An overview of deafblindness, including definitions, impact on people’s lives and the role of speech and language therapy.

The page previously referred to ‘deafblindness’ as ‘multi-sensory impairment’.

Last updated: August 2021

If you’re a speech and language therapist, please sign up or log in to access the full version of this content.

Key points

- There are different words used to describe deafblindness. Deafblindness can also be called dual sensory loss, dual-sensory impairment or multi-sensory impairment.

- People with deafblindness are individuals. There are lots of differences in how deafblindness affects each person. Deafblind people have three things in common: difficulties with communication, accessing information about the world and moving around independently.

- Not all people with deafblindness identify as being deafblind. They may prefer to call themselves deaf people who can’t see very well; physically disabled people who can’t see or hear very well; older people who can’t see or hear as well as they used to; or something else.

- Children with deafblindness are a ‘low-incidence high-need’ group, this means there are not very many of them, but they often need a lot of support in school to learn and develop.

- There is a growing population of older people with age-related dual sensory loss (deafblindness).

- Local authorities have responsibilities (statutory duties) to identify, assess and provide support for deafblind people.

A note on terminology

This overview intends to use positive language about disability. Depending on the context, ‘person-first terms’ like ‘a person with CHARGE syndrome’ or ‘a person who is deafblind’ and ‘community-identifying terms’ like ‘Deafblind people’ are used. Sometimes a term is used because there is legal recognition or a reason in the context of a statutory policy.

Generally when writing about people who are deafblind, sentences can get long and clumsy to read. We have tried to strike a balance using positive terms and keeping things easy to read.

Phrases like dual sensory loss, dual sensory impairment or multi-sensory impairment are also used to describe problems with hearing and vision. In this overview the term deafblind is used.

We recommend that when speaking about a person or a group of people, and it is possible to check, you should always use the words that they are most comfortable and identify with.

If you have any feedback about terms used in these pages please contact us.

Key terms used in this information are defined in our guidance glossary.

What is deafblindness?

Deafblindness is when someone has a problem with both seeing and hearing. When someone has difficulty seeing or hearing clearly they can usually compensate with other senses. For example, to some extent, a deaf person can compensate using their vision and a blind person can compensate using their hearing.

When someone has problems with both hearing and vision, it makes it harder to compensate with the rest of the senses. This is known as deafblindness. Very rarely are deafblind people completely deaf and completely blind; most deafblind people have some hearing and/or vision.

Different people have different combinations of hearing and vision difficulty and there are four groups:

- People who are deaf but have some vision.

- People who are blind but have some hearing.

- People who have both some hearing and vision.

- People who are totally deaf and blind.

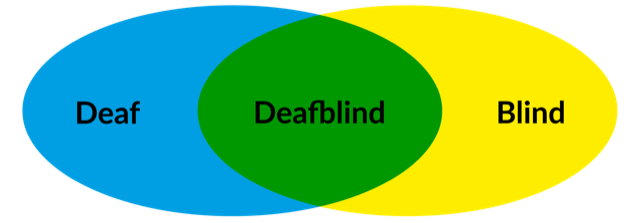

Deafblindness is a unique disability and is different to being blind or being deaf. Some people find it helpful to think about these differences similarly to mixing colours.

If deaf/hearing impaired is likened to the colour blue, and blind/vision impaired is likened to the colour yellow. When mixed together they don’t make a bluey-yellow (someone who is mostly deaf but doesn’t see so well) or a yellowish-blue (a person who is mostly blind and can’t hear as much), but they make a whole new colour in itself, green (someone who is deafblind).

Deafblindness is the same, a whole new and unique disability which needs its own way of thinking about support, solving problems and making a difference to people’s lives.

Everyone who has deafblindness experiences difficulties with getting access to information about the world, communicating with other people and moving about as independently as possible.

Causes of deafblindness

There are lots of causes of deafblindness. Some people are born deafblind, before they have learnt language (this is called congenitally deafblind). For many people who are born deafblind the cause of their deafblindness is unknown. Other people develop deafblindness as they get older and some people have deafblindness as a result of an illness or accident (both of these are called acquired deafblind). Most people with deafblindness are older people with changes to their hearing and vision as they age.

There are lots of causes that people are born with as a result of complications at birth or because of changes in their genes. Common syndromes, caused by these gene changes include Usher Syndrome, CHARGE Syndrome, and Down’s syndrome.

It has been estimated that there are 440,000 people with deafblindness in the UK; of these 23,000 are estimated to be children (Robertson and Emerson, 2010). Worldwide it is estimated that deafblind people make up between 0.2 and 2.0% of the population (World Federation of the Deafblind, 2018).

Children who are deafblind are sometimes called a ‘low-incidence, high-needs’ group by school administrators. This means there are not very many of them, but they often need a lot of support in school to learn and develop. This is an educational term, designed to help identify children who need support. As these children get older their needs often remain the same into adulthood.

There is a growing population of older people with age-related dual sensory loss (deafblindness). Not everyone identifies as being deafblind and may prefer to be called something else. Other words for describing deafblindness include dual sensory loss, dual-sensory impairment or multi-sensory impairment.

The impact on people’s lives

The senses and how they work

Most of us are taught about the five senses at school, hearing, vision, touch, taste and smell. There are more senses which have a role in how our bodies work.

Senses that are less often known are:

- The vestibular sense (balance).

- The proprioceptive sense (awareness of the body in space).

- The interoceptive senses (this includes internal feelings like pain, hunger, feeling full or needing the toilet).

At the most basic level senses are input-process-output systems:

- Input: Something that we see, hear or feel causes a sense receptor to be stimulated which then sends signals to the brain.

- Process: Recognition of sensory signals are processed and sensory information is organised, interpreted, prioritised, stored and compared to previous experiences.

- Output is a little more complicated, in that they can stimulate:

- A movement response such as a reflex or planned action.

- Integration with other sensory information to generate a behaviour, thought or emotion.

- Filter out unnecessary information or help us to focus where additional information is needed, this helps us to attend and concentrate.

The central nervous system supports the senses and in turn the senses allow us to develop our physical, thinking and problem solving skills.

For more information about how hearing and vision work see our deafness and visual impairment pages.

See this short video which explains our senses and how they work together.

