This page gives guidance and best practice on the role of speech and language therapy in supporting people living with Parkinson’s.

Information for the public is also available. For other sources, see our Resources page

Last updated: December 2025

Development of the guidance

This guidance is a joint endeavour between Parkinson’s UK and RCSLT.

RCSLT are grateful for the support of Parkinson’s UK in developing this much needed guidance. The guidance was developed by a working group of speech and language therapists with representation from Parkinson’s UK. There was representation from England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as well as across specialities and age ranges. The group had representation from research active SLTs. RCSLT are extremely grateful for the input of the experts by experience who coproduced this guidance. Their insight has been invaluable.

Consultation

A draft of this document was open for consultation to the public and members of RCSLT. RCSLT are grateful to all respondents for their input during the consultation. Responses were received from speech and language therapists, PwP and their family/carers, researchers, Parkinson’s specialist nurses, Parkinson’s UK, MSA Trust and PSP Association. All comments were reviewed and changes made to the draft where appropriate.

Development

Communication for people with Parkinson’s (PwP) can be affected at any stage of the condition with consequent significant impact on family, work and social roles. This can be due to changes in motor aspects of speech (such as voice volume, articulatory clarity or overall intonation) as well as to subtle changes in posture and facial expression.

Similarly, difficulties with eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) is a frequent and clinically relevant symptom of early to advanced stages of Parkinson’s. EDS difficulties can lead to aspiration pneumonia and therefore its management should be prioritised.

Timely and accurate advice and guidance at every stage of a progressive condition can aid not just the PwP but also their family/social and work circles.

The drivers for this guidance are:

- Recent evidence for effective speech and swallowing interventions and the overall value of exercise in reducing the severity of symptoms has dramatically increased over the last 10 years (Perry et al, 2024; Sackley et al, 2024; Li et al, 2023; Flynn et al, 2022; Tsukita et al, 2022;Ahlskog, 2018).

- The use of technology for assessment (use of speech as a biomarker to aid diagnosis), for treatment (cueing and biofeedback) and for access to therapy has increased (Rusz et al, 2024).

- The only available relevant clinical guidelines for the areas of swallowing and communication for PwP are the Dutch Guidelines for Speech-Language Therapy in Parkinson’s by Kalf et al (2011) (English translation). (These were updated in 2018, but only in Dutch).

- The German Society of Neurology has issued a guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia and specifically the management of PwP (Dziewas et al, 2021).

- The progress since the last Cochrane Review is significant for communication and eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) (Herd et al, 2012).

A systematic review may rightly focus on evidence for therapy based on randomised controlled trials, whereas the scope of this clinical guidance is much wider, considering the following:

- assessment and treatment strategies

- the ICF model of disability and health

- the PwP and their caregiver’s perspective

- linking the available therapies with the individual needs of the PwP and their journey.

In summary, this guidance aims to provide decision support for:

- clinicians who need to know what, when and how to assess, advise and treat PwP

- PwP who need to know when to ask for speech and language therapy and what to expect as well as what they can do for themselves

- neurologists/GPs who need to know when to refer to an SLT.

Intended outcome for SLTs

The intended outcome is to increase knowledge and confidence on the available evidence for the assessment and management of eating, drinking, swallowing, communication and saliva problems for PwP in order to:

- strive for equality of access to therapies with good evidence

- understand the risks of deviating from the guidance for the care of PwP

- support service development for specialist clinical care provision

- acknowledge ‘red flags’ including when to refer on

- encourage the development of multidisciplinary working

- identify areas of further development both clinically and in research.

Intended outcomes for PwP

The intended outcomes for PwP are to:

- understand the way Parkinson’s can affect communication in general including speech, EDS and saliva control

- provide PwP and their caregivers with information on what the available treatments are for communication, swallowing and saliva management

- provide PwP and caregivers with the necessary information to request access to therapies

- encourage ways to self-manage, including ways to motivate themselves to maintain the gains from therapy.

Intended outcomes for clinicians, health commissioners and other healthcare professionals

The intended outcomes for clinicians, health commissioners and other healthcare professionals are to:

- inform referrers about the best treatments for PwP

- inform about the risks of not adhering to national and international guidance

- encourage specialist service multidisciplinary team working

- support the links between inpatient, outpatient and community care

- inform clinicians about red flags/signs to monitor and be aware of.

Implementation

While studies continue to examine the optimal dosing of, targets for and delivery models of speech and swallowing intervention for PwP (Sackley et al, 2024), there are studies that show swallowing and communication issues of PwP are under-addressed by rehabilitation referrals (Roberts et al, 2021).

PwP who self-identify as having difficulties with activities of daily living, work-related or leisure activities, eating and drooling are less likely to receive rehabilitation than those reporting mobility issues (Nijrake et al, 2008). Despite evidence supporting multidisciplinary and proactive rehabilitation in Parkinson’s, most referrals are made to a single service as a reaction to falls or severe dysphagia. Opportunities for optimising care through proactive rehabilitation interventions are missed (Roberts et al, 2021).

This guidance aims to outline the best available evidence for the management of communication and swallowing and saliva problems in PwP throughout the stages of the condition and with consideration of the support needs of family and caregivers.

Selecting speech and language therapy measurement tools and sources of evidence

The group developed this guidance according to international standards for guideline development, mainly the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). The group decided on the key questions and the outcomes that matter the most for the population group of the guidance.

Four separate searches utilising PubMed, Embase and PsycInfo databases (through the Ovid interface) according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were performed in August 2024. The search syntax encompassed a range of keywords related to speech, voice, swallowing and saliva, Parkinson’s, atypical parkinsonism, PSP, MSA and CBS. Restrictions were applied for publication dates (1990-2024), peer-reviewed journal articles and relevant book chapters, written in English. The following inclusion criteria were established for the review:

- Studies should involve cohorts of more than three people diagnosed with Parkinson’s or atypical Parkinson’s.

- Participants should be adults only.

- Studies must investigate the impact of pharmacological, surgical or behavioural treatments on communication, swallowing and saliva control through clinical rating scales, perceptual or acoustic analyses or specialised questionnaires.

- No reviews or meta-analyses can be included as primary evidence.

The group then rated the data according to the evidence that best applied to each outcome (considering the risk of bias) as strong or weak and in favour of or against an intervention. Strong recommendations suggested that all or almost all members would choose that intervention. Recommendations were more likely to be weak when the certainty of the evidence was low, when there was a close balance between desirable and undesirable consequences, when there was substantial variation or uncertainty in patient values and preferences and when interventions required considerable resources.

Quality assessments of the included studies were performed with the adjusted Parkinson’s-specific assessment form designed by Den Brok et al (2015), which was based on the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale (Wells et al). The scores ranged from 0 to 22 and higher scores indicated better study quality.

Limitations of the guidance

This guidance has some limitations that need to be considered:

- The assessment and treatment of people with atypical Parkinson’s is limited to case studies and observations. We have included as much as possible, but it is not an exhaustive account, or indeed strong evidence. It should be used as evidence for the need for further studies.

- This guidance is not intended for university curriculum guidance. Its primary aim is clinical guidance and not academic.

Communication and swallowing can be affected by pharmacological and surgical management considerations. This guidance can refer to some of the recent literature on the effects of these treatments on communication and EDS, but it cannot provide a comprehensive account of all the factors involved.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations have been used within the guidance

ANS Acquired neurogenic stuttering

CBS Corticobasal syndrome

EDS Eating, drinking and swallowing

FEES Fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation swallowing

ICF International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health

LSVT Lee Silverman voice treatment

MDS-UPDRS Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

MSA Multiple system atrophy

PEG Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

PSP Progressive supranuclear palsy

PwP Person with Parkinson’s

RCSLT Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

RCT Randomised controlled trial

REM Rapid eye movement

SIT Sentence intelligibility test

SPL Sound pressure level

STN Subthalamic nucleus

VAS Visual analogue scale

VFS Videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing

VHI Voice handicap index

Key recommendations

- Based on the evidence reviewed, LSVT LOUD is highly recommended for treatment of communication problems in PwP.

