This guidance was co-produced by autistic people, parents of autistic children and adults, and both autistic and non-autistic SLTs.

(Last updated October 2023)

About

Speech and language therapists (SLTs) should approach this guidance with an awareness that knowledge of autism continues to evolve within the fast-changing field of neurodiversity and with a diversity of views. Throughout, we reiterate the need for evidence-based practice (EBP). SLTs are encouraged to think sensitively and reflectively, base clinical decisions around the needs and preferences of each individual child or adult and approach all sources of information with an open and critical mind, being aware that there may be newer information and perspectives to consider.

This guidance was co-produced by autistic people, parents of autistic children and adults, and both autistic and non-autistic SLTs. For further details, see the contributors’ section.

This guidance aims to:

- Support RCSLT members to recognise, assess, and offer intervention and support to autistic people (see Definitions and Terminology section) and their support networks, using EBP and meeting statutory requirements. This includes identifying and understanding related co-occurring diagnoses and considering any other possible reasons why needs and intersecting identities may present differently across different settings.

- Encourage RCSLT members to place the lived experiences of all autistic people and their families at the centre of practice, to advocate for reasonable adjustments and to recognise, avoid, counter and challenge discrimination. Decisions on approaches to intervention and support will be in the best interest of the autistic person based on a well-informed choice and mutually considered by all involved stakeholders.

- Provide clarity and scope about the role of the SLT working with autistic people and support networks. This will include current and potential roles to advise RCSLT members, families, other professional groups, commissioners and policy makers.

Definitions and Terminology

Throughout this guidance we use the term ‘autism’ to represent variations in the diagnostic terms used. We acknowledge that existing diagnostic manuals use ‘autism spectrum disorder – ASD’, others prefer ‘autism spectrum condition – ASC’.

We use identity-first language i.e. ‘autistic person’ as it is currently considered to be the most preferred term; others prefer ‘person with autism’ (see Bury, S.M., Jellett, R., Spoor, J.R. and Hedley, D., 2023). We respect and encourage prioritising individual preference (Kenny et al 2016; Botha et al 2021). When quoting from original sources we retain the language of the original article. We have aimed to include co-produced research; however, we are aware that many of the included references and resources are not, and do not, use neurodiversity affirming language.

This guidance takes a lifespan approach. We will use words such as people or individuals when referring to all ages, only specifying child/young person or adult when a statement refers specifically to that age group. We have acknowledged the range of presentations and co-occurring diagnoses in our recommendations. This means, for example, that some recommendations relate to autistic people and others for autistic people with a learning disability.

See the glossary for definitions of specific terms.

Setting the scene in autism: neurodiversity and the neurodiversity movement

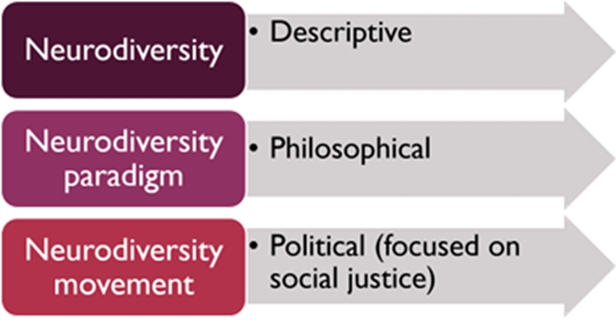

In this section, we provide a brief summary of neurodiversity, introducing descriptive, philosophical and political terminology. Within neurodiversity, there is a diversity of perspectives and sensibilities. This guidance is focused on autism, whereas neurodiversity is broad and neurodivergences can be multiple. For further information on other neurodivergences, you may wish to explore other sources of information. This area continues to evolve and we encourage SLT to ensure their knowledge is up to date through checking sources and evaluating information critically.

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity refers to the natural variation in human neurological development across society. It refers to the diversity of brains and minds and the way we experience and interact with the world or that there are different ‘neurotypes’. While many follow the neurodevelopmental pathway of the majority i.e. neurotypical, others have neurodevelopment that diverges from this and may identify as neurodivergent. The term ‘neurodivergent’ was introduced by Kassiane Asasumasu in 2000 (Walker & Raymaker 2021) to simply refer to a brain that diverges from typical.

The neurodiversity paradigm

The neurodiversity paradigm (Walker 2014) states that in naturally occurring neurodiversity, one way of being is not better than another. There are different neurotypes just as there are different characteristics such as ethnicity or gender; and equally, that there is no ‘right’ characteristic or neurotype. Neurodiversity is affected by the same social dynamics as other characteristics such as inequalities of social power, unconscious bias and prejudice. The neurodiversity paradigm values the strength and creative potential of diversity.

The neurodiversity movement

The neurodiversity movement is a political movement and in the context of a heterogenous population, a diversity of views exists and there is not universal agreement with some of its ideas. It is important that all ideas are open to critical scrutiny, debate and discussion in order to progress towards a future with better understanding of all perspectives.

For a fuller perspective in autism, see:

- Kapp, S.K., 2020. Autistic community and the neurodiversity movement: Stories from the frontline (p. 330). Springer Nature.

- Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K.L., Ellis, C. and Dekker, M., 2021. Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology (p.782).

The neurodiversity movement developed from the Autism Rights Movement in the 1990s, who embraced the term neurodiversity, attributed to sociologist Judy Singer (Singer 1999). Neurodiversity has always referred to all people. It includes neurotypical people as well as those with neurological and developmental differences including autism and, for example, those with attention and hyperactivity differences or language or learning differences.

To promote the recognition of a minority group status for individuals who differ from the majority such as autistic people, Nick Walker introduced the term ‘neurominority’ (Walker 2014; Walker & Raymaker 2021), with the rest of the population referred to as the ‘neuromajority’. This movement is aligned with disability and human rights and is focused on social justice. It aims for the acceptance and inclusion of all people, eradicating stigma, and promoting equality for neurological minorities. Their overarching goal is a neurodiversity-affirming social model of disability.

For autistic people, in addition to existing human rights and equality and diversity legislation, the Neurodiversity Movement asks that:

- autistic and neurotypical stakeholders work together across health, education, social care and research to support this social justice movement.

- quality of life, including adaptive functioning (e.g. self-determination and rights, well-being, social relationships and inclusion, and personal development) is at the centre (Knapp 2020).

- support and interventions are strength-based (focused on improving subjective quality of life and wellbeing), with the assent or consent of the autistic person, acknowledging that a minority may require a Best Interest decision. See RCSLT Shared decision making and mental capacity guidance.

- autistic ways of being are accepted and preserved.

- autistic people are supported to follow their own developmental trajectory.

- competence is presumed (until proven otherwise).

- the Double Empathy Problem (Milton 2012) is considered:

“.. It is the idea that rather than viewing autistic social differences as inherent deficits, that we instead recognize that perhaps non-autistic miscommunication has just as much role in autistic social difficulties as autistic people themselves do. That non-autism is just as baffling to autistic people as autism is to non-autistic people..” The Double Empathy Problem – A Paradigm Shift in Thinking About Autism – Speaking of Autism….