Access to information

Understanding the world as a deafblind person

A person who is born deafblind understands the world differently because of the different way that information arrives through vision and hearing. Vision and hearing are the two distance senses that give us information about what is happening around us. It can be difficult for people with deafblindness to compensate for the loss of one distance sense with another, and they will have to also use other senses to get the same information. These other senses are:

- touch (haptic)

- body awareness in space (proprioception)

- balance (vestibular)

- smell

- taste

- internal states and sensations (interoception)

Three senses work together to help us stay upright and balanced. Together they are known as the triad of equilibrium. They mean that we can sit and stand independently and keep upright, even if the environment changes or is unstable.

- The visual system provides information about where we are in the world, in relation to straight and upright markers around us.

- The vestibular system tells the body about its position as it moves and changes position in space.

- The proprioceptive system gives the body feedback about the position of joints and muscles in the body.

Without access to this information it means deafblind people can feel unstable and insecure. It means they may have to focus on being grounded and stable before they can use their senses well.

People with deafblindness will also need to rely upon their sense of touch to find out more than they can using hearing or vision alone. Deafblind people can feel tired more often than others because it is harder work and takes longer when using their remaining senses or using touch to access information.

Ways of learning

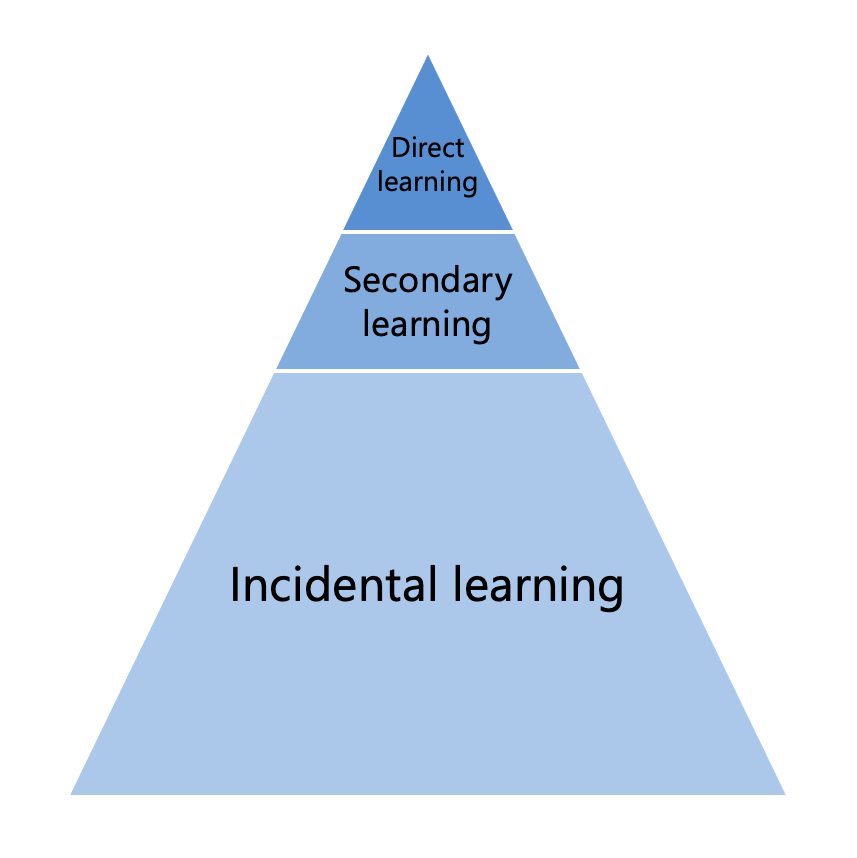

There are three ways of learning that are available to children who can see and hear:

- Direct learning is what you would experience in a practical activity and includes hands-on experiences. Over the lifetime of learning, these experiences account for a relatively small amount of learning.

- Secondary learning is what you experience in a lecture or presentation. Learning occurs through listening to someone teach on a topic and share information. In terms of overall learning, secondary learning accounts for more than direct experiences.

- Incidental learning occurs in most daily experiences. Learning happens naturally and automatically in response to the constant flow of sensory information available to us. Incidental learning occurs automatically and typically makes up the most of overall learning.

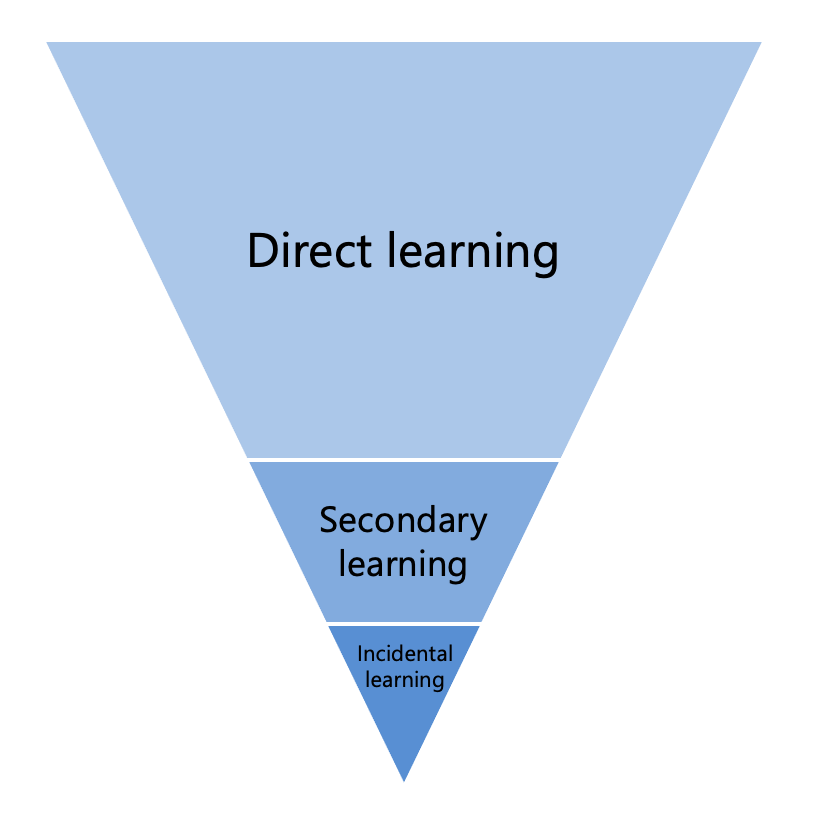

The opportunity to pick up information using incidental learning is very limited for deafblind persons, so the learning triangle becomes inverted. The typical way of learning does not occur naturally and needs to be supported through direct learning.

- Direct learning, as expected, is essential to provide hands-on experiences for learning. Direct learning is considered by far the best way for children who are deafblind to learn about the world.