- Based on the evidence reviewed, the use of singing groups is recommended for treatment of communication problems in PwP.

- Based on the limited evidence, the use of biofeedback devices is recommended at an experimental level mainly as a ‘cue’ to increase vocal loudness.

- Based on the limited evidence, the use of SpeechVive/delayed auditory feedback/masking noise is recommended at an experimental level to increase vocal loudness.

- Based on this limited evidence the use of groups for therapy is recommended at an experimental level to increase social participation and vocal loudness.

- Electrical stimulation therapy is not recommended for swallowing therapy in PwP.

- Providing feedback on individual swallowing function from VFS examination is highly recommended.

- Expiratory muscle strength training and sensorimotor training for airway protection are highly recommended treatments for cough strength training in PwP.

- Use of cueing strategies (auditory cues or chewing gum) to increase spontaneous swallowing of saliva is recommended for the management of sialorrhea in PwP.

- PwP in the late stages should always be managed by a team of experts.

- SLTs should use a validated and appropriate method to measure change of any intervention and should not rely solely on subjective self-reporting.

- SLTs should enquire after and consider the variable effects of pharmacological and surgical treatments on communication and swallowing problems of PwP, especially in the late stages of Parkinson’s.

- When a PwP is admitted for surgery, whether elective or emergency, it is paramount to consider medication swallowing. An assessment of swallowing before and immediately after the procedure by a trained health professional is warranted. Given the link between adequate medication intake and swallowing ability it is vital to maintain medication intake so that the person can continue to swallow safely.

- Connecting the layers of healthcare through a network across disciplines and healthcare settings could deliver a proactive model of care and reduce hospital admissions.

- SLTs should actively encourage communication between healthcare settings and between caregivers and PwP.

- Despite the limited data, hypomimia and its impact on communication and social interaction should be considered and discussed with the PwP if it is raised and deemed clinically appropriate.

- Telehealth is recommended in specific well-defined treatments such as LSVT LOUD and EMST, but the clinician should always be aware of measuring outcomes in a valid and reliable way.

About Parkinson’s and atypical Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disorder, characterised primarily by loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra. People with Parkinson’s (PwP) may experience tremor, mainly at rest, bradykinesia (slow movements), limb rigidity, gait, balance and speech problems. Symptoms generally develop on one side of the body, slowly over years, but the progression may differ. Prevalence is approximately 200 cases per 100,000 population and the incidence is about 25 per 100,000 population.

The cause of Parkinson’s is probably multifactorial. Diagnosis remains clinical and is based on motor manifestations, aided by imaging investigations (DaT scan, MRI) and genetic testing. Levodopa is the main pharmacological treatment for Parkinson’s. Medical management has improved parkinsonian symptoms and quality of life through pharmacological or neurosurgical interventions. However, challenges remain in treating communication, swallowing, saliva and other non-motor and motor symptoms. These challenges, in turn, affect the ability of PwP to maintain social and family roles and employment.

Identifying the extent to which these symptoms are present as early in the diagnosis as possible and treating these symptoms earlier could support independent living.

Atypical parkinsonism

Atypical parkinsonism, also called Parkinson-plus syndrome, is when the person has parkinsonism plus other features including early balance problems/falling, poor reaction to the drug levodopa, early cognitive problems and impaired control of blood pressure/bowel/bladder. Due to the frequent early occurrence of speech and swallowing difficulties in atypical Parkinson’s the role of the SLT is crucial.

More specific information on the characteristics, the assessment and the treatment of people with PSP, MSA and CBS, follow in this guidance.

Table 1 offers a summary of the specific speech and swallowing symptoms for people with atypical Parkinsonism that may be apparent earlier (less than two years after diagnosis) and necessitate further investigations.

Table 1: Summary of the main speech and eating, drinking and swallowing characteristics of atypical Parkinson’s based on the limited number of studies available. For further information please refer to the specific section of this guidance.

| Atypical Parkinson’s | Speech characteristics | Eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) characteristics |

| PSP | Early dysarthria with mixed presentation (hypokinetic, spastic)

Palilalia; stammer-like speech. |

More awareness of EDS difficulties

Delayed swallow reflex. |

| MSA | Early symptoms with mixed presentation

Inhalatory stridor Arytenoid tremor. |

Delayed bolus transfer

Oesophageal dysmotility Tongue incoordination. |

| CBS | Apraxia of speech

Yes–no reversals. |

Fragmented swallow, piecemeal, with tongue incoordination. |

Healthcare management principles

Healthcare management in PwP follows the principles of managing complex conditions as set out through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF Model, 2001). This way of structuring the needs of PwP is best served in an integrated multidisciplinary approach that allows the PwP to be at the centre of the healthcare and values the role of the caregiver.

The ICF model for Parkinson’s

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) classification system can be used to describe treatments and outcomes at three levels:

- physiological and psychological functions (body functions) and anatomical parts (body structures)

- execution of a task or action (activities)

- involvement in a lifetime situation (participation).

The complexities of Parkinson’s stem from:

- motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, reduced amplitude of movement, tremor at rest, rigidity, pain, gait and balance issues, speech and swallowing difficulties

- non-motor symptoms caused by Parkinson’s itself, such as olfactory dysfunction, constipation, depression, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder, dysautonomia and some executive dysfunction problems

- side effects of pharmacological or surgical treatments

- variability in the personal, social and community circumstances of PwP.

Multidisciplinary collaboration – integrated care

Specialised care generally refers to high-quality care that is designed and tailored for a specific condition or patient population. It is delivered by professionals with a specific interest and competence in that area (Sturkenboom et al, 2024). Figure 1 in Sturkenboom et al (2024), ‘Overview of interdisciplinary overlap between specialized Allied Health Professionals for Parkinson’s disease’, provides a useful illustration of interdisciplinary involvement.

Specialised healthcare is essential for PwP as there may be considerable variation in terms of their motor and non-motor symptoms, the way they present and how they impact daily life.

According to Bloem et al (2020) there are three pivots of care for PwP: care should be delivered closer to home with remote monitoring; PwP and their carers should be empowered to self-manage the condition; care should be proactive and timely with precision medicine/personalised medicine.

Integrated care, based on a coordinated multidisciplinary team approach, is becoming the gold standard of care for PwP (Fabbri et al, 2024). Ghilardi et al (2024) have shown that PwP who have specialised enhanced rehabilitation in a specialist centre have better outcomes than those managed by expert neurologists with community programmes for exercise and other allied health interventions. The greatest effects were seen in people in the early stages of Parkinson’s who committed to a high amount of vigorous exercise per week.

One possible reason for the significant difference between outpatient therapy and therapy delivered from a specialised centre is the opportunity in a specialised centre to communicate directly with the neurologist and other allied health professionals to change the course of therapy (Ghilardi et al, 2024).

In summary, long-term benefits to motor function and quality of life in PwP can only be achieved through a systematic programme of specialised enhanced rehabilitation interventions.

Person-centred approach

Person-centredness is increasingly recognised as a crucial element for quality of care. It has been defined as “providing care that is respectful towards and responsive to individual patient preferences” (Institute of Medicine (US), 2001).

Person-centredness and self-management support are part of the chronic care model (Wagner, 2010). This model focuses on the collaboration between well-informed, active service users and prepared, proactive health professionals. (See RCSLT’s guidance on personalised care.) By providing decision support towards a structured, evidence-based, continuum of care this guidance aims to further support use of this model.

A person-centred approach is particularly appropriate for communication and eating, drinking and swallowing guidance because the interventions need to fit with the needs, motivations and abilities of the PwP and their caregivers (Nisenzon et al, 2011). Increased self-control increases motivation (Chiviacowsky et al, 2012). Given the complexity of symptoms, it is paramount that the PwP is empowered to make their own informed choice about their priorities and the interventions they receive.