The neurodiversity movement, aligned with the social model of disability, emphasises societal and environmental barriers as contributors to disability. Autism is seen to be a neurological difference with any disability arising as a result of living in a society designed largely for the neuromajority. Historically, the medical model, with its focus on deficits or impairments, has driven autism research (see Pellicano and Den Houting 2021) and the development of interventions. This has contributed to a focus on teaching autistic people skills so that they behave like the majority and appear ’normal’. The neurodiversity movement does not oppose the medical model, valuing its importance in providing treatments for co-occurring mental and physical health needs. Their criticisms of particular treatments and intervention approaches are grounded in the belief that aiming to normalise someone’s behaviour is a form of ableism (i.e. discrimination, bias and prejudice against the disabled), inferring inferiority and favouring the non-disabled.

As the neuromajority are also neurodiverse, the negative connotations associated with the concept of behaving ‘normally’ is universally unhelpful. Supporters of the neurodiversity movement consider that such teaching risks causing an individual to mask their difficulties, which in turn can affect mental wellbeing (e.g. Cage & Troxell-Whitman 2019), and in some cases, results in trauma (see e.g. Kerns, Newschaffer, and Berkowitz, 2015; Hoover 2015; Rumball, Happé, and Grey, 2020).

“While the movement disagrees with certain principles, means, and goals of interventions, with those caveats, it does support therapies to help build useful skills such as language and flexibility. It opposes framing these matters in unnecessarily medical or clinical ways;” (p.8 Knapp 2020)

Other models of disability have been summarised below to aid understanding of our previous explanations.

- Social model of disability: The social model centres the structure of society (social, cultural, political and environmental) as the main contributor to a person’s experience of disability as opposed to the individual’s differences from the majority. It focuses on removing societal barriers to inclusion and participation.

- Medical model of disability: This model places the individual’s ‘symptoms’ at the centre and that it is these ‘impairments’ that are directly disabling them and excluding them from society. This model, originating in physical disease, is focused on treating or curing impairments.

- The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning (ICF), based on the Biopsychosocial Model, has been proposed as one way or bridging the gap between the medical and social model (Bölte et al 2021; Bölte 2023). For further information see ICF Core Sets for ADHD and autism – Karolinska Institutet

- Biopsychosocial Model (Engel 1977): The biopsychosocial approach systematically considers biological, psychological, and social factors and their complex interactions in understanding health, illness, and health care delivery. It suggests that how well a person manages in life is a complex interaction between all three factors. Assessment should identify which aspects of the three domains are the most important to promoting and supporting a person’s health and wellbeing.

- Other proposed models of disability include: The Affirmative Model of Disability (see Swain, J. and French, S., 2000. Towards an affirmation model of disability. Disability & society, 15(4), pp.569-582.)

Setting the scene in autism: RCSLT Neurodiversity statement

The RCSLT values that we live in a society that is enriched by diversity, including neurodiversity. We recognise that differences exist between individuals, rather than deficits, and recognise disability. The RCSLT encourages members to acknowledge and appreciate individual needs, the impact of these, and to value the rights and autonomy of all people.

In a society largely designed for the neuromajority, we commit to taking deliberate steps to develop neurodiversity affirming practice within our profession. We commit to understanding the needs and preferences of neurominorities such as autistic people, including listening to parents and carers of people who cannot make these decisions themselves. This includes the ways in which autistic individuals are excluded or included, the ways we can make adjustments to everyday expectations, interactions and environments, and the teaching and sharing of specific skills where this supports quality of life, inclusion and reduces risk and harm. In particular, our profession has a key role in optimising communication experiences via the use of a neurodiversity informed lens.

Setting the scene in autism: Terminology

Words matter

In addition to our use of ‘autism’ and identity first language, we present other important terms for consideration, acknowledging that language continues to evolve. As speech and language therapists (SLTs), we recognise that words matter and the language we use has an effect. We sometimes work within the confines of a medical model where there is a disconnect between the clinical diagnostic language of professional reports and the positively-framed, individually affirming language of formulation and intervention/support, even when needs and disability are clearly described.

We recognise the balance required in using the language of difference versus deficit in a society where resources are limited and access is restricted to those showing a ‘clinically significant impairment’ (see Jellett and Muggleton; 2022) and often with a request for a qualifier such as ‘severe’. We encourage SLTs to advocate for a neurodiversity-affirming approach in all areas of practice, including the multi-disciplinary team and with system leaders. We also acknowledge that at present the use of positive and inclusive language without reference to difficulties and challenges, could risk preventing access to services, obtaining a diagnosis and receiving support. In addition, this may indirectly invalidate reports from the individual and their family.

SLTs should base their selection of language style (deficit-based or positively framed and individually affirming) on the needs of the autistic person at that time and knowledge of local services’ access requirements. This should be clearly explained, discussed and agreed with the autistic person and/or their parents/carers, particularly where an autistic person lacks the specific mental capacity to make this decision. Subject to the resources of individual services, consideration could be given to producing two versions of a written document containing the same information using both language styles depending on the aim of the report i.e. accessing support or affirming a person. Two examples of neuroaffirmative style reports one for adults and one for children are provided in our resources (see also Role of SLT: Transitions – Sharing Information)

What does neurodiversity informed in the context of autism mean?

- Putting co-production at the heart of service delivery across health, education, social care and in research.

- Drawing on the knowledge of those with lived experience, being cognisant of autistic voices and neurodivergent led or co-produced resources and the experiences of parents/carers of individuals unable to make decisions for themselves.

- Recognising and valuing that being autistic or neurodivergent is a valid lived-identity – not a set of symptoms to be treated.

- Recognising sources of disability and having a difference not deficit and environment first mindset i.e. change the context not the person.

- Using strength-based approaches to developmental differences that focus on harnessing a person’s strengths, interests and abilities and aim to provide support and adaptations that affirm an individual’s neurodivergent identity, if this makes sense to the individual concerned. E.g. Autistica Action Briefing: Strengths-based Approaches.

How to use terminology

With a commitment to being neurodiversity affirming and with the caveat above, consider:

- asking the autistic individual (or their parent/carer/advocate when a person does not have the capacity to make a decision) about their preferences relating to language and terminology; e.g. ‘autistic person’ or ‘person with autism’. For further reading see Vivanti 2020 and Botha, Hanlon & Williams 2021.

- avoiding the use of functioning labels such as high or low functioning or severity indicators such as mild, moderate, severe in relation to autism. These risk ableism and stigma and can minimise or dismiss the needs of those described as high functioning. Think about ways to describe the level of an autistic person’s support needs during a particular time or place. You should also acknowledge that these may change over time and context. There will be times when it’s appropriate to use clinical language over affirming language. Everyone presents differently across settings and time and such qualifiers are likely subjective and variable.

- the audience and needs of the individual autistic person. Parents of newly diagnosed children may request these labels to increase their understanding of their child’s future. We encourage honest and open conversations with families more broadly regarding what can be known about their child’s developmental trajectory. We note that there is a non-mandatory recommendation by an international consortium of academics and people with lived experience, to use the term ‘profound autism’ as an opportunity to ensure those who are disabled with the highest support needs are recognised, highlighting their needs to ensure the development of and access to services across the world, including third world countries (Lord et al 2022). We recognise that there is continued debate regarding the use of this term. For comments and responses, see the resources section. We also acknowledge that various systems e.g. education, may use functioning descriptors to contribute to the allocation of funding bands.

- using the word difference instead of deficit or impairment, where appropriate and if preferred by the individual. Ensure needs, level of impact and disability are well defined.

- using the term co-occurring instead of co-morbid for additional diagnoses.

- referring to distress, decisions, actions and responses instead of challenging behaviour or behaviour that challenges. This approach focuses on the individual and their engagement rather than the difficulties these outcomes present for the people around them. We acknowledge that use of these terms remains common with families, and in other sectors and professions, which may require use of all terms initially to ensure there are no barriers to communication.