- Secondary learning can be much harder as there are barriers to accessing auditory and visual information in real time.

- Incidental learning may often be missed because of the lack of access to visual and auditory information. It does not occur in the same way as it does for sighted-hearing children.

(Alsop et al, 2012)

Hearing technology and low vision aids

Hearing aids, cochlear implants, glasses and low vision aids all have a role to play to provide the best access to hearing and vision. For more information about these, please see our information about deafness and visual impairment.

Communication

People with deafblindness communicate in lots of different ways. Deafblindness can make some ways of communicating difficult. When choosing the best way to communicate, the decision should involve the person with deafblindness and build on their strengths and/or preferences.

The person may need different ways to communicate depending on the situation and how they are feeling at a moment in time. All ways of communicating should be accepted and supported.

A deaf person might be able to lip-read or use sign language, a deafblind person might not or might only be able to in certain lighting conditions or when their partner is standing at a certain distance.

The way of communication used will depend on the amount of sight and hearing, as well as any additional needs the individual has. Communication choices may also depend on when the person became deafblind and whether they have already learned formal language before becoming deafblind.

Some deafblind people will require British Sign Language (BSL) interpreters with additional skills. This can include BSL interpreters who use visual frame or hands-on BSL, deafblind manual interpreters or tactile sign language.

Some deafblind people will be able to lip-read, but might require good lighting and to sit right opposite the person who is speaking or be closer to them to be able to see. Some deafblind people will be able to use clear speech.

Many deafblind people who are born deafblind use different ways of communicating (known as augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems. These can include symbol systems, objects of reference, Voice Out-put Communication Aids (VOCAs) or other individual ways of communication, including bodily-tactile communication. AAC systems can be useful if used in a sequence to give the person a sense of what will be happening over time. See ways of communicating with deafblind people and RCSLT augmentative and alternative communication guidance.

Children with deafblindness usually need extra support to develop their learning and communication skills. Their development may be slower than children with sight and hearing or children with other disabilities. Children need to develop awareness of themselves, how they relate to other people and the impact their actions have on others. Difficulties seeing and hearing can make learning these stages difficult. Children are more likely to use different ways of communication (AAC) as well as rely on tactile communication, including bodily-tactile and hand-under-hand/tactile signing. It is important to consider the range of communication systems that work best for each child at the right time in their development.

Hand-over-hand guidance can be detrimental to the development of independence and can lead to hand withdrawal, the opposite of the intended support. Hand-under-hand exploration and support is a more respectful way to share exploration and leads to active touch development.

Some deafblind people have specialist support workers to help them with communication, mobility and in some cases independence and learning. Communicator Guides, Communication Support Workers or Intervenors can provide valuable individual support for people with deafblindness.

Mobility

Deafblindness can affect how a person moves around safely on their own. Sight and hearing help us to find out about the world and move around it safely. Without sight and hearing it can be hard to know where you are, and if there are any dangers present. If you are unable to access speech sounds it is difficult to hear verbal instructions of where to go and when to spot hazards.

Mobility (rehabilitation) or habilitation specialists are specialist workers who are trained to support the independent orientation and mobility of blind and deafblind people. Some deafblind people are able to use mobility aids, while others will require human support to navigate around. Mobility aids could include guide dogs or a red and white cane (a red and white cane is different to a white cane as the red stripes show other people that the owner is deafblind).

Many deafblind people will need training from a mobility or habilitation specialist in guiding, orientation and mobility techniques. An important area of development is the careful teaching of language used to describe location concepts.

People with deafblindness can learn to move around their environments with support. They need specialist support (often provided by advisory teachers and habilitation specialists) to teach strategies and to motivate them to move around as independently as possible in familiar settings.

Vision and hearing impairments should be considered together to make an accurate assessment of a person’s ability to navigate around. If vision and hearing impairments are considered separately a person’s ability to navigate around could easily be overestimated.

Walking may be tiring for an individual who is deafblind. Transitioning from one place to another may require additional effort due to the visual and hearing impairment as well as the need to use other senses. This can impact on their ability to engage with others or the ability to absorb information following this.

It is important to consider and to know how this will impact on the individual when delivering interventions. Individuals may need time to rest, process information or regulate their sensory system after a period of movement.

Some people also have physical needs and will require a wheelchair to move around. Consideration to level access and how to provide information and cues about what is about to happen for wheelchair users (eg turning left or right) may also be needed.

How can speech and language therapy help?

Speech and language therapists have a central role in providing individualised assessment, diagnosis and intervention to the child in partnership with their family or individual with deafblindness. This should reflect the individual choices made, regarding communication mode and (re)habilitation approach.

SLTs can work across a number of different settings such as:

- People’s homes

- Community health centres

- School and educational environments (nurseries, mainstream and special schools, colleges etc)

- Supported living, residential and care homes

- Hospital and specialist services (hearing implant centres, specialist clinics)

SLTs are essential members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) working with people who are deafblind. They can be responsible for:

- Carrying out specialist assessments and supporting diagnosis.

- Delivering appropriate intervention, therapy and training.

- Informing and supporting choices, for example, about technology or communication.

- Identifying the need for support from one to one services (like intervenors or communication support workers).

- Ensuring individuals are connected to services supporting their current needs.

There are currently no national competencies for SLTs working with people who are deafblind. Many therapists supporting people who are deafblind will have a core skill set within another field of speech and language therapy (eg complex needs, AAC or neurology). SLTs should consult RCSLT member guidance, and specialist SLTs or RCSLT clinical advisors when in need of further information or advice.

Specialist SLTs working with individuals who are deafblind are expected to have specialist postgraduate training, skills and experience.

SLTs working with individuals who are deafblind should:

- Have a specialist knowledge of:

- How the senses work and work together.

- Visual and auditory testing.

- The impact sensory impairment has on development and independence relating to communication and eating and drinking.

- Spoken and signed languages, including those specifically applicable to the tactile modality.

- Communication choices and strategies, including augmentative and alternative communication (AAC).

- Available hearing and vision technology and treatment.

- Different assessment options, including the extent to which assessment tools rely on hearing and/or vision and how this affects interpretation as well as tools specific for the population.

- Different intervention options, including how bodily-tactile communication emerges and develops in a person born deafblind and communication transitions, such as to tactile sign language for people who become deafblind.

- Current research evidence for this population and its application for service improvement

- Understanding of health and care policy and duties relevant to deafblind persons (such as the Deafblind guidance and relevant teaching regulations).