Motivation for change

Respect for the PwP’s autonomy and a focus on independence are essential when aiming to provide optimal speech and language therapy.

Self-management is defined as an individual’s ability to cope with symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes associated with a chronic condition (Van der Eijk et al, 2013; Barlow et al, 2002). By supporting the PwP and the caregiver to self-reflect, prioritise and apply problem-solving skills related to issues of activity performance and participation, self-management can be achieved (Keus et al, 2014). Technology can play a role in supporting self-management. See section on technology for treatment for more information.

Maintenance of speech after intensive rehabilitation

Maintenance of speech outcomes following speech therapy has been poorly investigated, but some strategies have been found to help (Finnimore et al, 2022). These include partnerships, self-reflection, maintenance barriers and facilitators, goal setting and revision of LSVT LOUD skills, such as in LOUD Crowd or Loud for Life or by joining a coir (such as Sing for Joy choir) (LSVT LOUD is an intensive, evidence-based voice therapy programme designed to improve vocal loudness and clarity in people with Parkinson’s – for further information see section on Communication interventions.

Stage-specific needs

The timing and right dosage of intervention has not yet been investigated for every stage of the journey of PwP. Some studies indicated that early and intensive exercise can be more effective than mild or moderate intervention in slowing the progress of the symptoms’ severity and maintaining employment (Tsukita et al, 2022). However, there are limited studies looking into the right timing of intervention and long-term outcomes of early versus late therapy.

A recent case-based publication by Weise et al (2024) provided an illustration of the different needs and ways of working in a team at different stages from diagnosis to palliative care. More similar studies with long-term outcomes would be useful.

Support and training for caregivers

Reduced effectiveness of communication can cause frustration and dissatisfaction in both PwP and their communication partners (Vatter et al, 2019; Mosley et al, 2017). Communication challenges can directly impact relationships and mental wellbeing, potentially contributing to carer burden and third party disability.

Spouses of PwP who have cognitive impairments and dementia describe higher levels of relationship dissatisfaction and care burden and a reduced number of positive interactions with their partners (Vatter et al, 2019). Family members describe the need for support to address the broader impact of communication difficulties and their own unique needs resulting from communication difficulties. Therefore, intervention in this area must carefully consider the individual needs and goals of family members or carers related to communication difficulties arising from Parkinson’s.

Speech and language therapy for PwP: core areas for intervention

There are three core areas that speech and language therapy addresses in PwP: communication; eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS); and saliva control. Below, we will present the main characteristics and prevalence for each area.

Communication

Speech in Parkinson’s is affected by common pathological manifestations such as akinesia, bradykinesia and hypokinesia, leading to the reduced amplitude and automaticity of speech movements (Bloem et al, 2021; Duffy, 2019; Ho et al, 1999). Characterised as hypokinetic dysarthria, these speech difficulties represent an early and frequent sign of Parkinson’s (Rusz et al, 2022).

The main perceptual characteristics of hypokinetic dysarthria are monopitch, monoloudness, reduced stress, short phrases, variable rate, short rushes of speech and imprecise consonants (Rusz et al, 2021; Darley et al, 1969). Since speech problems can worsen as Parkinson’s progresses (Skodda et al, 2013) dysarthria gradually becomes one of the most disabling symptoms affecting social interaction and the quality of life of PwP (Finnimore et al, 2022).

Although pharmacological and surgical treatments of motor symptoms might relieve some aspects of dysarthria, mainly in the early stages (Rusz et al, 2021), they can have a negative impact on overall speech intelligibility (Tripoliti et al, 2014). By contrast, behavioural treatments such as LSVT LOUD (Ramig et al, 2018) are shown to have a positive outcome on communication. Therefore, SLTs could and should play a pivotal role in the management of communication needs of PwP throughout the condition process.

Acquired neurogenic stuttering or palilalia

PwP can experience palilalia, also known as acquired neurogenic stuttering (ANS). ANS is the preferred term to describe this debilitating speech disorder to differentiate it from developmental stammering. ANS is characterised by accumulative rapidity and declining loudness as well as repetition of speech (Benke et al, 2000).

ANS can present as ‘festination and/or freezing of speech’. In particular, festination of speech is described as “rapid, incomplete in range and amplitude movement of the articulators resulting in compulsive-like repetition of all or part of a word” (Benke et al, 2000, p. 323). Freezing of speech is the “complete, albeit temporary, breakdown in movement, both of breathing and speech” (Benke et al, 2000, p. 323).

Both festination and freezing of speech are triggered by speech (task specific) and tend to improve by singing or whispering. They can be likened to the freezing and festination of gait, with increasingly faster and smaller in amplitude movements (Mekyska et al, 2018).

The suggested minimum criterion for the diagnosis of a dysfluency disorder is 3% of the syllables stuttered in a reading passage (Conture, 2001). Most studies use spontaneous speech and a reading passage and count the number of repetitions, prolongations and blocks (eg Tykalová et al, 2015). ANS can be a red flag for PSP diagnosis if it is present early in the condition process (Tykalová et al, 2017).

Understanding the mechanisms of speech disorders and the factors that contribute to them is essential for effective assessment and intervention.

Prevalence of speech difficulties

Prevalence of speech difficulties varies in the literature depending on the way they are measured: some studies use the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), a generic motor scale (Goetz et al, 2019). Part three in the scale has a single item for speech, to be rated from zero (no speech problem) to four (no functional speech) (Goetz et al, 2019).

Data from a large cohort study of 419 PwP using the MDS-UPDRS-III (Perez-Lloret et al, 2011) showed that the presence of dysarthria across the differing stages of Parkinson’s was at 51%, the presence of sialorrhea (saliva problems) was at 65% and the presence of dysphagia (eating, drinking and swallowing problems) was at 46%. It also showed the link to quality of life for each.

When speech is measured by speech-specific recordings and analysis the prevalence rises to 90% irrespective of the condition stage (Rusz et al, 2021).

The prevalence of ANS ranges from 20% (Gooch et al, 2023) to 54.3% (Benke et al, 2000; Tsuboi et al, 2019; Whitfield et al, 2018) depending on the specificity of speech assessment (questionnaire vs specific speech) and the stage of Parkinson’s (prevalence increased as the stage of the condition advanced).

Eating, drinking and swallowing

Eating, drinking and swallowing (EDS) difficulties, also known as dysphagia, occur frequently at any stage of Parkinson’s (Pflug et al, 2019). Warnecke et al (2018) recommended that in the case of Parkinson’s dysphagia it is necessary to examine whether an improvement in swallowing function can be achieved by increasing or optimising the dopaminergic medication on a case-by-case basis.

Prevalence of eating, drinking and swallowing problems

Prevalence of dysphagia varies depending on the ways it is assessed. When using VFSS abnormalities have been found in 75-97% of PwP (Warnecke et al, 2018). Prevalence does not depend on disease duration. Pflug et al (2019) used FEES on 119 consecutive PwP and found that 20% of PwP with condition duration of less than two years showed aspiration.

In a large meta-analysis on the prevalence of aspiration pneumonia and hospital mortality Yu Chua et al (2024) showed that the risk of aspiration pneumonia was three times higher in PwP than in people without Parkinson’s, with an average of 10% hospital mortality. They concluded that early detection of aspiration and multidisciplinary team management can prevent hospital admissions and reduce mortality.

EDS difficulties need to be managed as early as possible to avoid complications such as chest infections (aspiration pneumonia), malnutrition, dehydration, impact on medication management and quality of life.

Saliva control

Sialorrhea is defined as the inability to control oral secretions, resulting in excessive saliva accumulation in the oropharynx (Cardoso, 2018). Drooling is defined as the involuntary spillage of saliva from the mouth from excessive saliva accumulation in the pharynx (Merello, 2008).