- taking an active role in advocating for the appropriate use of neuroaffirmative language for example when working in a multi-disciplinary context.

Setting the scene in autism: Overview

What is autism?

Autism is a disability affecting neurodevelopment and characterised by differences in:

- social interaction

- speech, language and communication

- learning, thinking and processing

- experiencing feelings

- intensity of interests and sensory processing.

It is highly heritable, with many genes contributing. Co-occurring diagnoses are common, including learning disability, and it persists across the lifespan. It is usually associated with average intellect where it is considered part of the range of natural variation in neurodiversity, bringing both challenges requiring support and strengths (adapted from Mandy 2019). As many as 50% of autistic people have high support needs that continue throughout life (Lord et al 2022).

Some autistic people do not identify as disabled.

How common is autism?

Current global estimates vary but are increasing, with the median estimates of prevalence (the frequency of autism in a population at any one time) ranging from 0.6 – 1 in 100 being autistic (Salari et al 2022; Zeidan et al 2022). Across the world, the reported ratio of males to females is now considered to be 4:2 (ratio as specified in Zeidan et al 2022) and the proportion of those diagnosed with a co-occurring learning disability is estimated at 33% (Zeidan et al 2022). For children with a learning disability in the US, the proportion of those with the highest support needs is approximately 28%. These children require around the clock supervision, are non-speaking and often with epilepsy and self-injury (Hughes et al; 2023).

Within the UK estimates vary. In Scotland a population study using the 2011 Census indicated that 1.6% of the population had autism, and that of those, 20% had an additional learning disability (Kinnear et al 2020). This rate varied, seemingly dependent on which diagnosis was recorded first and whether it refers to a child or adult:

“Of the children and young people with intellectual disabilities, 3,756/9,396 (40.0%) additionally had autism, and of the adults aged 25 years and over with intellectual disabilities, 1,953/16,953 (11.5%) additionally had autism. Of the children and young people with autism, 3,756/25,063 (15.0%) additionally had intellectual disabilities, and of the adults aged 25 years and over with autism, 1,953/6,649 (29.4%) additionally had intellectual disabilities.” (p. 1063 Kinnear et al 2020)

In Northern Ireland, published statistics for school-aged children only (aged 4-15 at the start of the school year) indicates a prevalence rate of 5% within the school-aged population (see The Prevalence of Autism (including Asperger Syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland Annual Report 2023.

Trends in diagnosis are also changing, for example in the UK between 1998 and 2018, a 787% rise in incidence (newly diagnosed) was identified, with greater increases in adults, females and those without learning disability (Russell et al 2022; in Wales: Underwood et al 2022).

NOTE: The statistics above are only estimates at a single point in time and with limitations due to for example, research methodologies, variability in estimates, evolving trends in who are receiving diagnoses, the likelihood of under diagnosis in certain ethnic groups (e.g. de Leeuw, Happé & Hoekstra 2020) and lack of acknowledgement of gender diversity.

Diagnostic criteria

To assist in the diagnosis of autism in the UK, professionals involved in the diagnostic assessment, including speech and language therapists (SLTs), use one of two references. These references aim to provide standardised criteria to inform diagnostic decision making.

- The International Classification of Diseases 11th edition (ICD-11) provides the following summary: “Autism spectrum disorder is characterised by persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and to sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication, and by a range of restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests or activities that are clearly atypical or excessive for the individual’s age and sociocultural context. The onset of the disorder occurs during the developmental period, typically in early childhood, but symptoms may not become fully manifest until later, when social demands exceed limited capacities. Deficits are sufficiently severe to cause impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and are usually a pervasive feature of the individual’s functioning observable in all settings, although they may vary according to social, educational, or other context. Individuals along the spectrum exhibit a full range of intellectual functioning and language abilities.” ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (who.int)

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, 5th Edition, Text revision (DSM-5-TR) (US based) provides the following description (NB specifications of the number of symptoms are required and examples of symptoms are provided but not included here). The DSM-5-TR requires that co-occurring diagnoses and severity are specified and it defines “severity levels” according to the degree of support required 1: requiring support; 2: requiring substantial support; 3: requiring very substantial support.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, for further details https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html

A. “Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, currently or by history.

B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, currently or by history.

C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.”

How does autism present?

“When you know one person with autism, you know one person with autism.” (Dr Stephen Shore)

Autism across cultures

Interaction styles and social expectations are embedded in culture and society. Although many similarities exist across cultures, so do differences. To date, the majority of autism research from which much of our understanding has developed, is skewed towards high-income western countries and within this body, ethnic minorities are underrepresented (de Leeuw, Happé & Hoekstra 2020). As a result, it is likely that our knowledge of how autism presents, how we recognise, assess and diagnose, and how we provide interventions and support autistic people, risks being culturally biased.

It is known that the broad areas of difference in autism are the same across different ethnic groups around the world but that the specific features or examples can differ qualitatively, quantitatively and in their impact on daily living for the autistic individual (de Leeuw et al 2020).

Autism across age groups

Just like everyone, autistic people have their own individuality, personality and strengths which can change and develop across the life-course influenced by their experiences through life, society and the wider environment. It can be helpful, particularly in recognising autism pre-diagnosis, to consider what autistic features are most relevant across different age groups. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical guideline [CG128]: Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis, has a helpful summary table for children. The NICE clinical guideline [CG142] for adults, provides a list of possible features to consider in Recommendations section 1.2.

Autism and individuals’ assigned female at birth (AFAB)

In the past, there has been an underrecognition of autism in individuals AFAB and concerns about misdiagnosis in this group. This led to the identification of a different presentation of autism, now acknowledged as non-gender exclusive. Assigned Male at Birth (AMAB) individuals may present with the type of presentation described here and equally AFAB individuals may present with more traditional descriptions of autism that were previously thought to be more associated with AMAB individuals. These may (or may not) be in the absence of gender identity differences. For further learning on the intersection of autism and gender identify and dysphoria – see Adapting health services to meet the needs of autistic people with gender dysphoria (Strang et al 2018; Cooper, Mandy, Butler & Russell et al 2022, Cooper, Butler, Russell & Mandy 2022).

Recognition of this presentation remains important for all individuals and is thought to refer to masked autism (see Pearson & Rose 2021). A summary of this different behavioural expression of autism is provided below; for further reading see for example: Bargiela et al 2016; Howe et al 2015; Zener 2019). The cited research refers to girls and women and boys and men, although not inclusive, these terms have been retained for this summary. Hull and colleagues (2020) proposed the following key differences in core features of autism.

Autistic girls/women:

- are thought to have greater interest and intent in forming social relationships but may struggle to maintain such relationships and find conflict within them harder to manage.

- may either have fewer repetitive behaviours or intense interests or that these interests are in different areas to boys/men, and/or are in areas that are typical in non-autistic but with greater intensity. The perceived acceptability of the type of interest may mean that it causes fewer overt social problems but nevertheless it risks this feature being overlooked by parents/carers and professionals.

Other relevant differences

Autistic girls/women:

- are thought to internalise emotional difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, self-harm and eating problems, to a greater degree than autistic boys and men. When severe, these difficulties may mask autism symptoms and a co-occurring mental health problem diagnosed but not autism. Internalising difficulties rather than externalising them (more common in autistic boys and men), such as through aggression, may also contribute to the gender bias in recognition as their needs are further hidden.