- Be skilled in contributing to differential diagnosis assessment.

- Be skilled in liaising with parents, families and other professionals and confident in working within the context of a multidisciplinary team, particularly with specialist teachers, deafblind specialist workers or consultants, intervenors, or other 1:1 support roles, with an understanding of boundaries between roles.

- Be skilled in the facilitation of person-centred decisions and consider the impact on families and other key relationships, particularly at key points of transition to new services.

- Have considerable postgraduate experience and receive appropriate postgraduate training and supervision to enable them to develop specialist knowledge and skills in this area. Funding should be made available to support this. Ongoing CPD is mandatory for all HCPC registered SLTs.

- Receive regular clinical supervision.

- Provide competency training and clinical support to other SLTs to develop their skills.

- Provide training and education to individuals who are deafblind, their families and others which will help to raise awareness of the value and impact of speech and language therapy in a multidisciplinary context.

- Be involved in wider strategic discussions to support plans for future service provision as clinical demands change and new technologies emerge.

Ways of communicating with deafblind people

People with deafblindness will access a wide range of ways of communication depending on their useful vision and hearing, preferences and needs.

Ways of communication may include:

Interaction

- Actions on other people or the world (some people might call this behaviour)

- Mood

- Intensive interaction

Manual sign language

- Close signing

- Sign language – key word signing or British Sign Language

- Tracking

- Visual frame

Speech

- Clear speech

- Lip reading

- Speech

- Tadoma method

Symbols

- Objects – as cues, objects of reference, calendars

- Photographs – as cues or core vocabularies

- Picture symbols – as single symbols, core boards, communication books

- Tangible symbols – as single symbols, calendars

Tactile

- Bodily-tactile communication

- Deafblind bock alphabet

- Deafblind manual alphabet

- Social haptic communication

- Tactile sign – accessing key word signing or sign language (hand-under-hand/hands on)

- Touch cues and on body signs

Technology and high tech AAC

- Switches

- Voice output communication aids (VOCAs)

Text

- Braille

- Large print

- Moon

- Speech to text

Ways of communication that are more specific to deafblind people are briefly described below.

Manual sign language

British Sign Language (BSL) is the naturally occurring language of the Deaf community. Officially recognised in 2003, there are 151,000 estimated BSL users in the UK (British Deaf Association, 2018).

Key word sign approaches including Makaton and Signalong. These signs have been based on and modified or simplified for people with learning disabilities and are used alongside speech to support communication.

British Sign Language and key word signs are both manual sign languages. Deafblind people with sufficient vision may well access manual signs without adaptations.

Some deafblind people may adopt the following adaptations:

- Visual frame – where signs are produced within an agreed signing space.

- Close sign – where signs are produced at an agreed distance.

- Manual signs may also be ‘tracked’ whereby the listener rests their hand on the signer’s wrist to follow the motion and keep signs within the preferred visual field.

These particular strategies may be useful to people who are first language BSL/keyword signing users and experiencing vision changes in a transition to tactile signing.

Tadoma method

Tadoma method is an oral language support method, where the deafblind person places their hand on the speaker’s throat and feels the movement and vibrations to help discriminate speech sound patterns (Reed, 1996).

The thumb is placed on the speaker’s lips, the fingers fan across the cheek and jaw and the little finger rests on the larynx. It allows for the detection of airflow, lip rounding and positions, jaw opening, voicing and resonance qualities.

Symbols: object cues and objects of reference

Object cues and objects of reference are widely used within special school and learning disability services. Objects of reference were first described as an intervention approach to support people with deafblindness and then became more widely adopted for people with a range of needs (McLarty, 1997; Ockleford, 2002).

Objects of reference have wide reach and use, but a very limited evidence base. They identified that practitioners use them a lot (up to 70%) although there is a huge disparity in parent/home use (Goldbart and Caton, 2010).

Practice around object cues and objects of reference is embedded in the symbolic hierarchy approach and different stages of using objects can include:

- Object cue: object is used to cue the person into what is about to happen

- Object assembly: object is used in some way as an integral part of the event

- Object or reference: object is shown as a precursor, but the object is specifically symbolic and not used in the activity

- Abstract object symbol: a part of an object is used as the referent. These objects are seen as a transition into using a symbolic system (and may perform the same role as tactile/tangible symbols)

Symbols: tactile symbols/tangible symbols

Tactile symbols and tangible symbols are subtly different modes of communication which have the potential to overlap depending on where in the world you are.

Tactile symbols are used similarly as visual symbols are used for sighted people. They are often parts of objects, but may include a whole object, attached to a background. They are considered a stepping-stone towards or an alternative to Braille (Hendrickson and McLinden, 1996). This tends to be a UK term.

Tangible symbols are tactile symbols that share a perceptual relationship with what they represent. They are tactile, but can also include photos or imagery. Tangible symbols are able to be manipulated in some way (Rowland and Schweigert, 2000). This tends to be a US term.

Tactile: bodily-tactile communication

Bodily-tactile communication is a term that recognises that before a shared tactile sign language is established people have access to a means to communicate through touch. It often continues to have a role to play after language is established.

Bodily-tactile communication takes account of the primary role that shared touch and motion have for deafblind infants to build attachment, establish joint attention and communicate. Touch is an integral part of this method of communication, but it is more than touch focused on the hands or tactile signing access method.

Bodily-tactile communication involves the bodily experience in a physical world, maintenance of contact and connectedness through touch. It allows experiences that are embodied within the body itself to be expressed through tactile memories, idiosyncratic actions and movements (Costain Schou et al, 2017; Nafstad and Rødbroe, 2013).

Bodily tactile communication may always be the main way for some people with deafblindness to communicate. Even if formal language is established, the deafblind person will still continue to experience the world through the bodily tactile modality. They may also continue to develop idiosyncratic signs through their bodily tactile experience of the world and these signs may develop and be used alongside a more formal cultural sign language.

In some cases a shared tactile sign language (in the formal sense of language with a recognisable grammar and syntax) may not develop. Communication may remain individual in which case good liaison between all involved in the care of the deafblind person is absolutely vital. This is particularly true of people with congenital deafblindness.

Tactile: social haptic communication (haptics)

Social haptic communication is a series of quick social messages which are used as a two way communication. They involve a series of touch cues (such as tapping the arm or leg, to indicate agreement) or drawing details onto a part of the body (such as the number of people sitting around the table drawn on the back. Social haptics give a broad perspective of what is happening and support both access to incidental information and quick self-expression (Palmer, 2018).