In PwP the cause of drooling is not due to excessive production of saliva (Merello, 2008) but rather a reduction in swallowing frequency. Flexed posture or limited mobility adds further difficulties in clearing saliva.

One of the most significant factors contributing to sialorrhea is hypotussia (cough dysfunction) (Dallal-York and Troche, 2024), which reduces the ability of PwP to clear secretions from the back of the throat. The sensory feedback from saliva itself is not remarkable enough in taste or temperature for the cough to be triggered.

Prevalence of sialorrhea

The prevalence of sialorrhea is reported to range from 31% to 86% (Barone et al, 2009; Chou et al, 2007). The discrepancy depends on the method used to assess the accumulation of saliva as well as the characteristics of the population in the studies; it is expected that the prevalence is greater in PwP with dysphagia (Chou et al, 2007). Sialorrhea can be seen in very early stages when PwP list it as one of the most disabling non-motor findings (Khoo et al, 2013; Seppi et al, 2011) due to the social embarrassment and consequent isolation (Miller et al, 2019).

History taking and examination

History taking

The objective of history taking is to gain insight into the severity and nature of the concerns of the PwP and to decide which impairments and activity limitations to target during examination. The individual’s own strategies to overcome difficulties are also recorded.

The therapist aims to assess whether the PwP’s expectations are realistic. It is often the case that PwP are not aware of some specific symptoms and it might be important to involve a caregiver. (For an example of questionnaires for communication see Kalf et al, 2007a; for questionnaires on swallowing see Kalf et al, 2007b; for questionnaires on saliva see Kalf et al, 2007c.)

Speech examination: what and how to examine

There are two main ways to examine speech for PwP, depending on the aim of the assessment: with perceptual tools or with acoustic tools. Ideally, both should be used.

The most widely used perceptual tools are as follows.

- Movement Disorder Society – Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) (Goetz et al, 2019) – This scale contains one question for the PwP and one for the clinician to rate their speech on a five-point scale from zero (no speech problems) to four (anarthric).

- Voice Handicap Index (Jacobson et al, 1997) This is a self-reporting questionnaire containing 10 questions. It gives insight into the impact of voice difficulties but is not diagnostic (Jacobson et al, 1997) and as it relies on self-perception, it does not have high reliability and validity in PwP.

- Sentence intelligibility test (SIT) (Yorkston and Beukelman, 1984). This test is often used to assess how well speech is understood by listeners by means of a percentage of words understood by a listener. It relies on subjective judgement, so a higher number of listeners may be required to improve reliability.

- Frenchay dysarthria assessment This is a complex evaluation of the subsystems of speech that can only be carried out by an SLT (Enderby, 1980).

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS) The VAS is easy to administer and can be used to evaluate various aspects of dysarthria, including its impact on activities and participation (Abur et al, 2019).

- Radboud Oral Motor Inventory for Parkinson’s Disease – Speech (ROMP–speech) (Kalf et al, 2007a) This is a patient-reported outcome measure that assesses the impact of speech difficulties in PwP across several domains, including speech clarity, effort and communication effectiveness.

- Mayo Clinic dysarthria assessment The Mayo Clinic dysarthria rating scale was first used by Darley et al (1975) and more recently by Tripoliti et al (2014) and Plowman-Prine et al (2009). It is the most-used scale to perceptually rank different aspects of motor speech disorder such as respiration, prosody, voice, articulation, rate and nasality.

The choice of perceptual test will depend on the time available, the priorities and communication needs of the PwP and the hypotheses formed by the clinician on the nature and course of the treatment.

Audio and video recording

Acoustic analyses can provide objective markers on different components of speech impairment corresponding with these perceptual characteristics (Rusz et al, 2021). There is no consensus about the ideal acoustic outcome measures used for the evaluation of speech disorders.

However, recording of three simple types of vocal tasks, including connected speech (such as reading, monologue and retelling), sustained vowel and fast syllable repetition, can give us representative speech material to obtain a complete profile of motor speech disorder in PwP (Rusz et al, 2024; Rusz et al, 2021; Patel et al, 2018).

The most used tasks for the acoustic evaluation of speech in PwP are:

- sustained vowel – shows the presence of inappropriate voice function

- alternating and sequential motion rates – measures the motor abilities of the speech articulators and reveals their movement limitations

- monologue and reading passage – reflects a combination of speech-motor execution and cognitive-linguistic processing.

The complete recording protocol for the acoustic evaluation, including the recommended positioning of the recording device, can be found in the guidelines paper (Rusz et al, 2021).

Remote speech assessment

Speech recording and subsequent analysis (through perceptual or acoustic means) can also be performed through a smartphone device, not just with state-of-the-art speech recording equipment.

The smartphone-based approach can offer frequent, objective, real-world assessments with enormous amounts of data in a short timeframe, leading to better sensitivity and stability of speech assessment compared to a single, time-limited laboratory evaluation. Thus, monitoring via smartphone could be extremely valuable in assessing treatment and condition-modifying effects in clinical trials (Lipsmeier et al, 2018).

Pilot cross-sectional studies showed that smartphone-based voice assessment in combination with machine learning techniques might facilitate screening for prodromal neurodegeneration, monitoring daily fluctuations of response to medication and quantifying Parkinson’s severity (Kothare et al, 2022; Omberg et al, 2022; Arora et al, 2018; Zhan et al, 2018). Monitoring PwP through smartphone applications may also capture the way they speak outside of the artificial laboratory or clinic setting, where other factors such as environmental noise, dual-tasking, social interactions, or emotional influence have important roles and thus provide a natural biomarker of Parkinson’s progression (Illner et al, 2024).

The benefits of access and generalisability are counterbalanced by the many challenges in the privacy issues and validation of real-world data. These are obtained without an investigator guiding a recording protocol or labelling specific speech paradigms. The quality of smartphone microphones is typically much lower than that of a professional condenser microphone used in research practice and differs from device to device (Rusz et al, 2018).

Variation in the direction of the microphone and distance from the lips (due to the way the phone is held in each case) combined with background noise mean it is challenging to assess speech in everyday environments.

These issues warrant further investment in technical and clinical innovation before smartphones can be routinely deployed in monitoring communication.

Swallow examination

When assessing swallowing it is important to bear in mind how slower mealtimes or difficulty with eating independently (eg holding a cup or cutlery) can affect the enjoyment and effectiveness of mealtimes and so affect quality of life.

Only a minority of people with Parkinson’s dysphagia are aware of, or report, swallowing difficulties when they are present. Swallowing difficulties may be present before Parkinson’s is diagnosed but go unnoticed (Warnecke et al, 2018).

Therefore, it is important to detect swallowing problems early to prevent issues with swallowing medication, dehydration, silent aspiration, chest infections and malnutrition.

Instrumental methods (such as FEES and VFSS) are the most valid and reliable methods of detecting risk of aspiration and penetration in PwP (Dziewas et al, 2021; Pflug et al, 2019; Simons et al, 2014).

According to Dziewas et al (2021), once Parkinson’s-specific risk factors and Parkinson’s-specific questionnaires are positive, then FEES should be performed. The risk factors found to be the strongest predictors of swallowing difficulties in PwP are:

- delayed mastication (chewing)

- reduced lingual motility before bolus transfer

- overt signs of aspiration (coughing, throat clearing, shortness of breath)

- increased total swallow time (Nienstedt et al, 2018).

Some useful tools for early detection of swallowing problems are:

- swallowing disturbance questionnaire (SDQ) – considered a validated tool to detect early dysphagia in PwP; has good sensitivity (80.5%) and specificity (81.3) (Cohen and Manor, 2011). (See also EAT-10, Belafsky et al, 2008)

- swallowing clinical assessment score in Parkinson’s (SCAS-PD) – has high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (87.5%); detects clinical signs of aspiration with good agreement with VFSS (Branco et al, 2019)

- handheld cough testing (HCT) – a novel tool for cough assessment and dysphagia screening in Parkinson’s; identifies differences in cough airflow during reflex and voluntary cough tasks and screens for dysphagia in Parkinson’s with high sensitivity (90.9%) and specificity (80.0%) (Curtis and Troche, 2020).