- may be more likely to camouflage, mask or compensate for their differences. This refers to the conscious or unconscious use of techniques to hide differences when in a social context, often driven by anxiety in response to the attitudes and responses of others. The techniques can be developed implicitly or explicitly learned. Whilst this may have advantages in a specific situation, the cost over time to mental wellbeing can be significant and (Chapman et al 2022).

*for further reading about these well-established phenomena, see our resources section.

Self-identification

Increasingly, some adults and young people self-identify as autistic often in the wake of typically extensive research, driven by a desire to seek a greater understanding of themselves e.g. What it’s Like Being a Self-Diagnosed #ActuallyAutistic Adult – The Art of Autism (Uselton 2020). For some this has happened while waiting for formal assessment. For others, it follows their child’s diagnosis of autism as they explore the literature to enhance their understanding of their autistic child. A proportion go on to seek formal diagnosis but many do not due to barriers to diagnosis as an adult that include the limited availability of diagnostic services, long waits and professionals’ perceptions (Lewis 2017; Crane et al 2018). This is despite access to diagnosis being a right with all localities expected to have a diagnostic pathway (Autism Act 2009).

Some people find that knowing and seeing themselves as neurodivergent and not ‘wrong’ is enough and find seeking formal diagnosis unnecessary. This can be the case whether they would be considered as meeting the criteria or not. Self-identification is not without controversy, and can risk misdiagnosis, especially as clinical diagnosis is reached via consensus rather than the viewpoint of a single person. It also risks a person’s needs being under recognised. For example, not identifying co-occurring problems and missing the opportunity to receive support and access Government benefits (Self-Diagnosed Autism: A Valid Diagnosis? – Autism Parenting Magazine (Loftus 2022)).

SLTs should support adults to access diagnostic assessment. This can include signposting to relevant services and support groups.

Co-occurring diagnoses and differential diagnosis

The frequency of co-occurring disabilities with autism is high (e.g. Levy et al. 2010). Autism guidance from all four UK nations recommends identifying any additional co-occurring diagnoses including recognising an individual’s strengths and needs. Understanding a person’s profile in this way is essential in identifying intervention and support needs as well as considering the impact of additional differences, the identification of any recommended treatment for co-occurring diagnoses and reducing the risk of missed or delayed diagnosis. As people change across their lifespan, so may their profile and the addition of new diagnoses or changes to diagnosis may be required. For example, an anxiety diagnosis (or any other mental health problem) can be given independently of autism or anxiety may occur because autism could not initially be recognised.

A number of other neurodevelopmental diagnoses may co-occur with autism and can be difficult to distinguish from each other, particularly in early stages of development. These are:

- learning disability (also referred to in the literature as intellectual disability/intellectual developmental disorder)

- language disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- tic disorders and developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD), which collectively are sometimes referred to as ESSENCE (Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations) (Gillberg 2010).

Other diagnoses also co-occur or may be an alternative explanation (a differential diagnosis) of an individual’s neurodivergence. Examples are included below – the first is relevant for children and young people, and the second for adults, noting overlaps and differences; both from the NICE autism guidelines.

Recommendations – Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis (NICE CG128) (NB specific language disorder is now known as Developmental Language Disorder, with language delays referred to as speech language communication needs.)

“1.5.7 Consider the following differential diagnoses for autism and whether specific assessments are needed to help interpret the autism history and observations:

- Neurodevelopmental disorders:

- specific language delay or disorder

- a learning (intellectual) disability or global developmental delay

- developmental coordination disorder (DCD).

- Mental and behavioural disorders:

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- mood disorder

- anxiety disorder

- attachment disorders

- oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

- conduct disorder

- obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Conditions in which there is developmental regression:

- Rett syndrome

- epileptic encephalopathy.

- Other conditions:

- severe hearing impairment

- severe visual impairment

- maltreatment

- selective mutism.”

Recommendations – Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (NICE CG142)

“1.2.10 During a comprehensive assessment, take into account and assess for possible differential diagnoses and coexisting disorders or conditions, such as:

- other neurodevelopmental conditions (use formal assessment tools for learning disabilities)

- mental disorders (for example, schizophrenia, depression or other mood disorders, and anxiety disorders, in particular, social anxiety disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder)

- neurological disorders (for example, epilepsy)

- physical disorders

- communication difficulties (for example, speech and language problems, and selective mutism)

- hyper- and/or hypo-sensory sensitivities.”

These lists are not exhaustive and reflect the complexity of understanding an individual’s neurodevelopmental profile of strengths and needs. Below, we provide further examples. Though not a wholly evidence-based list, but drawing attention to other specific diagnoses or differences considered important by those with lived experience of autism and others. Being autistic does not preclude a person from having any other physical or mental health problem:

Other mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental diagnoses or differences (listed alphabetically not by magnitude or prevalence in autism):

- childhood apraxia of speech/verbal dyspraxia

- dissociative disorders (including Dissociative Identity Disorder – DID)

- eating disorders (see PEACE and Babb et al 2021): including pica and Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) (see e.g. Farag et al 2021; Bryant-Waugh, R., Loomes, R., Munuve, A. and Rhind, C., 2021)

- foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) (see Home – National FASD)

- Fragile X

- functional neurological disorder

- gender dysphoria (see for example Strang et al 2018; Cooper, Mandy, Butler & Russell et al 2022, Cooper, Butler, Russell & Mandy 2022)

- personality disorders

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (C-PTSD)

- trauma: autistic individuals can experience Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs) and traumatic experiences both separate and related to their autism (see e.g. Kerns, Newschaffer, and Berkowitz, 2015; Hoover 2015; Rumball, Happé, and Grey, 2020)

- specific Learning difficulties e.g. Dyslexia, dyscalculia

- stammering/stuttering/dysfluency

Other physical health conditions:

- Ehlers-Danlos syndromes

- fibromyalgia

- gut problems

- hypermobility

Other differences:

- Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) – this is a much-debated term however the experience of demand avoidance or anxiety is one recognised by many (for discussion see O’Nions et al. 2017; Malik & Baird 2018; Green et al. 2018; Woods 2019).

Neurodevelopmental pathways to diagnosis

Traditionally, diagnostic pathways and guidance are centred around specific diagnoses, having separate pathways for autism, for ADHD and for mental health. Grey areas can exist as to how other needs are diagnosed, for example with learning disability, which tends not to have a well-defined pathway (calls for a NICE guideline on Learning Disability in children and young people have been made). Approaches to assessment that consider any possible neurodevelopmental diagnosis do exist but are typically in tertiary services. Diagnosis-specific pathways can make it challenging to fully understand a neurodivergent person’s profile and identify their support needs. It can mean that individuals seeking diagnosis may not have access to professionals with the breadth of knowledge of co-occurring needs and at best, may experience sequential long waits on different diagnostic waiting lists.

NHS resources are stretched. Waiting times for diagnosis are often long and (along with access to diagnosis) are a stated priority for the UK government. Professionals and stakeholder groups have expressed concerns over the ability to follow diagnostic guidance due to limited resources (NICE autism guidance surveillance 2021). In response to both the complexity of diagnosis in neurodevelopment and the impact of long waiting times on neurodivergent people and their families, many are calling for multi-diagnosis assessment pathways or neurodevelopmental pathways (e.g. Male, Farr & Reddy 2021; Rutherford et al. 2021; Rutherford & Johnson 2022; see also Embracing Complexity in Diagnosis (Embracing Complexity 2019).