Tactile: tactile manual sign language

Tactile manual sign language is the adaptation of manual sign language into the tactile modality. In simple terms, signs are felt by the listener who places their hands on top of the hands of the speaker. Turns are regulated through the alternation of hand positions. Signing in this way may be referred to as tactile sign language or hands-on signing (NatSIP, 2019).

Tactile sign language can be used with all manual sign language, including BSL and key-word signing approaches.

There are two alphabet systems that can be used with tactile sign language:

- The block alphabet – where capital letters are traced into the palm of the hand in a specific manner.

- The deafblind manual alphabet – an adapted version of the two handed manual alphabet, where handshapes are produced in/on the listener’s hand.

Watch a video about the manual and block alphabets.

Tactile: touch cues and on body signs

Touch cues are consistent touch contacts on the body to alert and signal information to the individual. They are commonly adopted with people at an early stage of communication development. They are integral to routines and alerting and cueing. There are some standardised touch cue systems available.

On body signs are similar to touch cues, in that contacts are made consistently on the body, however there is the scope that on body signs could be used expressively as well as receptively.

- A number of special schools have developed core touch cues

- TaSSELS is a set of standardised touch cues with over 100 suggested cues

- Canaan-Barrie ‘on body’ signs (PDF) are an adapted on body key-word signs

Communication through touch should always be respectful and considerate, including seeking the person’s permission and taking account of cultural values. See our diversity, inclusion and anti-racism resources.

Text

Access to the printed word can be modified to enable access to information, develop literacy as well as support other communication systems (eg labels alongside tactile symbols).

Alternatives to standard print include:

- Large print whereby print is reproduced at the ideal font size and spacing to aid easy reading. It may be a case of enlarging the font, bold as well as considering line and character spacing. Some people find changes to the colour of paper and contrast with text aids access.

- Braille is an embossed print based on arrangements of six raised dots within cells. In the UK Unified English Braille (UEB) is the current standard. There are 1:1 corresponding alpha-numeric characters and signifiers (Grade 1) as well as contractions of letter combinations and short words (Grade 2).

- Braille can be produced on paper using a Perkins Brailler or Braille embosser, or there are technological alternatives such as ‘refreshable Braille displays’ or a ‘Braille-note’ to produce Braille.

- Moon is a system of tactile shape forms which are similar but not identical to the alphabetic form. Because of the closer associations with the alphabet, Moon is considered easier to learn for people with existing alphabet knowledge.

- Speech to text (STT) is when a palantypist (also called a speech to text reporter, STTR) types word for word what is spoken onto a screen which is read by the person. This method of communication is often used by people who are deaf particularly in meetings and presentations. Deafblind individuals may have specific large print or contrast preferences which aid their ability to read text from the screen.

Technology and high tech AAC: switches and voice output communication aids

As technology evolves it is becoming more accessible for those with sensory impairment. This type of communication system was rarely considered for those with visual, hearing or dual sensory loss due to the need to attend to visual or auditory information. There is a limited published evidence base at present however there have been examples of successful implementation through clinical work. Some technology may need adapting in order for it to be accessible to individuals, for example, using textures for differentiation of switches.

The limited research studies that have been reported indicate that switches, texture symbols and voice output communication aids have been used amongst the range of communication methods (Sigafoos et al, 2008).

Message switches can be used to express single words or simple phrases. These can be used independently or a number of switches with different messages presented as a ‘board’.

Studies have used message switches to gain attention, gain auditory output and to make choices (Mathy-Laikko et al, 1989; Schweigert, 1989; Schweigert and Rowland, 1992). These studies focused on single requests; however, interventions using technology, particularly high tech AAC should be considered for those that present with appropriate cognition and a desire to communicate with others. High tech devices using complex software have been successful in some clinical cases.

There is an emerging role for adopting a language and motor planning (LAMP) approach to support motor learning and development of AAC use for people with deafblindness. The consistent positioning of switches for items etc can enable a learner to use motor planning to make requests and develop a communication system using this method.

An assistive technologist is a helpful co-worker to establish technology for communication and environmental control.

For more information about supporting people using AAC see augmentative and alternative communication.

What can you expect from speech and language therapy?

SLTs are highly specialist and have extensive training and skills. They can play a vital role in supporting deafblind individuals.

There aren’t currently any UK-wide competencies relating to the role of the SLT in working with deafblind people. But there is clinical guidance for therapists about the knowledge, skills and experience they should have to provide effective support and services.

The following information is intended as a guide only and includes some common activities that SLTs may be involved in the context of a general pathway. Please note, these are only suggestions and specific support will be designed for individuals depending on their needs.

Accessible Information Standard

The Accessible Information Standard (AIS) was introduced in 2016. It aims to make health and social care information accessible to all people with a disability or sensory loss.

All services that provide NHS care or treatment, (including independent providers of NHS services), adult social care (including social services) and public health services must follow the AIS.

Services must:

- Ask you if you have any information or communication needs, and ask you how to meet them.

- Record your information and communication needs clearly, and in a set way.

- Highlight (or flag) your needs in your file or notes, so it is clear what your needs are and how to meet them.

- With your permission or consent and when appropriate, share your information and communication needs with other services; like other providers of NHS and adult social care.

- Take action to make sure you receive information you can access and understand, and receive communication support if you need it.

The sorts of changes you might find are:

- Sharing information in different formats like large print, Braille, electronic (eg email) and audio formats.

- Communication support such as a BSL interpreter. (The AIS requires that services can only provide registered qualified interpreters).

- Offer longer appointments.

- Make communication tools or aids available, such as loop systems.

- Provide support from an advocate if you need support to express your wishes.

- Provide alternative information and communication support when needed by a carer or parent.

- Being able to contact, and be contacted by, services in accessible ways, for example via email or text message.

More information about the Accessible Information Standard is available in this video by NHS England.

Identification and referral

If you have difficulties with both hearing and vision you are likely to access a team of professionals with specific roles to support you. You may not automatically be referred to a speech and language therapist. If you have particular questions or concerns about communication or eating and drinking you should be able to ask for a referral or self-refer to your local speech and language therapy service.

Assessment

The SLT will carry out comprehensive assessment in order to identify language development and areas of difficulty for the individual. They will assess how this impacts on:

- Communication

- Education and employment

- Social participation

- Wellbeing

SLTs can also assess eating and drinking skills if there are concerns in this area – see our information about dysphagia.