A key issue when relying only on swallowing questionnaires is the validity and reliability of several existing clinical tools to detect Parkinson’s-related EDS difficulties. For example, some non-Parkinson-specific swallowing questionnaires were found to detect swallowing problems only in 12-27% of PwP, with less than 10% of PwP reporting spontaneously about dysphagia (Pflug et al, 2019; Buhman et al, 2019; Nienstedt et al, 2018).

Clinical bedside predictors of aspiration used for stroke, like the ‘normal’ water swallow test, have been shown to be unreliable in Parkinson’s. Maximum swallowing volume or the maximum swallowing speed were not a suitable screening instrument to predict aspiration in PwP (Buhmann et al, 2019).

Increased drooling (sialorrhea) was also deemed a sign of penetration or aspiration until Nienstedt and colleagues (2018) found that drooling cannot be considered an early sign of dysphagia. (See also Simons et al, 2014; Pflug et al, 2019.)

Early detection of swallowing problems using Parkinson-specific questionnaires and instrumental methods (FEES or VFS) is highly recommended.

Dystussia (impaired cough ability)

Another area of clinical and research significance is the impaired cough ability, due to lack of sensorimotor feedback (Curtis et al, 2024). Protecting the airway is crucial. The lack of sensory feedback from saliva and mucus that accumulates in the laryngeal vestibule should be addressed and assessed, not least because of the availability of effective treatments.

The rehabilitation of cough strength and effectiveness has been investigated recently using instrumental methods with good impact on reduction of aspiration/penetration risk (Troche et al, 2022).

Assessment of cough strength and effectiveness using a peak flow meter and understanding the level of sensorimotor feedback is highly recommended.

Medication and pill swallowing

Swallowing of medication is crucial for PwP but it can be affected by early and subtle EDS difficulties.

Repetitive tongue movements (such as ‘tongue pumping’) keep pills in the mouth for longer, which leads to a risk of them dissolving before they are swallowed. This risk is further increased by impaired tongue base retraction and pharyngeal residue, predominantly in the valleculae. Xerostomia (dry mouth) also increases oral retention time and pills can become stuck unnoticed in the pharynx or remain in the mouth (Warnecke et al, 2018).

Caregivers of PwP often modify oral medications by crushing or splitting tablets or opening the capsules. These practices can make it easier to administer the medication but are associated with an increased risk of medication administration errors (Patel, 2015). Therefore, before attempting splitting or crushing tablets, advice should be sought from the pharmacist or GP on alternatives.

Buhmann and colleagues (2019) studied which pills were easier to swallow using FEES. They found that almost half of the people with a substantially impaired ability to swallow a pill had no relevant problems with swallowing water. They concluded that testing pill swallowing, preferably using FEES, should be part of every swallow assessment.

Clearly there are more studies to be done on the type of pills that are easier to swallow, the links between pill-swallowing and response to medication and ways to deal with swallowing multiple pills.

Another issue reported recently is the effect of thickener on the pill bioavailability, ie the therapeutic properties of the pills (Patel, 2015). More studies need to be done specifically on parkinsonian medications (Atkin et al, 2024) in collaboration with pharmacists.

The manner and safety of swallowing medication should be assessed through direct questions, clinical observation and instrumental means. The link between timely intake of tablets and ability to swallow is particularly relevant to inpatient and outpatient care and it should be carefully considered.

Artificial nutrition and hydration

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a means of artificial enteral nutrition that can be considered when nutritional intake is expected to be qualitatively or quantitatively inadequate for a period exceeding two to three weeks. The effort required for eating and the time taken to feed during the day may be considerable, with each mouthful taking 12-15 times longer to chew and swallow. It is paramount to consider the clinical context, diagnosis, prognosis, ethical issues, anticipated effect on quality of life and the person’s wishes before proceeding (Sarkar et al, 2016). Another issue is post-insertion morbidity and mortality, which according to Sarkar (2016) can reach 88% of people.

Kobylecki et al (2024) analysed a cohort of people with atypical Parkinson’s and concluded that gastrostomy was performed relatively infrequently in this population.

To avoid such a high rate of complications teamwork between the neurologist and gastroenterologist/nutritional team and nutritional and swallowing assessment before and after PEG insertion are highly recommended. Communication between inpatient and outpatient care and of instructions is crucial. (See also Löser et al, 2005.)

Assessing sialorrhea

Quantification of saliva secretions is difficult, because many factors such as eating, talking and stress, as well as medication intake, can influence the production of saliva. Various methods have been used, including salivary glands scintigraphy, cannulation, open suction, spit collection and placing rolls of cotton in the mouth (Merello, 2008).

Sialorrhea-related discomfort or disability can be measured using specific scales, such as the ‘drooling severity and frequency scale’ (DSFS) and the drooling score (see ROMP-saliva, Kalf et al, 2007c), as well as the single item six on the activities of daily living section of the UPDRS. Direct observation of how PwP deal with secretions and the impact of dopaminergic medication and stimulation is necessary due to the impact on communication, swallowing and social interaction.

Communication interventions

Evidence around the use of different interventions to support people with Parkinsons who have communication difficulties is varied. A summary of randomised controlled trials for various communication interventions, which have been assessed using the GRADE method, is available through this link. The table is not exhaustive and is correct as of its date of publication.

LSVT LOUD

The only behavioural treatment with strong evidence in favour of its effectiveness in managing dysarthria is Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD) (Perry et al, 2024; Ramig et al, 2018).

LSVT LOUD is supported by 40 studies which tested the treatment using a wide variety of acoustic, perceptual, brain imaging, quality of life, stroboscopic, respiratory/kinematic and laryngeal/aerodynamic outcomes. Over 800 PwP and controls were examined.

LSVT LOUD is based on the principles of:

- voice focus

- intensive therapy (16 sessions over a month or two months)

- high effort

- calibration (person understanding the amount of effort needed to speak)

- salience-person focused.

There are three randomised controlled trials comparing LSVT LOUD to other intensive target therapies and one comparing the ‘standard NHS treatment’. Four studies examined the effects of LSVT LOUD in group therapy, with the remainder focusing on individual treatment. Most were delivered face-to-face, with five studies examining LSVT LOUD through telehealth. Patient-reported outcomes were analysed in 18 studies. In terms of intelligibility there were mixed results: eight studies reported improvement and two studies (Tripoliti et al, 2011; Theodoros et al, 2006) did not, depending on how intelligibility was measured (requests for repetition, ease of understanding or accuracy of listeners’ transcription of participants’ speech).

There are several studies evaluating the effectiveness of treatments based on loudness to a lesser or greater extent: Speak OUT! and the LOUD Crowd (a maintenance group run after initial therapy) (Behrman et al, 2020; Boutsen et al, 2018) target vocal function by prompting PwP to speak with intent. They are similar to LSVT LOUD in terms of hierarchical vocal tasks and intensity.

There is also a large amount of evidence on the delivery of LSVT LOUD through the internet, with positive outcomes (Theodoros et al, 2016).

Based on this evidence, LSVT LOUD is highly recommended for treatment of communication problems in PwP.

Singing

Music has been investigated as a treatment modality and found to be beneficial for vocal loudness and for swallowing difficulties in PWP (Tamplin et al, 2020, 2019). These two RCTs found significant improvement in vocal loudness for weekly singers and monthly singers compared to controls over 12 months. Singing participants also showed greater improvements in voice-related QoL and anxiety. Singing has also been shown to help with depression in caregivers (Tamplin et al, 2020). The same intervention did not reach significance when delivered online.