Excerpt from Rutherford, M., & Johnston, L. (2022):

“There is clear evidence that different neurodevelopmental conditions defined as they are currently, usually co-occur and overlap and it is often the combination of individual profile or “neurotype” together with the environment, that determines support needs rather than diagnosis. One consequence of this development in diagnostic criteria, is that it supports the shift in clinical practice, away from a “single condition” focus towards “neurodevelopmental” pathways and a diversification of our approach to assessment, diagnosis, and intervention.”

Following the publication of the NHS Long Term Plan (2019), NHS England provided funding to trial a variety of new approaches to diagnosis across the region producing a National Framework in April 2023 (see National framework and operational guidance for autism assessment services, NHS England 2023). England has also introduced the NHS Right to Choose legislation (see Your choices in the NHS (NHS 2023). Scotland, through the National Autism Implementation team (NAIT), recommend a shift towards a single neurodevelopmental pathway to diagnosis with progress being made e.g. some areas are currently testing new models aiming to roll out new neurodevelopmental diagnostic pathways in 2023.

See resources section for further reading.

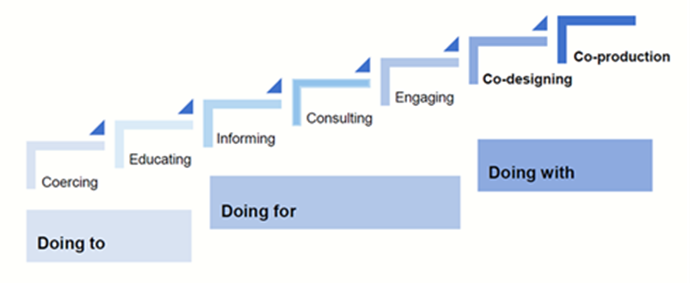

Collaborative practice and co-production

Accounting for the nature of autism, prevalence of associated diagnoses and impact, a range of professionals and services will be variably involved with an autistic person over the course of their life. Working in partnership with others across all levels is central to improving outcomes for autistic people. This includes co-production with those with lived experience of autism, parents/carers of autistic children and adults, and collaboration with the many other organisations (see resources section) and professional groups involved in supporting autistic people when developing services and conducting research. Involvement of autistic people has been historically lacking in these areas but with emerging progress and calls for change (e.g. Pukki et al 2022). Partnership working with autistic individuals and others includes understanding and respecting different perspectives, aiming for shared views and goals. We highlight the autistic parent/carer and neurodivergent co-workers, provide a list of key professionals and any associated published national guidance in the Resources section, and share information on supporting informed choice through Shared Decision Making and on co-production principles.

The autistic or neurodivergent parent

A significant proportion of speech and language therapists (SLTs) will work alongside parents in support of their child. Whilst the recommendations below can apply to all parents, we draw attention to the autistic parent.

With heritability of autism estimated to be between 50-96% (Colvert, Tick & McEwen 2015; Sandin et al 2014; Bai, et al 2019), we can anticipate that many parents of autistic children are autistic themselves. Some may have been diagnosed in adulthood, some may self-identify as neurodivergent and with some only recognising this in themselves as their own child receives a diagnosis. Other parents may have other related neurodevelopmental diagnoses such as ADHD.

Research into the experiences of autistic parents is limited but emerging. Autistic parents form close connections with their children, love them and their shared autistic experience enhances these bonds (Smit & Hopper 2022). However autistic parents can experience challenges when interacting with health, education and social care professionals in pursuing support for their child. They indicate that this is due to professionals lacking knowledge of autism, the proliferation of stereotypes and incorrect assumptions about their parenting capabilities (Pohl et al. 2020; Fletcher-Randle 2022; Smit & Hopper 2022). These negative assumptions and stigma, along with a concern that parent blame for all parents has become institutionalised in social care services in England when parents seek support (see Institutionalising parent carer blame – Cerebra (2021), sources of stress are not inconsiderable for autistic parents.

SLTs should:

- recognise that some carers may be neurodivergent and so these recommendations may also apply.

- be sensitive to parent communication and interaction styles, making adjustments to their own style as needed including using clear and direct language, irrespective of parental disclosure of their neurodivergence.

- acknowledge that there is diversity in parenting styles and accept that autistic parenting is equally valid.

- be aware that autistic parents may be parenting through a lens of historical trauma and that interacting with professionals can be a source of additional stress.

- establish a trauma-informed, trusting and collaborative relationship with a parent.

- personalise support to the unique needs of the child and the family, including signposting for parent support.

- sensitively discuss with autistic parents/carers their preferences and ability to engage with one-size-fits-all pathways such as online workshops and parenting groups to ensure equal access to support and information.

- be aware of any unconscious bias towards parents/carers from less heard groups and those who are neurodivergent to avoid holding parents/carers responsible for the difficulties their child is facing.

The autistic or neurodivergent colleague

See RCSLT guidance on Supporting SLTs with disabilities in the workplace.

SLTs will work alongside colleagues who are neurodivergent, who may or may not have a formal diagnosis or have shared any diagnosis. We value the strengths and creativity a neurodiverse workforce brings. We commit to actively supporting and promoting neuro-affirmative collaborative practice with our colleagues. This will include accommodating for differences in communication and interaction styles, preferences and values and making reasonable adjustments through the employment process from job application, interview and to being in the workplace. Neurodiversity passports for staff may be beneficial. We note that the government has released a new review to boost the employment and retention of autistic people, see New review to boost employment prospects of autistic people Department for Work and Pensions 2023

For further viewpoints and resources see our resources section.

Key professionals

When working with other professionals, consider the potentially different theoretical and philosophical basis of their training, for example when trained from a mental health or an educational perspective rather than a developmental one. Their philosophy and approach to understanding autism and neurodiversity may also differ, which can result in differences in recommendations, for example in Education Health Care Plans in England or Co-ordinated Support Plans in Scotland. There are advantages to be gained by considering different viewpoints and we reiterate placing the autistic person at the centre in resolving any differences. Professional input will be contextualised based on their training and experience. See resources section for examples of professional guidance from these groups.

- Allied Health Professionals e.g. occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dieticians

- education professionals e.g. teachers, teaching assistants, educational psychologists

- medical professionals e.g. paediatricians, General Practitioners (GPs), nurses

- mental health professionals e.g. psychiatrists, psychological professionals, mental health nurses/practitioners and counsellors

- social care professionals e.g. social workers, care workers

Shared decision making (SDM)

“Shared decision making is a joint process in which a healthcare professional works together with a person to reach a decision about care” NICE 2021 (‘Care’ includes, for example, a decision to engage in speech and language therapy, or access or participate in a diagnostic assessment. For training on SDM see Shared Decision Making – elearning for healthcare.

Best interest decisions are made when an adult is judged not to have mental capacity for a specific decision (See NICE Guidance on Decision-making and mental capacity and RCSLT Guidance on Supported decision making and mental capacity). People over the age of 16 who do not have capacity (see Mental Capacity Act 2005) are supported to be as involved as possible in decision making (see RCSLT learning disabilities guidance). SLTs have a role in supporting reasonable adjustments for any language and communication factors that may be a barrier to decision making for a person over the age of 16 ( see role of SLT: intervention and support).

For consent to treatment in children please see: Consent to treatment – Children and young people (NHS 2022).

