboratory assistant or an SLT.

The London Hospitals School (now at City, University of London), her second establishment, was founded in 1942. Winifred demonstrated huge tenacity by achieving all of this in the middle of wartime London, and went on to author a number of important publications.

Anne McAllister

Anne McAllister (1892-1983) was a Scot whose work as a phonetician in Glasgow morphed into speech therapy.

‘Dr Anne’, as she became known, first started teaching about speech disorders in 1919, and established the Glasgow School of Speech Therapy (celebrating 85 years this year) in 1935.

As with so many other women in the field, Anne was renowned for being highly intelligent and knowledgeable, but she did not hold back when she was displeased.

Joan van Thal

Joan van Thal (1900-1970) was of Dutch and English heritage, and educated in England. She had wanted to become a doctor, but was not accepted to study medicine owing to her poor eyesight. Under the guidance of Elsie Fogerty after the Great War, Joan became an expert on cleft palate, publishing a book on the topic in 1934.

Her greater claim to fame, however, is that during World War II she appears to have been the catalyst in bringing together the two competing speech therapy associations formed in the 1930s, resulting in the establishment of the College of Speech Therapists (now the RCSLT).

There are so many other impressive women who built this amazing profession – the stars in my own ‘speech therapy sky’ include Betty Byers Brown, Caroline Dunsmore (my wheelchair-using, polio-surviving boss in Canada), Brenda Kellett and Pam Enderby.

From patients to service users

When the College of Speech Therapists was established in 1945, service users were known as ‘patients’. For many that was an accurate description, as they needed to wait patiently for the limited speech therapy service that was available, and many areas of the country had no service at all.

The register of 1945-6 listed 46 SLTs practising in London, 12 in Lancashire (which included all of Manchester, Liverpool and the rest of the county) and one in Norfolk.

Scotland was relatively well served with 39 therapists, but Wales listed only one, and Northern Ireland none. This was pre-NHS of course, but even when free speech therapy became available in principle, the service grew very slowly during the 1950s and 60s.

The Quirk Report of 1972 made sweeping changes to the level of service provision, recommending six therapists per 100,000 in the population – a quadrupling of full-time equivalent SLTs at the time.

Later, Enderby and Phillip increased this recommendation further to 23 therapists for the same population, and today there are almost 19,000 therapists for a population of nearly 68 million. You can work out the ratio!

Over the years, our ability to recognise the needs of service users has also changed. Many older SLTs speak of being trained mainly to work with ‘articulation’ difficulties, and it was not until the late 1960s that linguistics raised its head in the speech therapy world, with pragmatics coming later still.

On my own course, we had only one hour a week of linguistics for three terms. My ‘finals’ case book from 1972 described 13 ‘patients’ in detail (present-day students take note, 13!).

There is little evidence anywhere in the case book that this linguistic theory was put into practice, although language tests were reported (the Watts vocabulary test, the recently published Reynell scales and, for adults, the Minnesota Test), as was working with people to increase language, and articulation, voice and fluency skills.

What that case book also shows is how the age range of patients (they were still patients in 1972) has changed. Most of the children were at school and the oldest adult was only 63. Today I would expect ‘birth to 100-plus’ to be a more accurate reflection of our service users’ ages.

I smiled when I realised that I had included a thank you note from the parents of one child, whose family included 11 children, five of whom had some ‘speech’ difficulty. I am astonished and impressed in retrospect that this child was brought to clinic every week without fail and the parents followed advice on what to practise as homework.