Based on this evidence, the use of singing groups is recommended for treatment of communication problems in PwP.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback (mainly through portable devices) has been investigated in three studies, involving in total 38 people. Two studies involved wearing a biofeedback device outside of the clinic with no in-person sessions.

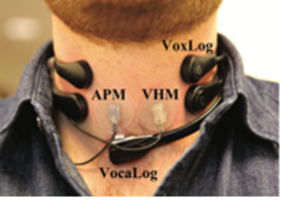

Figure 1: Optimal positioning of biofeedback device (Van Stan et al, 2014)

Two studies examined participants’ experiences with wearable biofeedback devices. Most found them easy to wear and reported that they served as a reminder to use a louder voice and to speak more often (Schalling et al, 2013). Some mentioned that the device felt uncomfortable and drew attention. The most common complaints were positioning the device, cord and microphone and planning outfits and hair that could accommodate the device.

Based on this limited evidence the use of biofeedback devices is recommended at an experimental level mainly as a ‘cue’ to increase vocal loudness.

Masking noise/SpeechVive/delayed auditory feedback

The effects of masking noise/SpeechVive on speech have been investigated in five studies including 100 participants. Four of the studies involved measuring the immediate effects of masking noise or multitalker babble and one study involved wearing a SpeechVive device over eight weeks.

Quedas et al (2007) measured voice outcomes related to the Lombart effect while white noise was presented at 40, 70 and 90 dB SPL. Results showed that as the masking intensity increased vocal intensity and frequency also increased.

Coutinho and Cangelosi (2009) examined the immediate effects of four listening conditions (habitual, delayed feedback (DAF), amplified feedback and masking noise) on auditory-perceptual voice features. Delayed feedback resulted in significantly worse vocal quality, pitch, strain, rate, articulation and loudness compared to masking noise.

Brendel et al (2004) investigated the effects of DAF and frequency-shifted feedback (FSF) on speech outcomes in 16 PwP. Intelligibility ratings were significantly lower despite the slower articulation rate.

Richardson et al (2014) measured the effects of the SpeechVive device over eight weeks. Speech intelligibility significantly increased from 93% to 98%.

Based on this limited evidence, the use of SpeechVive/delayed auditory feedback/masking noise is recommended at an experimental level to increase vocal loudness.

Group interventions

Diaféria et al (2017) investigated the effects of group dynamics/coaching strategies on voice and communication outcomes in PwP. The goal of the treatment was to promote self-awareness and self-development, improve self-esteem and share coping strategies. Results showed significant improvements in participants’ self-evaluation of their voice following four weeks of the experimental therapy, compared to ‘traditional’ speech therapy.

HI-Communication (Steurer et al, 2024) is a group-delivered treatment of intensive and high effort voice therapy, based on the principles of LSVT-LOUD and delivered as three sessions per week over 10 weeks. It showed positive results in its first randomised controlled trial but there are still further studies to conduct to refine the dosage and the type of intervention.

Based on this limited evidence the use of groups for therapy is recommended at an experimental level to increase social participation and vocal loudness.

Technology for treatment

A range of mobile phone applications (‘apps’) have been developed (Linares-Del Rey et al, 2019) to aid oral communication.

Many of these are useful, such as the text-to-speech conversion; others provide speech rehabilitation support.

However, the poor quality of the methodology of the studies involved in their validation (Linares-Del Rey et al, 2019) prevents us from recommending generalised use of these apps. The potential benefits and risks associated with mobile healthcare give rise to a need for official regulation and further research in the field. This would provide both healthcare professionals and PwP with safe, reliable tools for the care and management of their symptoms.

Communication partner training

Research recognises the need for interventions that involve both people living with Parkinson’s and their communication partners to improve communication (Thilakaratne et al, 2021).

Communication partner training can enhance functional communication and participation for people with communication difficulties (Simmons-Mackie et al, 2016) and improve the knowledge, communication skills and attitudes of communication partners. However, evidence is currently limited for people living with Parkinson’s. Whilst there is emerging evidence in this area (Clay et al, 2023), effectiveness remains to be proven.

The wider impact of this type of intervention in combatting the stigma from Parkinson’s and its communication difficulties can also be further investigated.

Acquired neurogenic stuttering (ANS)

Due to the lack of evidence (mainly case studies), management of ANS needs to be individualised. Delayed auditory feedback (DAF) has been used in a person with PSP (Hanson and Metter, 1980) to reduce speech rate, but it needs to be studied in larger populations to identify who can benefit.

External cueing (visual and auditory) (Park et al, 2014) has had a significant effect on both gait festination and speech. Pacing board (Helm, 1979) has been used with the same principle in a case study.

Rhythmic auditory stimulation has been used in PwP (Rösch et al, 2022) with intriguing results in both speech rate and cadence and velocity of gait; they found that speech/music work had a beneficial effect on gait and dancing had a beneficial effect on speech. These results need to be replicated in further studies. Rhythm in speech work can be enhanced through reading poetry. Music and singing have been used anecdotally.

Motor learning (over-practice of words/sentences) (Whitfield and Goberman, 2017) has been used for PwP but not in ANS with good results. Similarly, metronome cueing has been used again with PwP but not with ANS (Toyomura et al, 2015).

LSVT LOUD (Ramig et al, 2018), an intensive speech treatment targeting loudness, can be beneficial in cases of initiation problems due to reduced amplitude or it may not, in cases of severe ANS or other concomitant symptoms, such as dyskinesia or orofacial dystonia. There are no published cases of LSVT LOUD applied for ANS.

Due to the limited evidence, clinicians are encouraged to work based on the pathophysiology of stuttering and within a team to evaluate which strategies are beneficial. The high levels of anxiety of the PwP surrounding communication should be considered.

Swallowing interventions

Evidence around the use of different interventions to support PwP who have EDS difficulties is significant. A summary of randomised controlled trials for various interventions in EDS, which have been assessed using the GRADE method, is available via this link. The table is not exhaustive and is correct as of its date of publication.

A study of the validity of compensatory strategies (Logemann et al, 2008) found that the thickness of the bolus is more significant than postural adjustments (‘chin down’ manoeuvre) in preventing the incidence of aspiration in the largest sample to date of PwP (N=711). The study triggered a debate on the use of therapy strategies to reduce aspiration in PwP (Coyle et al, 2009).

The consensus in the recent literature seems to support an individualised approach to the management of EDS difficulties for PwP, with a ‘skill-versus-strength’ approach.

Electrical stimulation therapy

Electrical stimulation therapy has shown no significant difference in FEES and VF dysphagia severity ratings when compared to conventional dysphagia therapy (Baijens, 2012; Logemann et al, 2008).

Electrical stimulation therapy is not recommended for swallowing therapy in PwP.

Biofeedback

Video-assisted swallowing therapy (VAST) compared to conventional therapy showed a significant improvement in swallowing function from both interventions, with pharyngeal residue significantly better in the VAST group (Manor et al, 2013).

Providing feedback on individual swallowing function from VFS examination is highly recommended.

Expiratory muscle strength training

Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) aims to exercise the expiratory muscles and increase the hyolaryngeal movement that protects the airway from liquid or food penetration or aspiration. The EMST device is a calibrated, spring-loaded valve which mechanically overloads the expiratory and submental muscles. The PwP blows into the device with increasing resistance over time. It can improve submental muscle contraction, which helps to elevate the hyolaryngeal complex during swallowing and strengthen the protective cough.

When compared to a sham device EMST significantly improved PwP’s penetration-aspiration (PA) score (Troche et al, 2010).

Another study by the same group examined the effect of sensorimotor training for airway protection (SmTAP) using capsaicin and online visual feedback of peak flow to improve cough strength. When compared to EMST, SmTAP was found to be significantly more effective (Troche et al, 2022).

Expiratory muscle strength training and sensorimotor training for airway protection are highly recommended treatments for cough strength training in PwP.