Co-production principles

Co-production is increasing, particularly in the areas of service development and research; however, there were limited examples of co-production in developing guidance. We provide a copy of the co-production principles that were agreed by the working group for this guideline. These principles were based on various resources which can be found in our resources section.

Role of the SLT: Introduction

Speech and language therapists (SLTs), irrespective of role, will encounter autistic or neurodivergent individuals during their working life. We have the opportunity to contribute to improved outcomes for this group by maintaining an up to date understanding of autism and other associated neurodevelopmental diagnoses, a commitment to neurodiversity affirming practice and in how we intervene, support and advocate for autistic people and their families both in clinical practice and in research.

The focus of our influence includes, and is not limited to, the following areas: language, processing, social communication/interaction, eating and drinking; contributing to understanding and managing distress and mental wellbeing, as well as the impact of sensory processing differences, empowering the individual and supporting self-advocacy, assist in developing safe and consenting and meaningful relationships, helping autistic people understand their own autistic experience, addressing functional impacts across environments, empowering others in the support of the individual, leadership and advocacy across and within systems such as health, education, social care, the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sector and in research.

At the centre of our practice, and a requirement for our professional registration, is a commitment to evidence-based practice (EBP); the integration of service user preferences and values, best research evidence and clinical expertise. This requires an SLT to think critically about all sources of information and how it meets the needs and preferences of an autistic person and their family. For further information see RCSLT research pages and EBP resources.

Our role with autistic people can overlap and complement the roles of other professionals. RCSLT guidance in multiple areas are relevant and there is a wealth of published information, resources and national recommendations to support autistic people including those written by autistic people and their parents. We refer to national guidance across the UK and welcome the resources developed such as those by The National Autism Implementation Team in Scotland, The National Autism Team in Wales and by NHS England. This guidance will therefore signpost rather than repeat when relevant.

Role of the SLT: Assessment and diagnosis

Accessing Speech and Language Therapy

To ensure equal and ongoing access to speech and language therapy and to minimise risks of inappropriate and untimely discharge (See Doherty et al 2022):

- Speech and language therapy services should ensure that referral procedures are sufficiently flexible to accommodate different communication and interaction preferences.

- Initial appointments with a family and/or service user include a discussion about reasonable adjustments necessary to facilitate ongoing support.

Recognition

Speech and Language therapists (SLTs) should:

- have knowledge of the relevant features of autism, including sensory differences, and how they can differ at different ages (See Definitions section).

- have knowledge or awareness of the features of at least the main co-occurring diagnoses, including mental health, to encourage holistic thinking from the outset and ensure onward referrals are appropriate, including when diagnostic pathways are diagnosis-specific e.g. for autism only or ADHD only (Se Co-occuring diagnoses)

- be aware that features of autism should be taken in the context of a person’s overall development and conscious of the risk of features being undetected in people with a learning disability, or in those who are verbal communicators.

- recognise that autistic people may camouflage, mask or compensate for their differences in certain situations but may be more comfortable expressing their autistic self in the home context; information from significant others such as parents or partners should be valued (with assent/consent as required). (See Definitions)

- be aware of the different behavioural expressions of autism and the risks of cultural and gender bias and the risk of under-recognition of autism in individuals assigned female at birth. This bias also has implications when seeking information from, for example, education settings when undertaking diagnostic assessments (see for example Whitlock et al 2020). (See Definitions)

- be sensitive to the cultural context of the autistic individual and their family, listening and respecting their views as experts on their own culture.

- ensure that a full explanation is given to the individual and/or their parent/carer to ensure consent is informed when making onward referrals for diagnostic assessment or for other intervention or support. This should include referencing the diagnostic label and the reasoning behind the concern.

- be aware of, and respond to, the equality, diversity and inclusion agenda and how it can mitigate health inequalities in under-served groups. Recognise the impact of intersectionality and associated additional risks of marginalisation (see RCSLT Diversity, Inclusion and anti-racism: resources, guidance and updates)

Assessment

Please refer to RCSLT information on assessment. In addition, we highlight the following:

- The aims of an assessment should be clear, the approach holistic, integrating information from a variety of sources such as objective clinical observations, standardised and non-standardised assessment (being aware of their strengths and limitations), information from others known to the individual including other professionals and, when possible, seeking the views and perceptions of the person being assessed. SLTs should not rule out further observation when their own observations do not confirm parents or carers concerns.

- Assessment should include an understanding of a person’s support network and environment. It should consider how these might contribute to, or support, a person’s current needs and identify opportunities for change to improve or enhance outcomes for the individual, identifying reasonable adjustments.

- Consider the ways in which a person’s language, communication, social cognitive, sensory needs, and the impact of the environment contribute to a person’s emotional regulation and distressed actions and responses if present.

- When carrying out observations in natural contexts, SLTs should recognise the potential effect and impact on a person if they are aware or notice that they are being observed, both when their agreement has been obtained and not.

- SLTs should be aware of the contribution of their own and others interaction styles during natural interactions and observations, taking account of the Double Empathy Problem (See Setting the scene: Neurodiversity and the Neurodiversity Movement).

- Conclusions following assessment should be informed by the best available evidence and clinical judgement, recognising the fallibility of such judgements.

Diagnosis and clinical formulation

With communication differences being core to autism, and the known contribution of such differences to a person’s mental wellbeing, their education and life chances, SLTs form a vital part of a diagnostic team and in contributing to clinical formulation. The impact and nature of language and communication differences are broad, with associated co-occurring diagnoses contributing. Examples of the variation in presentations include those who may have fluent language but experience subtle differences in pragmatic skills, with others who use few words and/or have difficulty understanding language.

Across the UK diagnostic assessments vary in how they are delivered and coordinated (See Neurodevelopmental Pathways to Diagnosis). SLTs may be involved in all or some stages of the process including before and after the diagnostic assessment. Within the assessment itself, SLTs may focus on completing assessments with the individual but in some services may be responsible for taking an autism specific developmental history from significant others. In some areas, SLTs are not directly involved but may provide a written report about an individual’s language and communication profile and interaction style. SLTs, along with the rest of the multidisciplinary team, should approach the assessment process collaboratively with the individual and their family, recognising that the diagnostic process itself can be therapeutic when managed well, including when the outcome is no diagnosis.

- The RCSLT, in keeping with national autism guidance across the nations, advocates for the direct involvement of speech and language therapy in diagnostic assessments.

- When speech and language therapy is not involved directly in diagnostic assessment we would encourage SLTs to be aware of the following recommendations, to ensure that written contributions support the diagnostic process.

Knowledge

SLTs should be:

- aware of the strengths, limitations and current perspectives of psychological theories of autism, cognition and language, examples include central coherence theory, double empathy problem, executive functioning, gestalt language processing, monotropism, sensory processing accounts, theory of mind.

- aware of transdiagnostic traits (traits or experiences that occur across many overlapping neurodevelopmental diagnoses) such as alexithymia, executive function, intolerance of uncertainty.

- recognise the centrality to understanding and supporting autism that many autistic adults place on the double empathy problem, monotropism, sensory processing and the impact of masking (see resources page).

- familiar with published autism guidelines across the UK Nations and national drivers.

- conversant with the DSM-5 and ICD-11 diagnostic criteria of at least the main co-occurring diagnoses (ESSENCE) (See Co-occurring Diagnoses & Differential Diagnosis) and any related published guidance (e.g. RCSLT, NICE, SIGN) for those diagnoses.