Deafblind people are unlikely to show their best skills and abilities on formal assessments which are based on the achievements of people with hearing and vision. You should expect your therapist to adopt a person-centred and holistic approach to assessment. This will involve working as part of a team, making observations, having discussions, direct working and adapting assessment where needed.

SLTs may identify the need for and/or assess you as part of statutory assessment processes; such as Education Health and Care Planning (EHCP), Mental Capacity Assessments and Continuing Care or Care planning assessments. When this happens assessment pathways should be adapted to provide sufficient time for information gathering, holistic observation, accessibility adaptations and multidisciplinary integration of findings.

One of the SLT’s roles that you might find most helpful is choosing the most appropriate way to communicate. You should be involved in this decision and your strengths and preferences taken into account when choosing how to communicate. SLTs may also work as part of a team to help diagnose other conditions individuals have, alongside deafblindness (examples include language disorder, autism, or swallowing difficulties).

Therapy and intervention

The SLT will work with the individual and when appropriate family or support circles to identify individual communication and personal goals. They will develop strategies and programmes of therapy to support you to achieve goals as appropriate.

Therapy can focus on lots of different things and some examples are:

- Facilitating parent-child interaction

- Facilitating communication development

- Facilitating language acquisition

- Facilitating speech development

- Assessing and facilitating social communication skills

- Facilitating communication in different situations with different communication partners

- Managing specific speech, language and communication difficulties that exist over and above being deafblind

The SLT will also advocate for all deafblind people who require access to sign language in order to communicate at their fullest potential if required.

Most of the time deafblind people have people who know them well and offer 1:1 support. This may be in the form of a family member, partner or as a paid worker; such as an intervenor, communicator guide, support worker or sighted guide. It would be expected that these key people who provide 1:1 support are included in the development and delivery of therapy and intervention.

Very often, the SLT will work in an advisory way so that therapy and intervention can be carried out across the day and in a wide variety of situations. This also means that for deafblind people who need trusted support, they maintain consistency with their 1:1 support. Sometimes SLTs will work directly to teach skills to the deafblind person. The SLT has a role to train key people so that they are competent communication partners to support the deafblind person.

The SLT will regularly monitor progress in development and achievement of goals. If necessary they will change therapy plans and approaches. As deafblindness is usually lifelong, people may access speech and language therapy services at different times during their life if appropriate.

Discharge

As deafblindness is usually lifelong, people may access speech and language therapy services at different times during their life if appropriate.

Some people may need short periods of therapy at times of change in their sensory or communicative abilities or change of services. Others may continue to develop over a long period of time. Discharge should not be automatic at the end of school or transition to adult services as some deafblind people have reached a stage in development when they can continue to make good use of therapy and intervention.

If you are going to be discharged from speech and language therapy this should be discussed in advance.

Discharge should only be considered when the person has access to information and communication within a supportive environment and has reached communicative potential.

Individuals, families and services should have the opportunity to re-access therapy should circumstances change.

Statutory deafblind guidance assessment

The deafblind guidance places specific duties on local authorities to identify, assess and provide services for deafblind people. Learn more about deafblind guidance assessment.

SLTs can be involved in undertaking a statutory deafblind guidance assessment under the relevant social care frameworks in England and Wales in a number of ways.

Depending on the circumstances and the level of experience and skill, SLTs may:

- Raise awareness of and identify the need for a deafblind guidance assessment to help meet a person’s social care needs.

- Contribute towards an assessment coordinated or undertaken by a suitably qualified person to complete care assessment and planning.

- Lead an assessment when communication is a key factor, working with the social care team to complete care assessment and planning.

Deafblind awareness

There are some simple strategies which can make a world of difference to welcoming, working with and supporting deafblind people. Like all people, deafblind people are individuals and have different needs and preferences. These are general guidelines which can help. Some suggestions are more important for some people than others depending on their levels of hearing and vision and how they communicate.

Making contact

- If you have not met the deafblind person before, find out about their preferred and best ways of approaching or communicating in advance of meeting them or ask them and their 1:1 support when they arrive.

- Try and find out if the person has better hearing or vision on a particular side and always locate yourself to that side.

- As you approach a person, try to approach from the front so that if they have vision they can see you coming (unless you know otherwise about their best field of vision). They may sense your approach as movement or vibrations.

- Make sure you have the person’s attention before talking to them (attention sharing can look different to what you expect from hearing/sighted people). You may need to gently touch their upper arm or shoulder to let them know you are waiting to speak to them. If the person has their hands full or is in the middle of something they may need some time to organise themselves before talking to you. Give them time once they know you are there.

- Communication can take place in close contact – touch and tactile contact is an important part of communication for deafblind people. Even with social distancing restrictions, deafblind people have a right to access communication in an accessible way. Interactions should be managed following appropriate clinical hand hygiene (consider washing, hand and nail care, jewellery) and safe COVID-19 working practices.

- Talk about tactile contact and agree on safe places to touch. Usually the hands, upper arms, shoulders and outer thighs are considered safe areas for tactile communication. It’s always best to ask rather than grab, and agree where you are both comfortable making contact; even if you are not sure someone will understand you.

- Think about what you wear – this is particularly important for people who use sign language as it can be difficult to make out hand shapes against a busy pattern. Plain and contrasting clothes can help the deafblind person identify who you are, follow gestures, and understand signs. Remember to pay attention to the background as well as clothes.

- If you are calling a deafblind person from a waiting room, remember they may not hear you call their name and you may need to approach them to make direct contact.

Communication

- Face each other and use good lighting. Try to position yourself so that light sources shine onto you rather than from behind you. Having access to portable lighting can help provide even lighting in dim settings.

- Turn off or minimise background noise where possible. Don’t be afraid to repeat yourself or find another way to communicate if you are in a noisy situation.

- Identify yourself at the beginning of an interaction – you might introduce yourself by using your name, sign or personal object to signify who you are (a personal identifier).

- Speak clearly – pay attention to how loudly you speak. You may need to speak slightly louder, but not too loud. Try not to distort your natural lip patterns if someone relies on lipreading.

- Pace communication – find the right pace that you can both follow. Remember that it can take longer to follow and process the message but it also gets easier the more you get to know each other.

- Communicate with respect; but you may also need to be direct to avoid ambiguity. If your tone of voice changes the meaning of your message you may need to explain that you are joking or what you really mean.

- You may also need to explain some things that are happening in the room so that the person can keep up with what is happening. For example, if someone discreetly enters or leaves the person may not notice – it’s about giving everyone equal access to what is happening. Likewise it is helpful to state where information is coming from – if you receive a relevant message on your phone, state the source of information aloud “I know Gwyn is running late because she just texted me”.