Saliva interventions

Despite the frequency and related disability there are few proven effective treatments for sialorrhea in PwP. Pharmacological treatments aim to reduce the flow of saliva by blocking the cholinergic transmission that underlies the secretion of saliva. Behavioural treatments aim at retraining the frequency of swallow (McNaney et al, 2019; South et al, 2010) and the effectiveness of cough (Troche et al, 2022).

Pharmacological treatment

The 2019 Movement Disorder Society evidence-based review on therapies for non-motor symptoms recommended botulinum toxin (BonT) as clinically useful and glycopyrrolate as possibly useful for the treatment of sialorrhea in PwP (Seppi et al, 2019). However, BonT has some drawbacks; the most common side effect was dry mouth and dysphagia (Cardoso, 2018). It is also an invasive procedure and requires re-administration every few months by well-trained physicians with access to specialised monitoring techniques.

Mestre et al (2020) conducted a double-blinded placebo-controlled parallel-phase II study in PwP. The primary outcome was sialorrhea-related disability (Radboud Oral Motor Inventory for Parkinson’s Disease – Saliva) (Kalf et al, 2007c). Glycopyrrolate does not cross the blood-brain barrier and thus has less risk of neuropsychiatric effects. The study had a limited number of people (N=22 completing the study, no information on recruitment), with a significant effect on ROMP-saliva score for the treatment group at 12 weeks. Adverse effects included dry mouth and constipation.

Due to the above complications clinicians are advised to work in a team in order to facilitate pharmacological treatments and minimise complications.

Behavioural treatments

In spite of the very debilitating impact of drooling on quality of life, there are very few studies looking at behavioural treatments. Most studies applied treatments from stroke or cerebral palsy focused on reducing the flow of saliva as opposed to increasing the frequency of swallowing.

Oromotor therapy is the most useful nonsurgical option for people with sialorrhea but most of the evidence on the effectiveness of oromotor strategies (ie techniques that improve functional response, movement range and the strength of the articulators) has been studied in the paediatric population and not systematically studied in PwP (Limbrock et al, 1991).

Two studies have been conducted to investigate compliance with motor or tactile cues for PwP: Marks et al (2001) used a sound-emitting brooch and McNaney et al (2019) used a wristwatch to cue PwP to consciously swallow. Participants in both studies reported improvement in severity and frequency of sialorrhea and good acceptance of the cueing device.

More studies targeting cueing for saliva should be implemented.

In a similar study South et al (2010) used chewing gum for cueing of saliva swallowing in 20 people. They measured the changes in frequency and latency of saliva swallowing as measured physiologically. They found a strong link between spontaneous saliva swallowing and chewing gum and suggested that more research should concentrate on cost effective and self-managed approaches, without the inherent side effects of reducing salivary flow from pharmacological and neurosurgical approaches.

In summary, in spite of the very debilitating impact of drooling on quality of life, there are very few studies looking at behavioural treatments. Most studies applied treatments from stroke or cerebral palsy focused on reducing the flow of saliva as opposed to increasing the frequency of swallowing.

A logical next study would be on the effects of EMST training on the frequency and latency of saliva swallowing.

Cueing strategies (using auditory cues or chewing gum) to increase spontaneous swallowing of saliva are recommended for the management of sialorrhea in PwP.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

This is the most common type of atypical parkinsonism, about one tenth as common as Parkinson’s. PSP affects men and women equally. On average, PSP starts in a person’s early 60s. The cause of PSP is unknown. PSP is associated with accumulation of a protein in the brain called tau that clumps up in all cell types. The cause of this clumping is unknown. PSP is not usually considered hereditary. PSP is not spread from person to person and it has not been clearly associated with any environmental exposures.

Symptoms of PSP include the following:

- Early on, people with PSP often have trouble walking and balancing and may fall backwards, often many times a day. They tend to lurch/stagger and move quickly and impulsively. Some have problems walking where they feel like their feet are glued to the floor (a sensation of ‘freezing of gait’).

- Many people with PSP experience difficulty with eye movements. This makes reading difficult and may cause double vision. They can also have involuntary blinking or eye closing and difficulty opening the eyes (‘blepharospasm’). This might interfere with communication and reading.

- People with PSP may move slowly, which leads to them carrying out normal daily living activities slowly.

- People with PSP may experience stiffness, especially in the neck.

- Facial expressions may change. This is often characterised by staring ahead with raised eyebrows and a frown on the forehead.

- People with PSP can experience a hoarse, slurred, groaning voice along with swallowing difficulties.

- Some people with PSP may experience cognitive problems including loss of motivation and inhibition, emotional variability (pseudobulbar palsy) and dementia.

The condition varies from person to person. In some forms, freezing during walking and slowness of movement are the main features; in other forms, there are early tremor and features that look more like Parkinson’s. Where a PwP presents with early severe speech changes, this may indicate the presence of PSP.

PSP is diagnosed based on medical history and neurological examination. When the condition is just beginning, it may look similar to Parkinson’s, making diagnosis difficult. There is no blood or other test for PSP but sometimes a brain MRI may help make the diagnosis if it shows shrinking in the midbrain and frontal lobe areas.

PSP speech characteristics

A common initial manifestation of PSP (often within the first two years of diagnosis) is dysarthria. It is more frequent and more prevalent in PSP than in Parkinson’s. The symptoms of dysarthria associated with PSP are mixed: hypokinetic, spastic and ataxic symptoms are consistently identified, generally in that order of frequency. The combination of spastic, hypokinetic and ataxic components correlates with the loci of neuropathologic changes and recognising them is considered important for clinical diagnosis (Duffy, 2019).

Palilalia is also frequently noted and stuttering or echolalia are mentioned in some studies.

PSP eating, drinking and swallowing characteristics

Unlike PwP, people with PSP are often able to adequately perceive their symptoms of eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties. According to Warnecke et al (2010), endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in people with PSP showed that penetration/aspiration was more common with liquids than with semi-solids, especially in the initial stages (less than three years after diagnosis) with a pronounced premature spillage, a delayed swallowing reflex and residue in the valleculae and piriform sinuses.

Due to a disinhibited cough reflex, even small boluses that penetrate the laryngeal vestibule can trigger a long-lasting involuntary cough. This violent sustained coughing may give rise to a false impression of severe aspiration and may often result in a clinical overestimation of the dysphagia severity (clinical observation of the author and reported in Warnecke et al, 2018). A specific clinical test to distinguish PSP-related dysphagia does not exist.

PSP speech treatment

There are two issues that challenge the application of known speech treatments, such as LSVT LOUD, to people with PSP: the complexity of the vocal neuropathology and the variability of speech presentation. Speech impairment can be present in all people with PSP and much earlier on in the diagnosis. It is characterised by a harsh and strained voice quality and often palilalia on top of the monotonicity of the parkinsonian speech. Some ‘echolalia’ (for example, repetition of whole phrases) can also be present.

The largest study on speech treatment for people with PSP is by Sale et al (2015), who offered LSVT LOUD to 16 people with PSP and compared the effects with those seen in 23 PwP. They found significant increase in vocal loudness for all tasks, but they do not report on speech intelligibility.

One of the oldest case studies on treating the fast rate of speech and the lower vocal intensity in a person with PSP is by Hanson and Metter (1980). They used a delayed auditory feedback (DAF) device in order to slow the rate of speech and increase the loudness. It is one of the earliest studies to use a speech intelligibility rating to measure outcome. The speech rate of the person was at 282 words per minute (wpm), an ‘extraordinarily fast’ rate of speech (compared to the normative 160wpm), that was reduced to 124wpm with the DAF prosthesis.

SpeechVive is a recent development of the same principle of feedback. The variability of speech characteristics in people with PSP requires an equally diverse approach to treatment, with dynamic monitoring and prevention of total loss of voice or even ability to communicate by introducing alternative modes or voice banking as early as possible. There is an urgent need for further studies on overall management of the specific communication needs of people with PSP.