- familiar with common language, communication and interaction presentations and impact related to the main co-occurring diagnoses e.g. in ADHD (see e.g. Geurts and Embrechts 2008, Gooch et al 2019), in learning disability (see RCSLT learning disabilities guidance).

- trained in the use of assessments if relevant to their specific role e.g. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule 2nd Edition (ADOS-2), Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO).

- familiar with assessments typically completed by other professionals and understand how they relate to an individual’s language and communication abilities e.g. assessments of cognition (e.g. Wechsler Intelligence Scales: WPPSI – preschool & primary, WISC- children WAIS -adults, adaptive functioning (e.g. Adaptive Behaviour Assessment System ABAS; Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales VABS), motor abilities (e.g. Movement Assessment Battery for Children – Movement ABC), visual and sensory processing (e.g. The Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration – Beery-VMI).

Role in diagnosis

SLTs should:

- contribute to diagnostic formulation and understanding of the person as a whole e.g. the impact of communication on risk, and recommendations for reasonable adjustments.

- communicate with sensitivity, using language matched to the language needs, style and preference of the individual and their family about the process, what to expect and giving feedback. There may be occasions where support is offered to other professionals to achieve this.

- assess and identify language, social communication and interaction differences and their impact.

- recognise the strengths and limitations of diagnostic tools (see Bishop, and Lord, 2023).

- recognise dysfluency and speech sound difficulties and their impact.

- contribute to assessment and observation of learning abilities, sensory preferences and mental health and of how a person acts and responds in different situations.

- consider a differential diagnosis of Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) (see RCSLT DLD guidance).

- consider if Language Disorder is a co-occurring diagnosis (see Co-occurring DLD or Language Disorder Associated with…? (Archibald 2021)

- share with the assessment team the potential contribution these differences may have on other aspects of assessment and on the difficulties the individual is experiencing.

Role of the SLT: Intervention and support

Principles of neurodiversity-informed intervention and support for autism

- Interventions and outcomes are an agreed choice and priority of the autistic individual and/or their parent/carer/advocate.

- Successful communication and interaction are a responsibility shared by everyone, including the autistic person and everyone in their environment but recognising inherent power and possible capacity imbalances for example between autistic people and professionals. Speech and language therapists (SLTs) have a role supporting communication and interaction changes and adaptations in all relevant people, without undue expectations on autistic individuals.

- SLTs have a responsibility to openly discuss options for support and intervention with autistic people and their parents or carers where appropriate. Parents and carers may also seek advice from SLTs about interventions which are not a core part of practice or solely the responsibility of an SLT. These balanced discussions should include advantages, disadvantages and current thinking on particular approaches to ensure that choice is well informed.

- SLTs should be aware that the research evidence for any intervention currently remains limited.

Interventions:

- focus on harnessing a person’s strengths, interests and abilities.

- aim to provide support and adaptations that affirm an individual’s neurodivergent identity.

- are personalised to the needs of that autistic person at that time: no single approach is recommended for all autistic people all the time.

- are evidence-based (triangulating best scientific evidence, clinical experience and the person’s values). SLTs should be aware that if deviating from a manual or modifying the delivery or prescribed dosage of a named intervention with proven efficacy, assumptions of efficacy should be confirmed and effectiveness monitored.

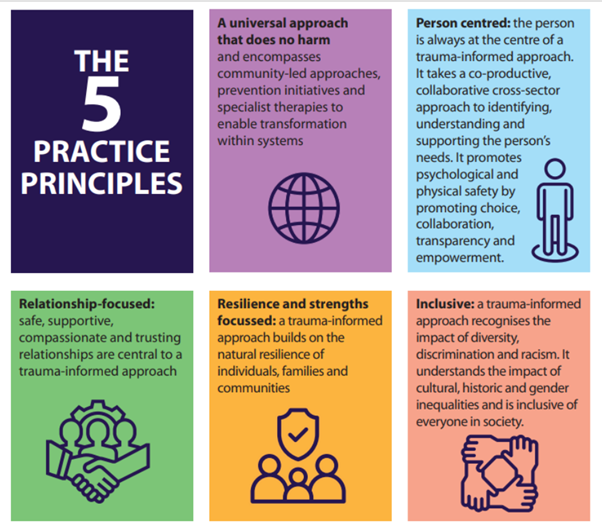

- are trauma-informed. This includes recognising the potential impact of multiple and serial stress reactions that may result in autistic trauma, for example in response to cumulative changes in routine, social situations, or sensory stimuli, and taking account of any Adverse Childhood Events (ACE’s). Support should be personalised to avoid risk of re-traumatisation using the following principles in Figure 3.

Areas of Intervention and support

When considering any specific intervention or support, SLTs are required to use evidence-based practice (EBP). This starts with the needs and preferences of the autistic person and/or/with their parents/carers/advocates. It includes consulting National Guidelines for their recommendations, including any approaches that are specifically not recommended, and taking a critically evaluative approach to research and any other sources of data or information, including this guidance. This is integrated with an SLT’s clinical knowledge and experience with an ability to recognise when a particular situation requires them to seek further advice. Choice of intervention and/or support should be highly individualised, developmentally relevant, considerate and proportionate.

SLTs should be aware of the implications of poor practice or inaccurate adherence to an intervention’s guideline or protocol, especially when making recommendations to untrained others to deliver such an approach for a service user.

1. Language interventions should:

- support opportunities to facilitate the development of all aspects of structural language, particularly in children (e.g. receptive, expressive, vocabulary, syntax, narrative)

- ensure that the choice of language goals is meaningful to the autistic person e.g. vocabulary related to their current interests and necessary to be able to meet their functional needs.

- consider the use of Alternative Augmentative Communication (see RCSLT AAC guidance) e.g. objects of reference, manual signs, paper based and electronic systems including apps.

2. Social communication and understanding interventions include:

- supporting an autistic person to have a functional and meaningful way of, communicating their needs, sharing their interests, developing friendships and being able to self-advocate relevant to different environments. Self-advocacy involves learning about oneself, your needs and being confident and able to communicate this with others in the right situation at the right time e.g. attending doctor’s appointments, job interviews. For some, this refers to being able to communicate their basic needs and to use their own Communication or Hospital Passport (see e.g. Personal Communication Passports (CALL 2023), My Healthcare Passport (East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust 2014) and Talking Mats). Recognise that communication needs will vary, such as between home, school, college and work.

- supporting Autistic people who may want to engage in social understanding work and/or request assistance in managing and navigating particular social situations – both in anticipation of planned social interactions and reflecting on past social experiences. This should be supported using a highly personalised and individual approach. When facilitating their understanding, ensure that outcomes support self-advocacy. Techniques such as Comic Strip Conversations™ and Social Stories™ may be helpful in supporting people to break down a social situation and consider the contribution of the language, thoughts and feelings of all the participants in an interaction and understanding of the double empathy problem. See also Respecting Neurodiversity by Helping Social Learners Meet Their Personal Goals (Crooke and Winner 2022).

- supporting culturally sensitive training or coaching neurotypical people in autistic communication styles. This is recommended and includes supporting non-autistic people to recognise their own bias in interacting with autistic people (Sasson et al 2017), and/or facilitating a self-prompt approach (see Silver & Parsons 2015 and 2022). For key persons working with autistic children and adults, consider other interaction approaches such as Intensive Interaction (Hutchinson & Bodicoat 2015); some parent-child interaction approaches have also been used with other key persons such as education professionals instead of the parent, and with adults instead of children.