- Let the person know that you are listening – deafblind people may not be able to pick up on non verbal information that shows you are listening (like nodding your head, agreeing or smiling). Let them know what you have understood, you may confirm in a tactile way – tapping their hand, arm. For people who don’t use language reflecting movements, vocalisations and actions can help create connections, you are confirming the person’s presence and actions in the world and treating them as an equal.

- Communication can be tiring when you have to rely on reduced hearing and vision, use touch or other ways to communicate. Make sure you build in plenty of time for breaks. Interpreters and 1:1 support roles will also need regular breaks.

Moving around and independence

- Try to keep things in the same place in a room – this helps the person to map their environment. Don’t leave things on the floor or in the middle of the room as it creates a trip hazard and may restrict independent movement.

- Use colour contrasts or tactile markers in the environment. High contrasts around doorways, between floor and walls, furniture and other items in the room help the person to locate and orientate. Tactile markers can be used to show particular details – things like ‘bump ons’ can be used to indicate positions on dials (oven, thermostat or washing machine). Simple strategies like using a number of rubber bands on canned food can help to differentiate between items.

- There is an increasing role for assistive technology to increase independence around the home. Alexa, Siri and Google services have been helpful to provide information and access control of the environment.

- If the person needs assistance with guiding, ask them about their preferred way to be guided. Usually a guide will walk a step in front with the person holding onto the guide’s elbow, some people prefer to link arms or hold the forearm. Try to walk at a comfortable pace for both of you. Never grab, push or drag a person when guiding them.

- When passing through a door the guide will usually open the door with their free hand and drop their guiding arm behind them. This signals to the person that they need to follow you single file through a narrower space.

- When guiding someone to a chair, stop in front of the chair and let them know a seat is available, they should offer you their hand. Place the person’s hand on the back of the chair so that they can orientate themself and take a seat.

- If you need more information about guiding strategies you are advised to seek training from local vision impairment support service. The RNIB provides general advice about guiding a blind or partially sighted person.

(Deafblind UK, 2020; Hicks, 1999; Sense, 2019)

Public health and deafblindness

Public health in relation to deafblindness:

- Deafblind people are considered a hidden group – a ‘low incidence, high needs’ group (Gray, 2006).

- Access to appropriate early intervention relies upon appropriate identification and the recognition of deafblindness as a unique disability (Murdoch, 2002).

- Some groups of people may be at higher risk of deafblindness due to their sensory impairment, or genetics (Dammeyer, 2013; Kancherla et al, 2013). People with deafblindness may be at higher risk of mental health issues, these include social exclusion, anxiety and depression (Bodsworth et al, 2011; Högner, 2015; Wahlqvist et al, 2016).

- People with deafblindness experience difficulties and inequalities accessing education, healthcare, employment and social life (Jarrold, 2014; World Federation of the Deafblind, 2018).

- Deafblindness can occur as a consequence of low uptake of vaccination (eg MMR); deafblindness as a consequence of Rubella syndrome has been eliminated in parts of the world with high uptake rates (WHO, 2018).

- People with deafblindness need multidisciplinary management and support. Within the multidisciplinary team, SLTs have an important role in differential diagnosis (in the prevention of diagnostic overshadowing) as well as management and training in relation to methods of communication and co-occurring eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties.

Further information:

- Mapping opportunities for deafblind people across Europe (PDF)

- At risk of exclusion from CRPD and SDGS Implementation: Inequality and persons with deafblindness. Initial Global Report 2018

- Campaign to End Loneliness

For more information see the RCSLT’s information on public health.

Resources

RCSLT

National organisations

- Deafblind UK

- NatSIP – The National Sensory Impairment Partnership

- Scottish Sensory Centre

- Sense – for people with complex disabilities and deafblindness

Family and patient support groups

- Alstrom Syndrome UK

- Bardet Beidl UK

- Contact

- CHARGE Family Support Group

- CMV Action (Cytomegalovirus)

- Down’s Syndrome Association

- FASD Network UK (Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder)

- Headway (The Brain Injury Association)

- Meningitis Now

- The Norrie Disease Foundation

- Usher Kids UK

- Wolfram Syndrome UK

- Zellweger Family Support Group UK

International organisations

- Deafblind International

- Nordic Welfare Centre

- Perkins International and Perkins School for the Blind

If you would like to speak to an adviser in this area, please contact us.

Related topics

Types of hearing and vision problems

To learn more about specific types of hearing or vision problems, see our clinical information on:

Sensory integration

Some people who are deafblind can experience challenges in understanding and incorporating their senses which can result in daily challenges for them and those around them. This is more than just the difficulties with the individual senses, but is about integrating and understanding the senses together.

“Sensory integration is the ability to assimilate sensory information from the body and environment for use” (Ayres 1979, 2005)

The research in this area regarding sensory integration therapy is limited. There is value for people who are deafblind is considering practical sensory integration strategies and evaluating them on an individual basis.

When assessing and considering sensory integration strategies it is advisable to involve practitioners with appropriate experience and advanced skills in this area.

Deafblindness and autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

ASD presents with a number of characteristics that are also present in individuals with deafblindness. There is a higher incidence of neurological disorders in the sensory impairment population and therefore a dual-diagnosis shouldn’t be disregarded (Kancherla et al, 2013).

When considering a diagnosis, assessment teams will need to think about the difference between the impact of sensory impairment and differences shown in ASD. Table 1 shows how the sensory impairment affects development and how they can be interpreted through an ASD diagnostic lens.

Table 1: A comparison of how sensory impairment impacts on development and how these may be viewed in the context of ASD (based on the work of Matthew and Rose, 2013).

Deafblindness can result in: |

Which can be interpreted in the context of ASD as: |

| Difficulties regulating and modulating sensory information | Repetitive sensory behaviours, restricted interests |

| Lack of recognition by others on attempts to communicate and missed responses to overtures of others | Reduced social communication |

| Idiosyncratic communication style | Communication difficulties |

| Differences in joint attention | Lack of joint attention |

| Desire to create predictability to make sense of the world | Repetitive behaviours/rigidity/difficulties with change |

| Frustration and misunderstanding about the world | ‘Meltdowns’ |

| Limited access to peers or opportunities to make friends, and a dependence on others to mediate interactions | Social interaction difficulties |

Assessment and diagnostic teams considering ASD in the context of deafblindness should involve practitioners with appropriate experience and skills in both impact of sensory impairment and development in people with deafblindness, and understanding of sensory issues and diagnosis of ASD.