Swallowing treatment

When considering swallowing therapy in people with PSP the association of dysphagia with neurocognitive symptoms should be considered. Depending on the pathophysiology Warnecke et al (2018) reported that the most effective strategies for improving swallowing were: the chin-tuck manoeuvre in the event of premature spillage, effortful swallow to treat residue and dietary modifications (especially switching to soft or semi-solid food consistencies) to address penetration/aspiration.

Another area with significant evidence is the effect of sensorimotor training airway protection (smTAP) on cough outcomes. Borders et al (2022) showed that people with PSP are able to train their cough function to protect their airway. This feasibility study requires further research.

Cognitive decline, axial rigidity and retrocollis were associated with deterioration of dysphagia in PSP and were the highest risk factors for discontinuation of oral intake (Iwashita Y et al, 2023). Early identification and treatment of these factors could contribute to improvement of a person’s care and management of swallowing.

Multiple system atrophy (MSA)

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare disorder that affects the functioning of multiple systems in the brain. Some of these are involved in the control of movement, balance and coordination, while others maintain blood pressure and bladder, bowel and sexual function.

People with MSA may experience:

- slowness of movement, muscle stiffness and/or shaking/jerky movements

- problems with balance and coordination

- feelings of light-headedness or dizziness on standing

- problems controlling bladder function and constipation.

People with MSA may need more frequent and timely follow-ups due to the complex symptomatology and more rapid progression of the condition.

MSA speech characteristics

Dysarthria is quite common in people with MSA and it tends to emerge earlier than in Parkinson’s (within the first two years). It can be the presenting symptom.

Dysarthria is often mixed. Hypokinetic, ataxic and spastic types are common. Recognition of dysarthria types other than hypokinetic can help distinguish MSA from Parkinson’s (Rusz et al, 2019). Daoudi et al (2022) published a comprehensive study on the acoustic differences between Parkinson’s, PSP and MSA.

One of the distinguishing features of MSA is laryngeal stridor in as many as one third of people. This is a problem commonly associated with excessive snoring and sleep apnoea. Recognising stridor within various combinations of spastic, ataxic and hypokinetic dysarthria is diagnostically valuable.

Inhalatory stridor is traditionally thought to reflect abductor (posterior cricoarytenoid) laryngeal weakness, secondary to involvement of the nucleus ambiguous.

However, some study findings have suggested that in MSA, laryngeal dystonia may be the cause of stridor (Merlo et al, 2002; Isono et al, 2001). In addition, arytenoid tremor and myoclonic vocal fold movement (Gandor, 2020) may be seen in people with MSA as early as diagnosis, which could serve as a predictor of upper airway obstruction (Ozawa et al, 2010).

MSA eating, drinking and swallowing characteristics

There are two seminal articles on video-fluoroscopic swallowing studies (VFSS) data for people with MSA (Higo et al, 2003a; Higo et al, 2003b). The most frequent pathological findings were delayed oral bolus transport, insufficient movement of the tongue base, impaired oral bolus control and a slowed laryngeal elevation. In people with MSA with predominantly cerebellar signs delayed oral transfer caused by disturbed tongue coordination was predominant in the initial stages of the condition. People with MSA can also experience significantly more frequently impaired oesophageal transport with food stagnation. This can lead to food regurgitation and suffocation during nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, as a result of megaoesophagus (Taniguchi et al, 2015).

To avoid further dilation of the oesophagus, people with MSA should not lie down immediately after eating. Before initiating CPAP therapy, it is necessary to investigate whether megaoesophagus is present because therapy associated with aerophagia may induce regurgitation from the dilated oesophagus at night.

MSA communication treatment

Skrabal et al (2020) investigated the effect of a ‘clear speech’ (which they define as ‘hyperarticulation’) approach on three groups: 17 PwP, 17 people with PSP and 17 people with MSA. They found that during clear speech instructions PwP were able to improve loudness and pitch variability whereas people with PSP and MSA were able to modify only their articulation rate. That could be due to the ability of PwP to improve when cued externally, or the improvement in voice from dopaminergic therapy.

Sonoda et al (2021) investigated the impact of intensive speech therapy as part of inpatient rehabilitation on people with MSA-cerebellar. They worked five days per week over four weeks and involved articulation training, pitch and prosody work and ‘targeted explosive or scanning speech’. They used the Voice Handicap Index (VHI-10) to measure the impact of the 18 sessions and found significant improvement in the stress from conversation due to improvement in speech.

Cámara et al (2024) presented the results of a therapeutic education programme with caregivers consisting of eight 60-minute interdisciplinary sessions (sessions on orthostatic hypotension, speech therapy, gait and balance, psychological support, urinary dysfunction, occupational therapy and social support). They found that the significant difference in satisfaction across sessions was driven by higher scores in speech sessions. There was no significant worsening in any scale over six months.

Lowit et al (2025) published their RCT on treating people with MSA-cerebellar (MSA-C) with ‘ClearSpeechTogether’, a speech treatment based on clear speech instructions and intensive delivery via telehealth. Communication outcomes were mixed with communication confidence showing greater gains. The main outcome of the study was that people with MSA-C can benefit from speech therapy even with the rapid rate of their disease progression.

There is a pressing need for further studies on the management of communication difficulties in people with MSA, respecting the variability of their symptoms, the need to maintain communication ability and the creative use of technology. Fatigue during exercise should be taken into account when treating people with MSA.

MSA swallowing treatment

Specific therapeutic procedures do not exist yet for people with MSA-related dysphagia. Because people with MSA often have impaired vocal fold mobility (including paradoxical vocal fold movement) (Warnecke et al, 2019) or laryngeal dystonia with stridor, dysphagia therapy needs to target the coordination of swallowing and breathing (Warnecke et al, 2021).

People with difficulty swallowing pills should consult their GP/pharmacist before crushing/splitting tablets or considering other formats.

The discussion for alternative feeding should take place when it is clinically appropriate. This may be earlier in the disease process. Kobylecki et al (2024) analysed a cohort of people with atypical Parkinson’s and concluded that gastrostomy was performed relatively infrequently in this population.

To avoid such a high rate of complications teamwork between the neurologist and gastroenterologist/nutritional team and nutritional and swallowing assessment before and after PEG insertion are highly recommended. Communication between inpatient and outpatient care and of instructions is crucial (see also Löser et al, 2005).

Corticobasal syndrome (CBS)

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), also known as corticobasal syndrome (CBS), is a rare, progressive neurodegenerative disease with a wide variety of symptoms and signs. It was first identified in 1968. The disease CBS typically starts between the ages of 60 and 70 and usually affects one side of the body much more than the other.

Common symptoms of CBS include:

- slowing of movement and stiffness of the neck, arms and legs

- balance and walking problems, which may cause falls

- muscle twitches and jerks called myoclonus

- difficulty performing common arm movements

- loss of sensation on one side or trouble identifying things by touch

- a feeling that an arm has a mind of its own, sometimes called ‘alien limb’

- difficulties with speech and language, including trouble finding the right words, groping (signs of apraxia of speech) and occasionally reversing ‘yes’ and ‘no’

- behavioural changes such as loss of motivation or increased irritability, or personality changes.

The cause of CBS is unknown. As with PSP, CBS is associated with tau proteins in the brain. These are important for normal motor function but people with CBS have an abnormal tau protein which appears to damage nerve cells in certain areas. Researchers do not know why this protein is abnormal in CBS. CBS is not hereditary and it has not been linked to any environmental exposures.

Diagnosis of CBS is based on medical history and neurological examination. Since CBS signs may be similar to other conditions, such as Parkinson’s, it can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages. Scans such as MRIs are often useful and may rule out other conditions that mimic CBS.

Please note that although there is information on the speech and EDS characteristics of people with CBS, there is no specific research on successful interventions for speech and EDS difficulties. SLTs should apply caution when trialling interventions with this population. Research into this area is needed.

CBS speech characteristics