3. Parent/carer mediated interventions

Coaching parents/carers in the delivery of an intervention has a number of advantages including creating a highly personalised approach and supporting generalisation into the natural environment of the home setting. Across all types of parent/carer mediated interventions, there is supporting evidence suggesting the positive benefits to an autistic child or adolescent’s subsequent ability to manage in everyday life (e.g. Conrad et al. 2021). For SLTs, parent/carer mediated interventions include:

- parent-child interaction (PCI) approaches such as Paediatric Autism Communication Therapy (PACT) (Green et al 2010; Pickles et al 2016) and More Than Words® (e.g. Carter et al 2011). These approaches take a developmental approach to provide the optimum environment for the foundations of language, communication and interaction to develop and flourish. They aim to enhance the parent’s understanding of their child’s language, communication and interaction style and provide guidance on how parents can modify their own communication and interaction to foster, and build on their child’s abilities. Other PCI approaches are also used in non-autistic populations e.g. for dysfluency, where again the focus is on changing parent style and the environment not the child.

- consider the family’s current capacity to take on extra demands related to such interventions and offer alternatives if appropriate.

4. Distressed behaviour and emotional regulation

SLTs have a role in identifying and ameliorating communicative and environmental factors, including understanding sensory components, that may contribute to an autistic child or adult reacting or acting in ways that are suggestive of distress, for example, by hurting themselves or others; running away; damaging property, or ruminating on their understanding of social relationships and interactions. This includes understanding how these actions and reactions may relate to unmet needs, an autistic person’s preferences and what the person is trying to communicate through their actions and modifying the contributors to that distress. These could be environmental factors, or an expectation that has not been well communicated to them, or that their initial communicative attempt was missed, not recognised or misunderstood, or when an individual does not have an alternative way of communicating this need. Note that a physical health problem should be ruled out first, particularly when the occurrence or degree of distress is novel.

Actions and reactions indicative of distress can be viewed in a negative way by those they affect, particularly if they are directed to, or cause harm to another person. This can often result in a breakdown in the relationship between the autistic person and those around them, risking the loss of friendships or supportive relationships. An important part of ensuring these relationships can be repaired is to support both parties in understanding the differing perspectives on the situation, including the autistic person’s point of view. This includes encouraging them to reflect on why differences in communication or understanding resulted in the communication breakdown rather than viewing the person’s actions as wilful defiance or destruction. Likewise, and when possible, it includes supporting the autistic person to understand the impact they may have had on the other person. This has the potential to empower them to repair their relationship and resolve any uncertainty they may experience as to why the other person has continued to be annoyed or distant once the situation has passed.

Public perception of distressed behaviours can be negative. If the person’s differences and support needs are not understood by the person who is observing the behaviours then there is a possibility that these will be viewed as criminal acts, particularly when they have caused damage to public property or harm to another person. In children, the impacts of distressed behaviour can include school exclusions and emotional based school refusal or social service involvement. Where any system (e.g. Education, Social Care or Criminal Justice system) becomes involved following distressed behaviours, SLTs have an important role in ensuring that the system understands the autistic person’s communication differences and how these have impacted on the situation.

SLTs should:

- support the person’s ability to communicate their needs safely and self-advocate. This may include teaching an alternative way to express a particular need or make a request.

- support an autistic person to recognise and identify their emotional state to support their ability to communicate and self-advocate. Support significant others to recognise how an autistic individual expresses their emotional state.

- ensure that the social and physical environment meets the needs of the autistic person through making reasonable adjustments (see below).

- if relevant to the SLT’s area of practice, contribute towards a person-centred assessment aimed at understanding the reasons contributing to a person acting and reacting in such ways and identifying a support plan focused on environmental changes and communicative support (for those with a learning disability, many services use Positive Behaviour Support). The assessment should minimally include:

- an understanding of the contributions of the physical, social and sensory environment.

- a consideration of the impact of a person’s environmental experiences both immediately before, after and if necessary for a longer period leading up to the autistic child/adult’s response.

- an understanding of how the autistic child/adult communicates and are understood by others, and if this is meeting their needs.

- ensuring that they are not unwell or in pain.

- provide support for all parties involved to understand the communication breakdown and reflect on the situation once the autistic person has identified that they are ready to. Consider using structured tools such as Comic Strip Conversations™ to support relationship repair.

- provide support to prevent communication breakdown during contact (of any kind) with the justice system. Where possible support the autistic person’s understanding of the criminal justice system and relevant sections in the mental health act.

- support systems to understand the contribution of communication differences when distressed behaviour or social communication results in significant impacts, for example in the criminal justice system when it is viewed or interpreted as criminal (see RCSLT guidance on Justice) or in education before it results in exclusions. This includes advising on reasonable adjustments and how this relates to vulnerabilities.

- to be conscious of both unexpressed mental health needs and service users’ vulnerability.

For further information see our resources section.

5. Environmental supports & reasonable adjustments

SLTs can contribute to identifying necessary environmental adaptations and reasonable adjustments, advocating for a neurodiversity affirming environment. This includes the use of visual supports (objects, photos, pictures, the written word), managing the sensory environment, making the environment predictable and reliable and ensuring others understand the communication needs of the autistic person including making adjustments to their own use of language and interaction style.

For further information see our resources section.

6. Teaching strategies

Neuro-affirmative interventions aim to improve subjective quality of life and support the developmental trajectory of an autistic person even if that trajectory is limited for example by co-occurring diagnoses. To achieve this, there will be situations where specific skills or strategies will need to be taught and/or when an autistic person may actively request to learn a strategy even when it is not an area of strength. For example, teaching strategies that support an autistic person to meet their own basic needs such as communicating what they want (with many settings utilising the Picture Exchange Communication System** (Bondy & Frost 1994; Preston & Carter 2009)), to say no, to be able to leave, to ask for the toilet (e.g. using AAC) or specific social skills (see Social Communication and understanding section) such as interview skills or attending doctor’s appointments. We acknowledge that some autistic people hold the view that neurotypical communication shouldn’t be taught but others also say that knowing social norms is empowering.

SLTs should consider teaching specific language and communication skills:

- when an autistic person asks them to.

- when the parent/carer of an autistic child asks, ensuring the child and young person is involved in the decision making.

- when it is in the autistic person’s best interest following a ‘Mental Capacity Assessment’, enhances quality of life and/or reduces risk.

*Critical discussion related to some interventions*

We reference such interventions to ensure that SLTs are informed both to support their own critical thinking in evidence-based practice and in supporting shared decision making with autistic people and their parents or carers, including when a ‘Best interest’ decision is required. The neurodiversity movement considers these approaches to be ableist and there is strong disagreement with behavioural interventions that aim to change a person’s behaviour through compliance training. This list is not exhaustive. It also does not include other examples of ableist practice that may be seen such as posters in schools illustrating a neurotypical description of how children can show they are listening. We acknowledge that not all agree and some autistic people and/or their parents choose these approaches. None of the following are exclusive to speech and language therapy.

Behavioural Approaches:

- Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) is focused on behaviour change using the principles of operant conditioning based on B F Skinners learning theory work. Current approaches emphasise positive reinforcement rather than negative reinforcement. It is a widely used outside of the autism field e.g. in weight loss programmes and in business (organisational behaviour development). In autism, the approach is used intensively (30-40 hours per week) e.g. in Early Intensive Behaviour Interventions (EIBI’s). Lead practitioners are certified and it is not specific to a particular professional group.