For more information about supporting people with ASD, see our clinical information on autism.

Deafblindness and profound and multiple learning disability (PMLD)

People with profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD) have more than one disability, where the most significant is a profound learning disability.

Many, but not all, people who have PMLD may have a form of functional deafblindness in that they may not understand the auditory, visual and other sensory information they receive.

However, if there is a difference between expected sensory response and overall developmental and cognitive ability, deafblindness may multiply the difficulties the person has.

It is advisable to involve practitioners with appropriate experience and skills in both PMLD and sensory impairment when evaluating the impact of deafblindness in the context of PMLD.

To learn more about supporting people with profound and multiple learning disabilities see our learning disabilities clinical information.

Further guidance

Deafblind people may benefit from many disciplines within speech and language therapy practice.

These topics may be of particular interest:

- Augmentative and alternative communication

- Autism

- Bilingualism

- Brain injury

- Cleft lip and palate

- Craniofacial conditions

- Deafness

- Dementia

- Dysphagia / eating, drinking and swallowing difficulties

- Learning disabilities

- Mental health (adults)

- Neonatal care

- Progressive neurological disorders

- Social emotional mental health

- Stroke

- Visual impairment

Contributors

Authors

- Steve Rose

- Grainne Livingstone

- Beccy Timbers

- Heather Trott

Acknowledgements

- Members of the MSVI CEN

- Julia Hampson

- Seeta Shah

- Gwyneth Terell

With thanks to the people with deafblindness, family members and colleagues who took the time to comment on member and public guidance and inform the authors’ understanding and perspective.

References

Alsop, L., Berg, C., Hartman, V., Knapp, M., Lauger, K., Levasseur, C., Prouty, M., and Prouty, S. (2012) A Family’s Guide to Interveners. SKI-HI institute.

Bodsworth, S. M., Clare, I. C. H., Simblett, S. K., and Deafblind UK (2011) Deafblindness and mental health: Psychological distress and unmet need among adults with dual sensory impairment. British Journal of Visual Impairment. 29(1), 6–26.

British Deaf Association (2018) Help and Resources for British Sign Language.

Costain Schou, K., Gullvik, T., and Forsgren, G. A. G. C. (2017) The importance of the bodily-tactile modality for students with congenital deafblindness who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Dbi Review.

Dammeyer, J. (2013) Symptoms of Autism among children with congenital deafblindness. Journal Autism and Developmental Disorders. 44(5).

Deafblind UK (2020) Living better with sight and hearing loss.

Goldbart, J., and Caton, S. (2010) Communication and people with the most complex needs: What works and why this is essential. Research Institute for Health and Social Change Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) and Mencap.

Gray, P. (2006) National audit of support, services and provision for children with low incidence needs (Research Report No 729). DfES Publications.

Hendrickson, H., and McLinden, M. (1996) Using Tactile Symbols: A review of current issues. Eye Contact.

Hicks, G. (1999) Making Contact Sense UK

Högner, N. (2015) Psychological Stress in People with Dual Sensory Impairment through Usher Syndrome Type II. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness. 109(3), 185–197.

Jarrold, K. (2014) European Deafblind Indicators – Mapping Opportunities for Deafblind People Across Europe. European Deafblind Network.

Kancherla, V., Van Naarden Braun, K., and Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2013) Childhood vision impairment, hearing loss and co-occurring autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Health Journal. 6(4), 333–342.

Mathy-Laikko, P., Iacono, T., Ratcliff, A., Villarruel, F., Yoder, D., and Vanderheiden, G. (1989) Teaching a child with multiple disabilities to use a tactile augmentative communication device. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 5, 249–256.

Matthew, G., and Rose, S. M. (2013, August 23) Differences and similarities between Autism and Deafblindness – Exploring Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the often reported “autistic traits” in people who are Deafblind or Multi-Sensory Impaired (MSI). 8th Deafblind International European Conference, Lille, France.

McLarty, M. (1997) Putting objects of reference in context. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 12(1), 12–20.

Murdoch, H. (2002) Early intervention for children who are deafblind (p 24). Sense.

Nafstad, A. V., and Rødbroe, I. B. (2013) Communicative Relations: Interventions that create communication with persons with congenital deafblindness (English Edition). Stadped Sørøt, Fagavdeling døvblindhet/kombinerte syns-og hørselsvansker.

NatSIP (2019) Accessing Sign Language in the Tactile Modality V.2. NatSIP/DfE.

Ockleford, A. (2002) Objects of reference (3rd edition). RNIB.

Palmer, R. (2018) Social-Haptic Communication. Russ Palmer, International Music Therapist.

Reed, C. M. (1996) The implications of the Tadoma method of speechreading for spoken language processing. Proceeding of Fourth International Conference on Spoken Language Processing. ICSLP 1996, 3, 1489–1492.

Robertson, J., and Emerson, E. (2010) Estimating the number of people with co-occurring vision and hearing impairments in the UK – Research Portal | Lancaster University. Centre for Disability Research.

Rowland, C., and Schweigert, P. (2000) Tangible Symbol SystemsTM Making the right to communicate a reality for individuals with severe disabilities (2nd edition). Oregon Institute on Disability and Development: Design to LEARN Projects.

Schweigert, P. (1989) Use of microswitch technology to facilitate social contingency awareness as a basis for early communication skills. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 5, 192–198.

Schweigert, P., and Rowland, C. (1992) Early communication and microtechnology: Instructional sequence and case studies of children with severe multiple. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 8, 273–286.

Sense (2019) Tips for meaningful communication.

Sigafoos, J., Didden, R., Schlosser, R., Green, V. A., O’Reilly, M. F., and Lancioni, G. E. (2008) A Review of Intervention Studies on Teaching AAC to Individuals who are Deaf and Blind. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 20(1), 71–99.

Wahlqvist, M., Möller, C., Möller, K., and Danermark, B. (2016) Implications of Deafblindness: The Physical and Mental Health and Social Trust of Persons with Usher Syndrome Type 3. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness. 110(4), 245–256.

WHO. (2018) Vaccine Preventable Diseases Surveillance Standards Congenital Rubella Syndrome. World Health Organisation.

World Federation of the Deafblind. (2018) At risk of exclusion from CRPD and SDGs implementation: Inequality and Persons with Deafblindness. World Federation of the Deafblind.